The Christian Science Hymnal: History, Heritage, Healing

The Christian Science Hymnal: History, Heritage, Healing

The Christian Science Hymnal: History, Heritage, Healing

Listen to this article

Chapter 3

The Hymnal takes hold, 1892

The December 1892 issue of The Christian Science Journal proclaimed to readers that the Christian Science church had its own official songbook:

The long-looked-for Christian Science Hymnal has at last appeared. It will be welcomed heartily by the field. It is a selection of Spiritual Songs adapted to the use of Christian Science churches, Sabbath Schools, and other meetings. In point of mechanical make up it will bear favorable comparison with similar books of the various denominations; and as to the hymns, they are of the highest order. Some of them are original; others are selected.1

The 1892 Christian Science Hymnal.

Click to view the pages of this interactive digital book.

A question of theology

It is important to remember how revolutionary Mary Baker Eddy’s thought was about the spiritual nature of man and woman. The 1892 Christian Science Hymnal contains textual material indicative of an orthodox theology—from which the young church’s hymnody was slowly departing but at that point still embraced to some degree. The preface acknowledged this:

In presenting this Hymnal for the use of Christian Scientists the Committee do not claim that it is strictly scientific, as they were obliged to select very largely from hymns composed by those who were unacquainted with the teachings of Christian Science.

While not entirely composed of hymns written exactly in accordance with the doctrines of Christian Science it presents the acme of religious and poetic thought contained in the best hymns of the day, as well as in the best compositions thus far contributed by Christian Scientists.2

For example, the following hymns from the 1892 edition contain descriptions that would most likely not be published today:

Hymn 159:

From out the hideous night, …

Ambushed on ev’ry side,

Dark error’s foemen hide…

Hymn 191:

Upon the dark mountains they stumble,

They are bruised on the rocks and they lie

With white pleading faces turn’d upward,

To the clouds and the pitiful sky.3

In contrast, Hymn 39 included the 1696 versification of the ninety-first Psalm by Tate and Brady,4 with words more representative of the Christian Science perspective:

Hymn 39

He that has God his guardian made,

Shall under the Almighty’s shade

Secure and undisturbed abide;

Thus to myself of Him I’ll say,

He is my fortress and my stay,

My God, in whom I will confide.5

Eddy later wrote that the ninety-first Psalm “contains more practical theological and pathological truth than any other collection of the same number of words in human language except the Sermon on the Mount of the great Galilean and hill-side Teacher.”6 Set to the tune BERA by the American musician John E. Gould (1821–1875), this music and its revised text have remained a favorite with Christian Science congregations.

