The Christian Science Hymnal: History, Heritage, Healing

The Christian Science Hymnal: History, Heritage, Healing

The Christian Science Hymnal: History, Heritage, Healing

Listen to this article

Chapter 8

The evolution of some significant hymns

Many people who sing hymns have favorite selections—tunes they find special because of meaningful words that have brought inspiration, comfort, and healing. This chapter offers background on five hymns with special significance for people who have played and sung them. Several help illustrate the heritage of hymnody that Christian Scientists share with other Christian denominations.

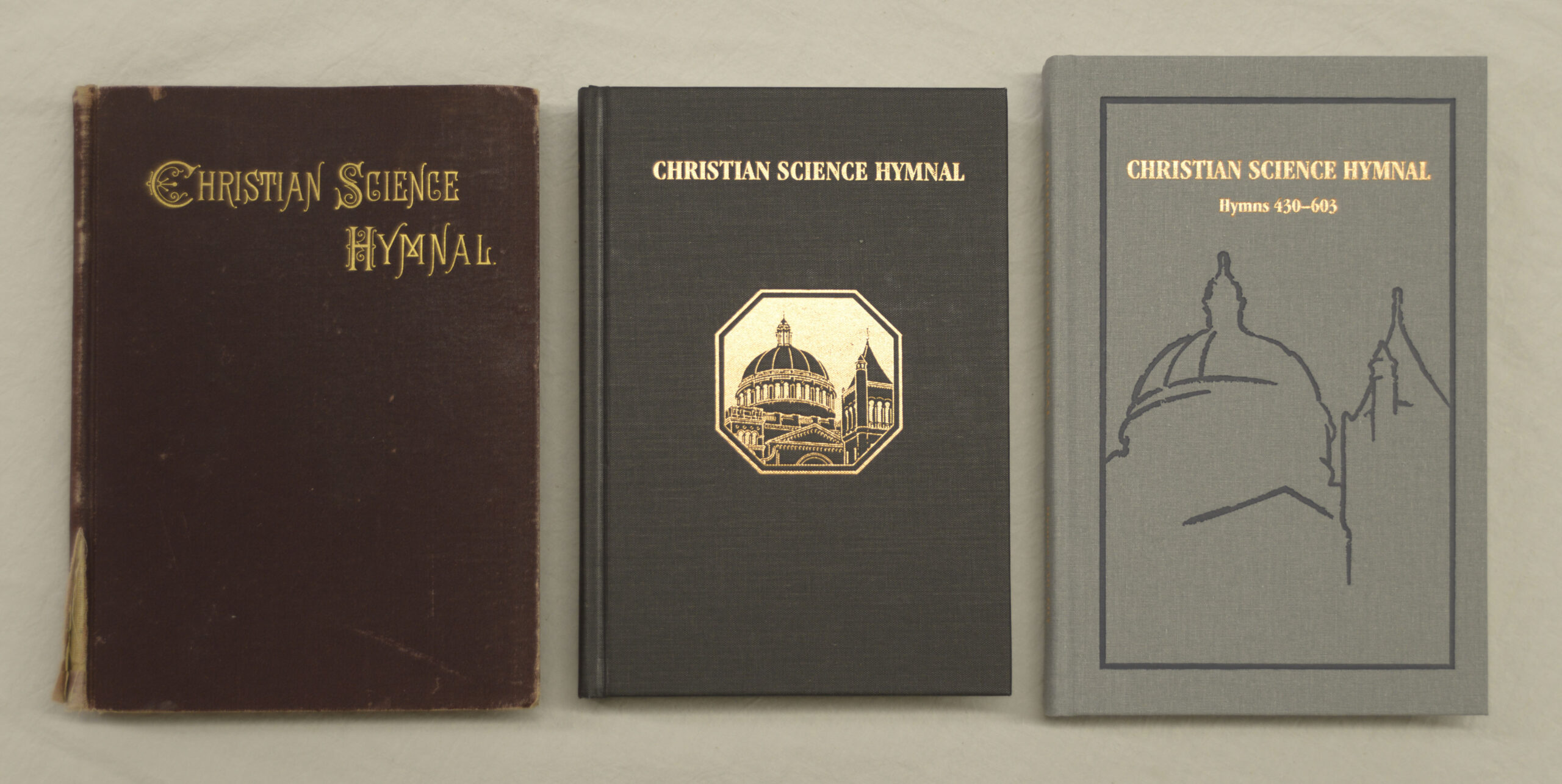

Click image to enlarge

From left: The 1892, 1932, and 2017 editions of the Christian Science Hymnal.

A note on the history of hymn tunes

Vocal and instrumental music have both accompanied worship since ancient times. But congregational singing as we know it today did not begin until the Reformation of the early sixteenth century. Martin Luther, John Calvin, and other reformers were convinced that every worshiper should be able to read and understand the Bible and be an active participant in church services. Singing scriptural verses was a natural way to accomplish these goals. And to help, significant Bible passages were “versified”—altered slightly—to make them fit with generally recognized tunes, known mostly by a “key word” taken from the original text.

As new tunes were introduced, people learned them through repeated listening. Soon congregants were able to sing many Bible verses set to a variety of tunes, each calling to mind a particular melody by its individual name. For example, the leader of one church service might announce, “We will sing Psalm 91 to BERA,’” And then at another service, “Let’s sing DAVID’S HARP with Psalm 91.”1

Although the practical need for tune names disappeared when hymns began to appear in print, the tradition of assigning names to hymns continued. Some tune names are descriptive, such as Felix Mendelssohn’s BETHLEHEM, which is used as the setting for Hymn 311 in the 1932 Christian Science Hymnal (“Sing, ye joyous children, sing”). Other names may point to personal references, such as William Lyman Johnson’s use of PLEASANT STREET and CONCORD for tunes he set to Mary Baker Eddy’s poems “Christ, My Refuge” ( “O’er waiting harpstrings of the mind”) and “Feed My Sheep” (“Shepherd, show me how to go”). The 1932 edition includes the name for each hymn tune in capital letters at the top left of the page. Newer hymnals, such as the 2017 edition, show each tune name at the lower right.

Hymns 1, 62, 63, 445–447: “Be Thou, O God, exalted high” and “From all that dwell below the skies”

Many hymnologists think that the tune related to these hymns, OLD HUNDREDTH or OLD HUNDRED, is the most famous of all Christian hymn tunes. Louis Bourgeois (c. 1510–1560) was largely responsible for creating the Genevan Psalter of 1551—a monumental musical publication finally completed in 1562. The 1551 edition is where the tune first appeared, set to words from Psalm 134.2

OLD HUNDREDTH is the tune name peculiar to England, while OLD HUNDRED is more commonly used in America and Scotland. The hundredth Psalm was originally known as the “Hundredth,” but after the appearance of a new 1696 version by two Anglo-Irish poets, Nahum Tate (1652–1715) and Nicholas Brady (1659–1726),3 the word “Old” was added to the name.4

This sacred song is a doxology—usually a liturgical expression of praise to God.5 Short doxological hymns are used in various forms of Christian worship, often added to the end of canticles, psalms, and hymns.

This tune was prepared for the French version of Psalm 134. In the Genevan Psalter, the original words set to this tune are translated “You faithful servants of the Lord, sing out his praise with one accord.” This version was included in the Anglo-Genevan Psalter of 1551. The first English words set to this melody were by the Scottish Bible translator William Kethe. His version of Psalm 100, “All People That on Earth Do Dwell,” became so popular that the tune became known as THE HUNDREDTH.

In 1696 Tate and Brady published a new version of the Anglican Psalter, in which the word “Old” was used in the tune’s title, to show that it was the one used in the previous and beloved 1562 psalter, edited by John Hopkins (?–1570) and Thomas Sternhold (1500–1549).

The music is in long meter: 8.8.8.8. This means that there are four phrases, with each phrase containing eight syllables. For this reason, every text adapted to the tune must also be in long meter. Here are some examples of texts set to this tune:

“Be Thou O God exalted high”6

- “All people that on earth do dwell” (William Kethe: ?–1594)

- “Praise God from whom all blessings flow” (Thomas Ken: 1637–1711)

- “From all that dwell below the skies” (Isaac Watts: 1674–1748)

In the first edition of the Christian Science Hymnal (1892), this tune appeared as Hymn 1, with two sets of words. The more famous were written in 1718 by Isaac Watts—“the father of English hymnody.”7 Below is his versification (metrical version) of Psalm 117, on which the hymn text is based:

From all that dwell below the skies

Let the Creator’s praise arise;

Let the Redeemer’s name be sung

Through every land, by every tongue.Eternal are Thy mercies, Lord;

Eternal truth attends Thy word;

Thy praise shall sound from shore to shore,

Till suns shall rise and set no more.