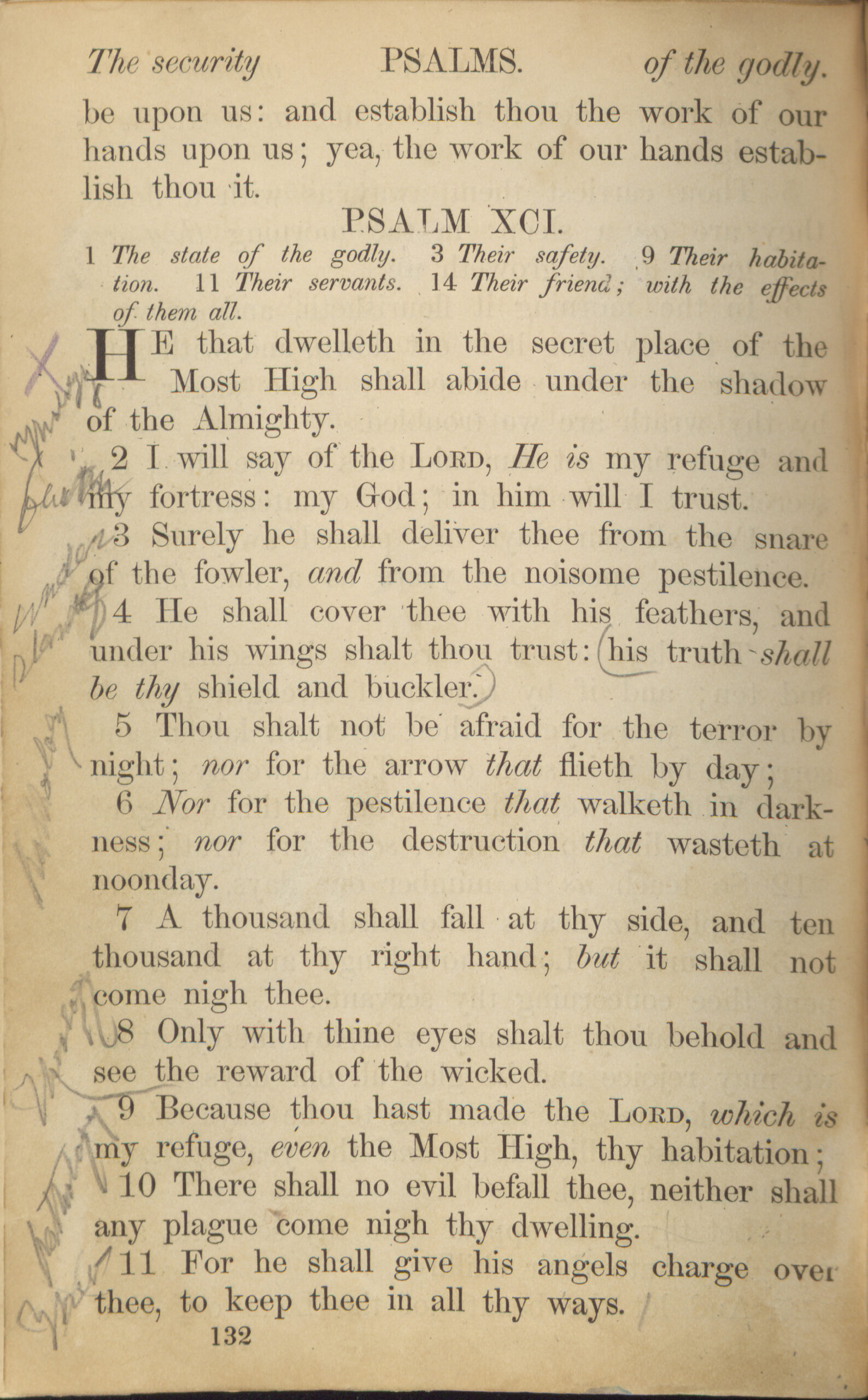

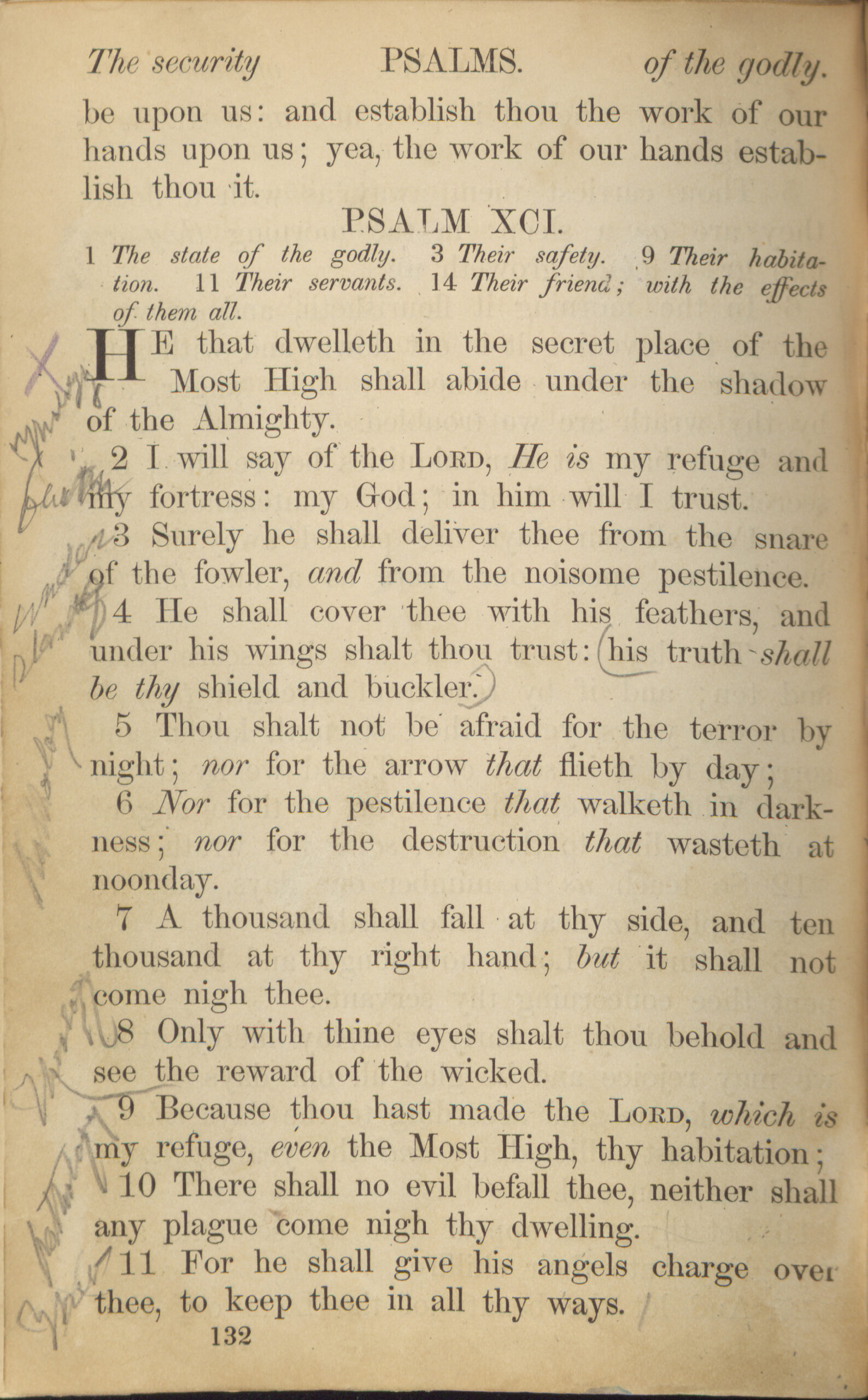

Mary Baker Eddy’s marginal notes for Psalm 91, written in her copy of The Book of Psalms: translated out of the original Hebrew; and with the former translations diligently compared and revised, 1879. B00016.

Eddy later wrote that the ninety-first Psalm “contains more practical theological and pathological truth than any other collection of the same number of words in human language except the Sermon on the Mount of the great Galilean and hill-side Teacher.”7 Set to the tune BERA by the American musician John E. Gould (1821–1875), this music and its revised text have remained a favorite with Christian Science congregations.

Mary Baker Eddy’s marginal notes for Psalm 91, written in her copy of The Book of Psalms: translated out of the original Hebrew; and with the former translations diligently compared and revised, 1879. B00016.

Photo of Mary Alice Dayton, circa 1893. Gendron Artistic Photographer. Courtesy of Longyear Museum.

Christian Scientists contribute

The same Journal issue that heralded the new hymnal also included the article “A Word of Thanksgiving for the Christian Science Hymnal” by Alice Dayton.8 “The long expected Hymnal is at last completed,–” she wrote, “a neat book, harmonious in type, binding, variety of tune, and, best of all, with words which voice a more scientific thought than any hymn-book tried heretofore; and consequently is better adapted to the use of [Christian] Scientists.”9

Dayton was an example of the Christian Science poets who emerged during this period. A member of Eddy’s February 25–March 5 Primary class in 1889, she became a Christian Science practitioner in 1891 and later began teaching the religion in 1922. Her poem “Potter and Clay” first appeared in the September 1890 Journal. Based on Jeremiah 18:2–6, it was the result of an appeal from the Journal’s editor for submissions from those “educated rightly” in Christian Science. In a note preceding her poem, Dayton stated, “The following grew out of a suggestion that Science should by this time bring forth words for its own Hymnal.” She went on to say that “it is offered without any attempt at self-justification, or maternal pride.”10