The second set of words in the 1892 edition began “I praise thee, Lord, for blessings sent.” No author was identified.8

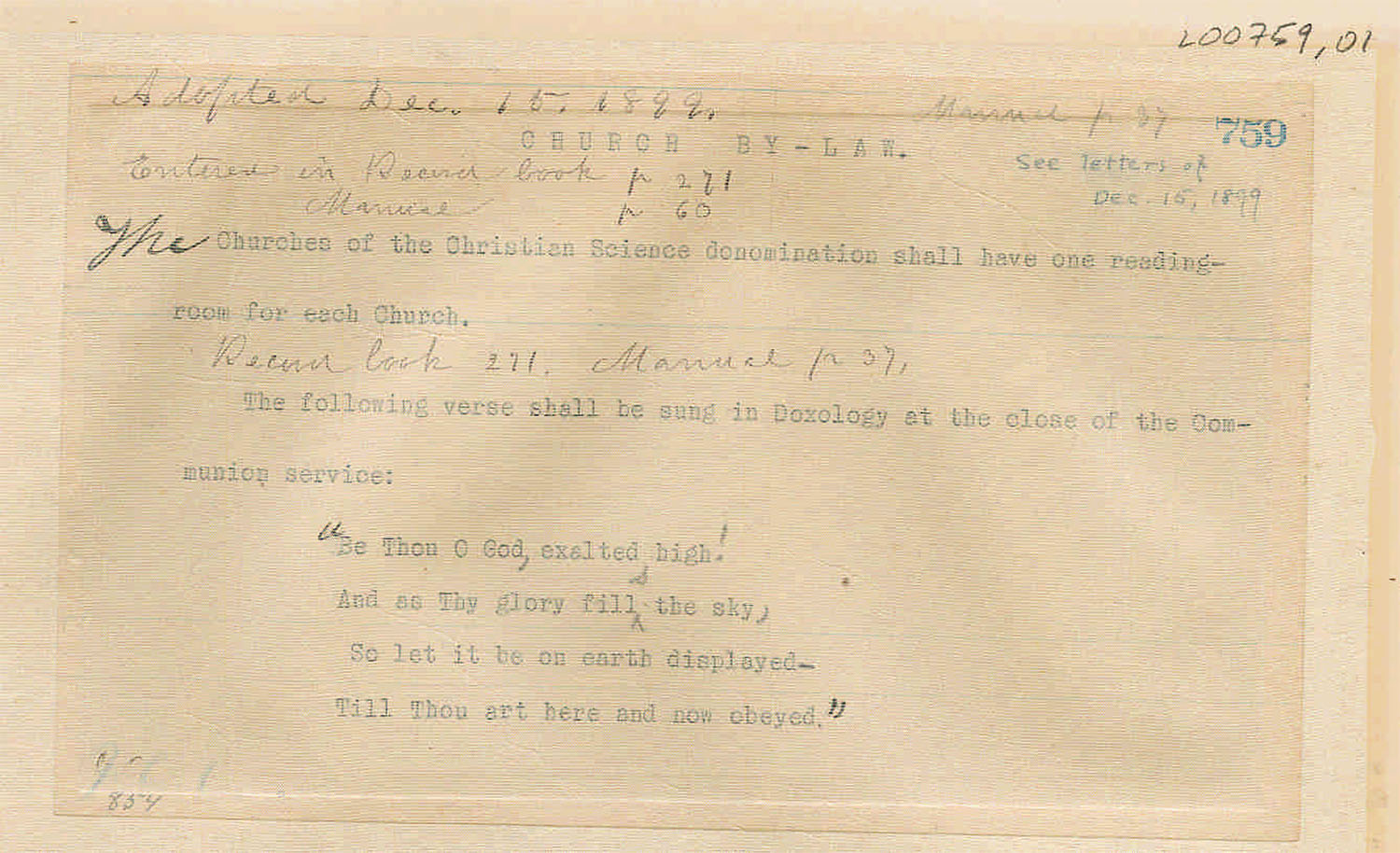

The 1898 revision of the Hymnal was printed every year, in order to satisfy demand. On December 15, 1899, a By-Law was adopted for the Manual of The Mother Church, which said in part, “The following verse shall be sung in Doxology at the close of the Communion service.”9 In 1900 The Christian Science Journal and the Christian Science Sentinel published the text of Psalm 57:5 from the 1696 Tate and Brady Psalter:

Be Thou, O God, exalted high;

And as Thy glory fills the sky,

So let it be on earth displayed,

Till Thou art here and now obeyed.10

This became the Communion Doxology—the “praise-speaking”—of the Christian Science church. It was first published in the 1901 printing of the 1898 Hymnal, with slight alterations to Mary Baker Eddy’s words:

A note on the history of hymn tunes

Vocal and instrumental music have both accompanied worship since ancient times. But congregational singing as we know it today did not begin until the Reformation of the early sixteenth century. Martin Luther, John Calvin, and other reformers were convinced that every worshiper should be able to read and understand the Bible and be an active participant in church services. Singing scriptural verses was a natural way to accomplish these goals. And to help, significant Bible passages were “versified”—altered slightly—to make them fit with generally recognized tunes, known mostly by a key word taken from the original text.

As new tunes were introduced, people learned them through repeated listening. Soon congregants were able to sing many Bible verses set to a variety of tunes, each calling to mind a particular melody by its individual name. For example, the leader of one church service might announce, “We will sing Psalm 91 to BERA.’” And then at another service, “Let’s sing DAVID’S HARP with Psalm 91.”11

Although the practical need for tune names disappeared when hymns began to appear in print, the tradition of assigning names to hymns continued. Some tune names are descriptive, such as Felix Mendelssohn’s BETHLEHEM, which is used as the setting for Hymn 310 in the 1932 Hymnal (“Sing, ye joyous children, sing”). Other names may point to personal references, such as William Lyman Johnson’s use of PLEASANT STREET and CONCORD for tunes he set to Mary Baker Eddy’s poems “Christ, My Refuge” ( “O’er waiting harpstrings of the mind”) and “Feed My Sheep” (“Shepherd, show me how to go”). The 1932 edition includes the name for each hymn tune in capital letters at the top left of the page. Newer hymnals, such as the 2017 edition, show each tune name at the lower right.

Desirée Goyette composed this tune (“EXALTED,” Hymn 447) for the Doxology text by Tate and Brady. It appears in the 2017 Hymnal alongside two other new Doxology tunes. 12

Be Thou, O God, exalted high;

And, as Thy Glory fills the Sky,

So let it be on Earth display’d;

Till Thou art here, as there, obey’d.

Be Thou, O God, exalted high;

And as Thy glory fills the sky,

So let it be on earth displayed,

Till Thou art here and now obeyed.

This appeared as the first hymn, although it was at the time unnumbered. The same tune followed it with Isaac Watts’s words. These two versions lived back-to-back until they were decoupled in the 1932 edition, at which point Watts’s text took its place in alphabetical order, appearing as Hymns 62 and 63. Historian Peter J. Hodgson wrote that Eddy’s “choice of a psalm verse for the lead text in the Hymnal suggests the importance she attached to the Bible as a source of inspiration for songs sung in her church.”13

In late January 1900, William B. Johnson, Clerk of The Mother Church, forwarded a question to Eddy from a Christian Science branch church musician, asking her to clarify the By-Law about the Doxology—did it apply only to The Mother Church, or were branch churches supposed to adopt it as well?14 The Sentinel soon offered this clarification: “This is the order of service of the Mother Church, and the branch churches shall adopt this form of service.”15

Table: Use of OLD HUNDRED in hymnals for Christian Scientists

To hear the tune OLD HUNDREDTH, see the related musical example in Chapter 5 of this series.

Click image to enlarge

Draft of two By-Laws for the Manual of The Mother Church, December 15, 1899. L00759.

Hymns 51, 52, 467, 468: “Eternal Mind the Potter is”

In 1890, two years prior to the first official hymnal, Christian Science practitioner Mary Alice Dayton (?–1940) offered her poem “Potter and Clay” to the Journal. “The following grew out of a suggestion that [Christian] Science should by this time bring forth words for its own Hymnal,” she wrote. “It is offered without any attempt at self-justification or maternal pride.”16 Published anonymously, the poem was wedded to the tune SPOHR in the 1892 Hymnal, and the hymn has since been beloved among Christian Scientists.

Cherie Brennan composed the tune “CONSCIOUSNESS” (Hymn 468) as a setting of Mary Alice Dayton’s text. It appears in the 2017 Hymnal alongside another setting.17

In her “History and Reminiscences,” Dayton recalled the origins of the work:

At the close of the College class in 1889 the editor of the C.S. journal made an appeal to the members to write for it. He said our periodical needed the loving support of the thought educated rightly in Science. My pledge was given, but the argument that experience was not sufficient to warrant my contributing, had prevented any action.