“Eternal Mind the Potter is” (Tune by I. Pleyel, Hymn 92)

The Preface to the 1892 Hymnal also explains the arrangement of texts and tunes. It recognizes the significant contributions of editor Lyman Brackett:

Much labor has been bestowed upon this compilation, by the Committee and, in the musical department of this work, great credit is due Mr. Lyman Brackett of Boston, Mass., for untiring effort to present the most useful and varied collection of tunes ever issued in one hymnal,– the purpose being to appeal to every lover of church music, of whatever taste or ability.11

Musical improvements

As committee members worked on the new hymnal, one of their main goals was to raise the quality of the music included, while retaining tunes familiar to most churchgoers. They incorporated a number of selections from famous classical German and Austrian composers, including Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Mendelssohn. The hymnal also contained melodies from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century psalters and chorale books.

In addition, approximately 50 of the best hymns from the Social Hymn and Tune Book12 were included. Two notable examples were Isaac Watts’s 1718 work “From all that dwell below the skies,” set to the tune OLD HUNDREDTH, and Anna L. Waring’s 1850 poem “In heavenly love abiding,” set to Alexander Ewing’s eponymous tune. The elevated musical caliber and strength of all these sources did much to usher quality music into the 1892 edition, and to lift hymn singing to a higher spiritual, cultural, and intellectual level.13

In addition, the works of a number of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English and American composers and church musicians were added. Representatives of the English tradition included luminaries such as Arthur Sullivan (“Onward, Christian soldiers”), John B. Dykes (“Lead, kindly Light”), William Hoyte (“‘Feed my Sheep’”), and William H. Monk (“Abide with me”). American musicians were represented by Lowell Mason (“A glorious day is dawning”) and John E. Gould (“He that hath God his guardian made”).14

Committee members must have felt that it was important to incorporate tunes that reflected the musical taste of the day. Brackett composed alternative melodies to most of the hymn texts in this first edition—99 in all. This was no small accomplishment, given the fact that he was responsible for selecting virtually the entire compilation of tunes and arranging them into the plan. Only 30 of these tunes were included in the next Hymnal edition, published in 1910. Brackett’s settings probably found a measure of favor and acceptance difficult to appreciate today; his musical style eventually passed out of fashion. A further-reduced number were included in a revised 1898 Hymnal, and all but five of his compositions were dropped from the 1932 edition.15

The versatility of text and tune

The 1892 edition contained 210 hymn texts. Of these, 177 were printed with three alternative tunes. This was similar to the arrangement found in the Social Hymn and Tune Book, with the first tune being the most familiar. Typically the second tune was composed primarily by English or German musicians, such as those already mentioned, with Brackett composing the third tune. Hymns 178 through 193—some of which were designated for Sunday School use—were set to only one tune. Hymns 194 through 210 were alternative arrangements of texts and tunes appearing earlier in the Hymnal, intended for male-voice quartets (with mixed-voice options).

Video: Learn how the words and music of a hymn fit together.

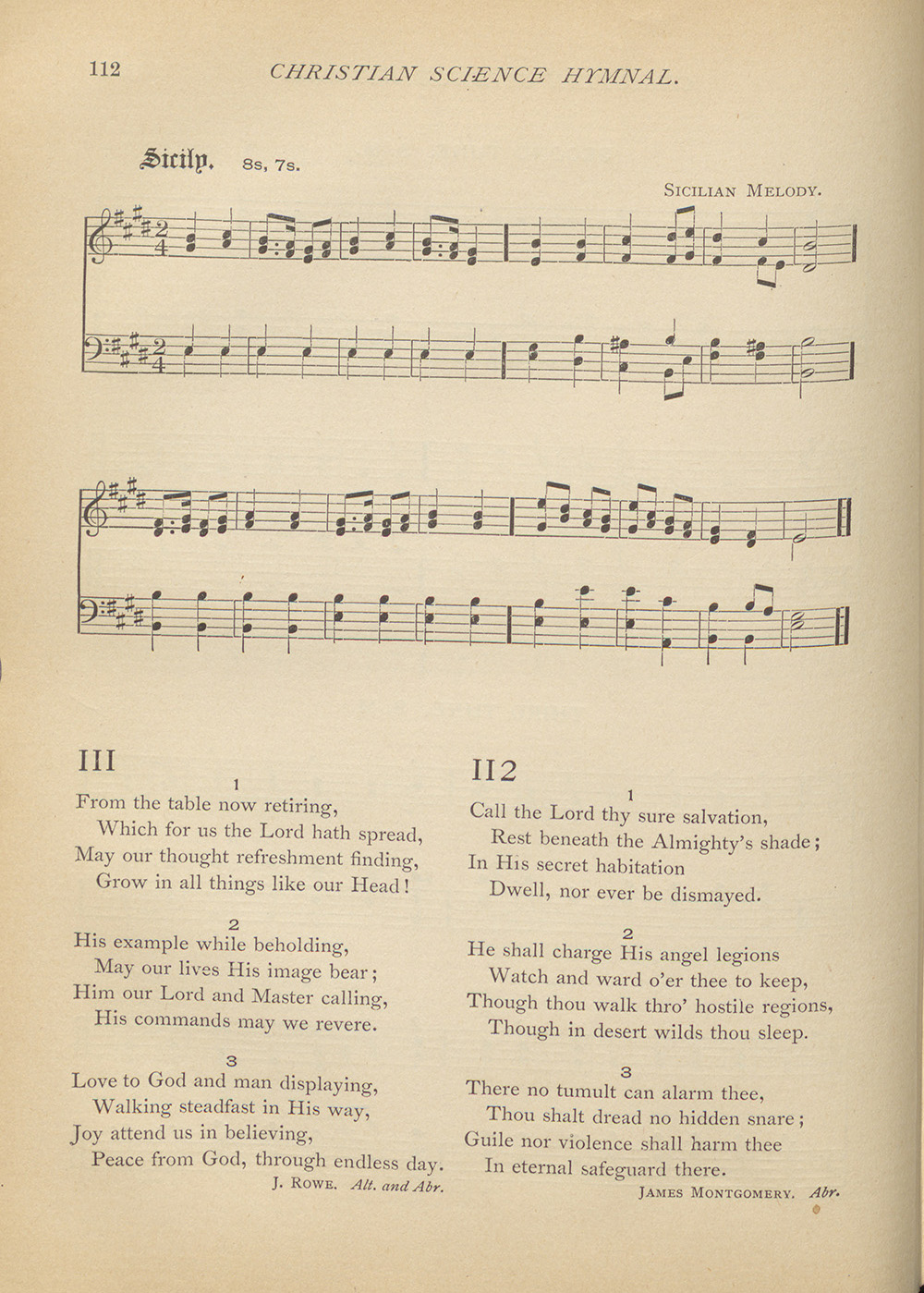

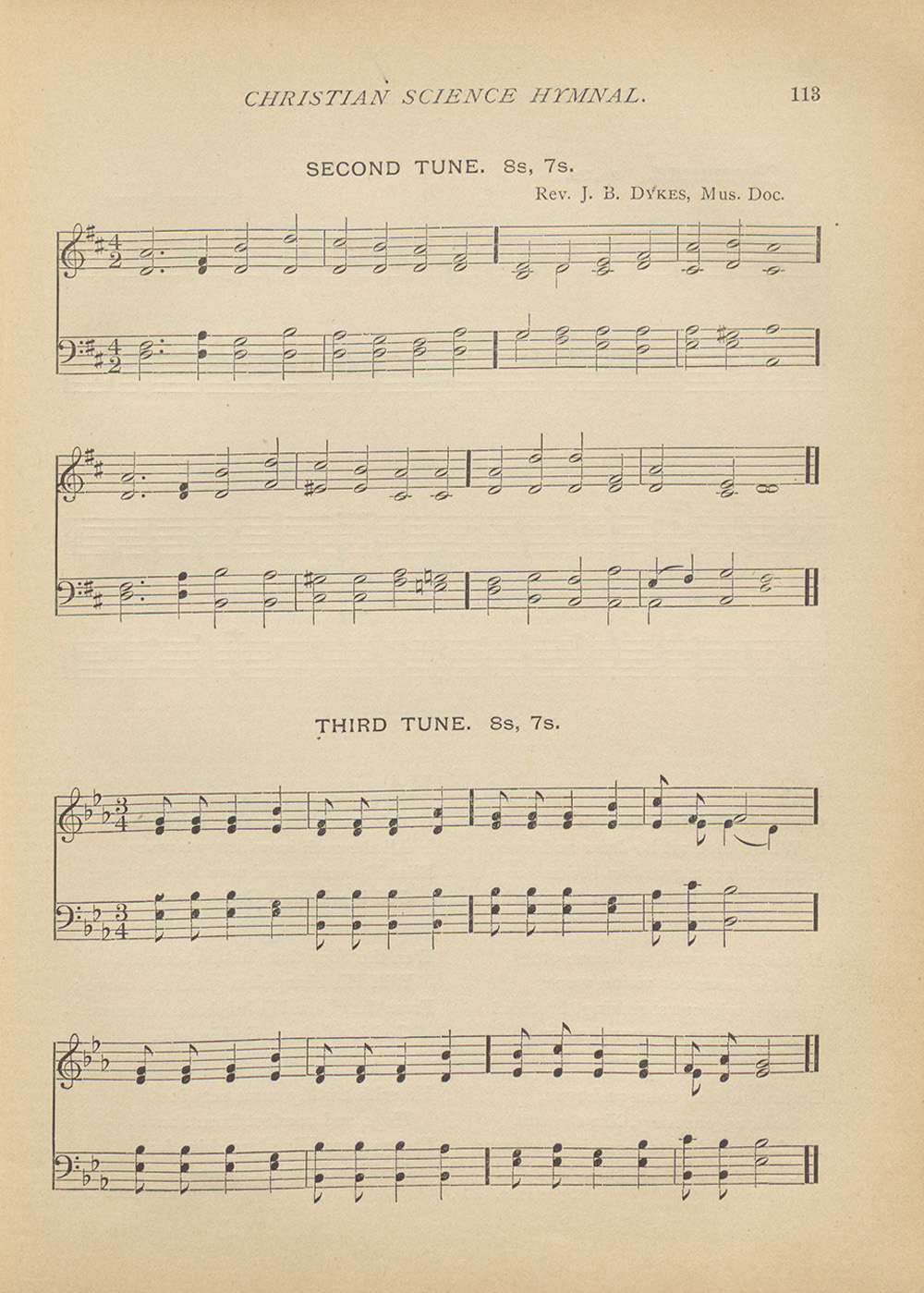

An example of how the 1892 Hymnal was set up is evident in Hymns 111 and 112, with words by J. Rowe and James Montgomery, respectively. The two texts are positioned on the left-hand page below the first tune, SICILY. The second tune, by the Rev. John B. Dykes (eventually given the tune name ST. OSWALD) and the third tune, an original by Brackett (not credited), are positioned on the right-hand page.16 Thus a congregation could sing either text to any of three tunes, since both had the same 8.7.8.7 meter. “Call the Lord thy sure salvation” moved forward through subsequent editions of the Hymnal and became number 33 in the 1932 edition.

Hymns 111 and 112, from the 1892 edition of the Hymnal, are shown below for comparison.

“From the table now retiring” (Hymn 111).

First tune

Second tune

Third tune

Dr. Peter J. Hodgson (1929–2007), a leading expert on the Hymnal, made this observation in a 1996 article:

This plan gave the hymnal a diversity of musical styles: familiar settings, examples of the highest quality from the repertory of Christian hymnody, and Brackett’s more contemporary style – music of a lighter, parlor music genre. Perhaps it was hoped that Brackett’s melodies would enliven social sacred-music making, and encourage spirited congregational singing.17

Hodgson also made these observations about four brief sets of Responses and four settings of the Gloria Patri found in the 1892 edition:

The inclusion of Responses and Gloria Patri in this first edition of the Christian Science Hymnal is of interest in that it reflects a mode of worship that, not surprisingly, linked the beginnings of Christian Science “public and social services”…(with other) Christian denominations of the period… Choirs, choral singing, and solo singing, as well as congregational singing…were part of the early Christian Science worship service. Both Responses and Gloria Patri, as well as the hymn designated for Sunday School use and special occasions, were discontinued after the 1892 edition of the hymnal. This dissolution of liturgical ties marked a final departure from the customary design and content of most denominational hymnals, with their greater emphasis on seasonal and festival occasions, leaving the Christian Science Church free to focus its denominational hymnal on its primary mission – to provide an adequate repertoire of congregational song suitable for Christian Science church services and the individual use of its members and friends, the theme of which is spiritual refreshment and healing.18

Photo of Peter J. Hodgson from the Sheaf yearbook, 1994. Neil Theisen. Courtesy of the Principia Archive.

A word about gospel hymns is appropriate here. In his 1926 book History of the Christian Science Movement, William Lyman Johnson discussed what he felt were the negative effects of this music, which had flooded the American religious scene in the Second Great Awakening (see Chapter 2). He felt that these hymns “expressed a desire for an easily learned and readily singable tune, irrespective of its value as a musical composition.”19 He expressed regret that the poorest of these hymns were often the greatest favorites, and asserted that this type of music did nothing to advance hymn-singing in American churches. In the end, only 10 gospel hymns were included in the 1892 Hymnal. Two examples are the widely popular “Bringing in the sheaves” and one of Eddy’s favorites, “Nearer, my God, to Thee.”

Contributions from key religious figures

Three poems by Eddy are of particular importance in this first edition of the Hymnal. All were set to melodies by Brackett.20 While she was the founder of the new religion, the number of her hymn texts was fairly modest when compared with the prolific outpouring of hymnic poetry by such religious figures as Congregational minister Isaac Watts (1674–1748) and Methodist leader Charles Wesley (1707–1788)—although her contributions were uniquely suited to Christian Science hymnody and to enhancing what Christian Scientists would have seen as the healing tone of their church services. A reader of the Journal, “M.A.F.,” commented in the February 1895 issue:

I have just received the Christian Science Hymnal, the first I have ever owned. It is grand. The hymns have lifted me a step higher in thought, in fact they are little sermons all the way through. The old tunes we have always known, now sung in the “new tongue” are more inspiring than ever. To-day in singing “St. Nicholas” I thought what beautiful words, but did not know until I finished, that the composer was the author of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, making the Hymnal more precious to me than ever.21

The closing decade of the nineteenth century proved an extremely active period in the development of the Christian Science movement, including the 1892 reorganization of the church and the creation of a Deed of Trust that established the Christian Science Board of Directors. The first services were held in the newly built Mother Church in Boston on December 30, 1894. They opened with Hymn 178, Eddy’s “Communion Hymn,” and closed with Hymn 111, “From the table now retiring.” The church building was dedicated the following Sunday.22 The 1890s also saw the publication of poems by Eddy that were later set to music: “The Mother’s Evening Prayer“ (1893), “Love” (1896), and “Christmas Hymn” (1898).23 As the number of Christian Science branch churches increased, the Christian Science Hymnal was one of the stabilizing and unifying elements in the blossoming religion.

“I love to tell the story”

Articles and testimonies

This section chronicles experiences of Christian Scientists who cited hymns from the Christian Science Hymnal, in articles and testimonies published in the Christian Science magazines.

“Am I My Brother’s Keeper?”

Daisy Bedford

Christian Science Sentinel, October 7, 1911

“Why Not Greater Faith?”

Ida T. Davis

Christian Science Sentinel, December 14, 1911

“This Testimony is Written in Deep Gratitude…”

Minna Gergenheimer

Christian Science Sentinel, December 16, 1913

“Words that Heal”

Annie M. Knott

Christian Science Sentinel, December 17, 1914

“For the hymn containing these words, in the Christian Science Hymnal…”

Ethel Murden

Christian Science Sentinel, June 13, 1931

Recorded hymns in this chapter are from the Christian Science Hymnal, 1892 edition, and performed by Christa Seid-Graham and Denny Veidelis (voice) and Bryan Ashley (keyboard). Video narrated and performed by Christa Seid-Graham.

© ℗ 2024 The Mary Baker Eddy Library. All rights reserved.

Chapter notes:

- Editor [Septimus J. Hanna], “The Christian Science Hymnal,” The Christian Science Journal, December 1892, 423.

- Christian Science Hymnal (Boston: Christian Science Publishing Society, 1892), Preface.

- Hymnal (1892), 159, 191.

- Anglo-Irish poets Nahum Tate (1652–1715) and Nicholas Brady (1659–1726) collaborated to produce the metrical New Version of the Psalms of David (1696).

- Hymnal (1892), 39. These words also appear as Hymn 99 in the 1932 Christian Science Hymnal, with some slight changes.

- Mary Baker Eddy, “Address. Subject: The 91st Psalm,” 28 February 1898, A10125, 1–2.

- Mary Baker Eddy, “Address. Subject: The 91st Psalm,” 28 February 1898, A10125, 1–2.

- Later she was known as Mary Alice Dayton.

- Alice Dayton, “A Word of Thanksgiving for the Christian Science Hymnal,” Journal, December 1892, 406.

- ”Potter and Clay,” Journal, September 1890, 242. Dayton’s text, with its original wording, first appeared as hymn 15 in the 1890 words-only hymn publication. It was Hymn 92 in the 1892 Hymnal.

- Hymnal (1892), Preface.

- Social Hymn and Tune Book for the Vestry and the home (Boston: American Unitarian Association, 1880).

- Isaac Watts (1674–1748) was a nonconformist minister and the parent of English hymnody. Anna L. Waring (1823–1910) was a Welsh poet and Anglican hymn writer. Alexander Ewing (1830–1895) was a Scottish musician, composer, and translator.

- Hymnal (1892), 157, 169, 161, 165, 153, 39. Arthur Sullivan (1842–1900) was an English composer best known for his 14 operatic collaborations with W. S. Gilbert; John B. Dykes (1823–1876) was an English clergyman and hymn writer; William Hoyte (1844–1917) was an organist and professor of organ in England; William H. Monk (1823–1889) was an English church musician, publisher, and composer of popular hymns; Lowell Mason (1792–1872) was an American banker and music director who composed hundreds of hymns; John E. Gould (1821–1875) managed music stores in New York and Philadelphia, and compiled eight religious songbooks.

- Brackett composed the tunes in the 1932 edition for Hymns 154 (“In Thee, O Spirit true and tender”); 197 (“Now sweeping down the years untold”); 254 (“O’er waiting harpstrings of the mind”); 298 (“Saw ye my Saviour?”); and 304 (“Shepherd, show me how to go”).

- J. Rowe (1865–1933) was an emigrant to the US from England who wrote many gospel hymns; James Montgomery (1771–1854) was a Scottish hymn writer, poet, and editor.

- Peter J. Hodgson, “The Christian Science Hymnal: An Historical Note,” (Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts: Longyear Museum Press, 1996), 4.

- Hodgson, “The Christian Science Hymnal: An Historical Note,” 5. The Gloria Patri (“Glory be to the Father”) is a brief hymn which, along with sung responses, are used in some forms of Christian liturgical worship.

- William Lyman Johnson, History of the Christian Science Movement Vol. 1 (Brookline, MA: Zion Research Foundation, 1926), 380.

- These are “Christ My Refuge,” “Communion Hymn,” and “Feed My Sheep”.

- M.A.F., “Notes from the Field,” Journal, February 1895, 485.

- “First services in new church,” Journal, February 1895, 464.

- Eddy, “The Mother’s Evening Prayer,” Journal, August 1893, 193; Eddy, “Love,” Journal, June 1896, 103; Eddy, “Christmas Hymn,” Journal, December 1898, 587.