One day the desire to express gratitude brought forth the recognition that God would supply the theme and give it form. I turned to the Bible and read a verse about potter and clay; then looked at a sentence in Science and Health on the same line. Often I had read what poets had said about shaping character by moulding, but these were tinged with a sadness and suffering. What would Science say about this? The first lines came at once, quickly followed by the others. My only effort was to state my thought carefully so that it might be in line with the teachings of Truth, and not mislead any one who saw them. When the call for words for a hymnal for Science was sent out I recommended “How firm a foundation,” but enclosed my verses not expecting they would be considered. They were printed in the next issue of the Journal, and later placed in the hymnal. This episode proved to me that God blesses every sincere desire and makes it fruitful.18

Biblical references in the hymn text include words from Jeremiah 18:4 (“potter,” “clay,” “hand”); Romans 8:17 (“Christ,” “heir”); and Matthew 6:10 and Luke 11:2 (“will,” “kingdom”).

Hymn 148: “In heavenly Love abiding”

Anna L. Waring (1823–1910) was born into a Welsh Quaker family. She joined the Church of England in her teens and was baptized in 1842. A lifelong student of Hebrew, she read daily from the book of Psalms in the original text. In her adult years she devoted herself to prison ministry and causes such as the Discharged Prisoners’ Aid Society.19

In 1850 Waring published a poem that began “In heavenly love abiding” in her Hymns and Meditations by A.L.W., a little volume of 19 hymns. She titled it “Safety in God.” It is also found in the Social Hymn and Tune Book (Hymn 291). With its first line changed to “In heavenly Love abiding,” the poem was set to EWING, the work of Scottish musician, composer, and translator Alexander Ewing (1830–1895). This tune and harmonization remain basically the same to the present day.

Two hymnals compiled by early Chicago Christian Scientists Joseph Adams and Jessie Day (see Chapter Two) featured “In heavenly Love abiding.” The hymn has been included in every Christian Science Hymnal edition. Along the way, a few words were altered and the capitalization changed. For example, while the 1892, 1898, and 1910 editions of the Hymnal contained the line “My shepherd is beside me,” the 1932 edition restored Waring’s capitalization of the word “Shepherd,” elevating it to express the divine concept of God as the Shepherd of humanity.

Listen to three arrangements of EWING (“In heavenly Love abiding,” Hymn 148)

Kenny Baker, From the Christian Science Hymnal: Hymns Sung By Kenny Baker, Volume 1 (c. 1950)

McHenry Boatwright, Faculties Indestructible (1967)

Doreen Burkhart, His Song Shall Be with Me: Hymns for Morning and Evening (1974)

Hymns 192, 193: (“Nearer, my God, to Thee”)

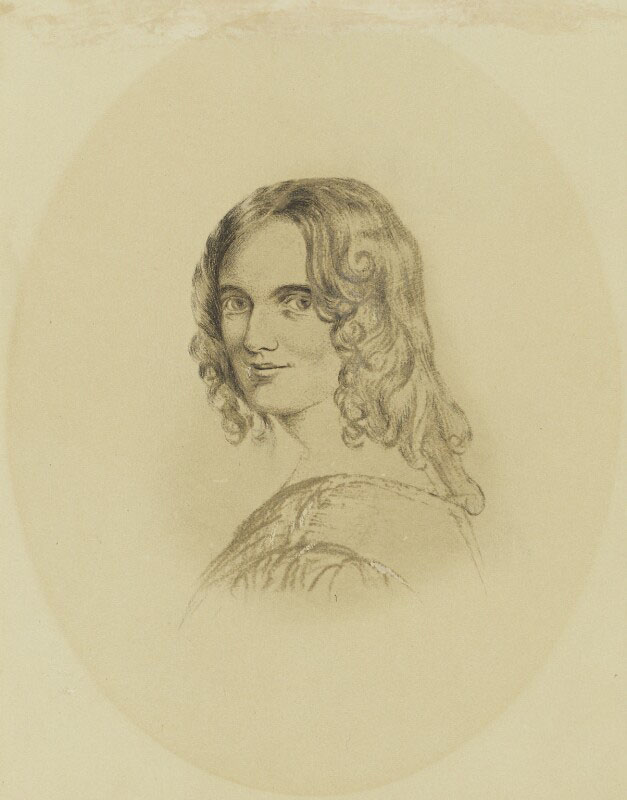

Born in Harlow, England, Sarah Flower Adams (1805–1848) had aspirations of an acting career and once played Lady Macbeth in London. She was, however, plagued by ill health and instead focused on her literary gifts.

One day in 1841 her pastor, Rev. William Johnson Fox (1786–1864) of London’s South Place Unitarian Church, came to call. He wanted to include some of Adams’s texts in a hymnbook he was compiling. But he said he was confounded by the inability to find an appropriate hymn to support his message for the upcoming Sunday sermon on the story of Jacob at Bethel (see Genesis 28).

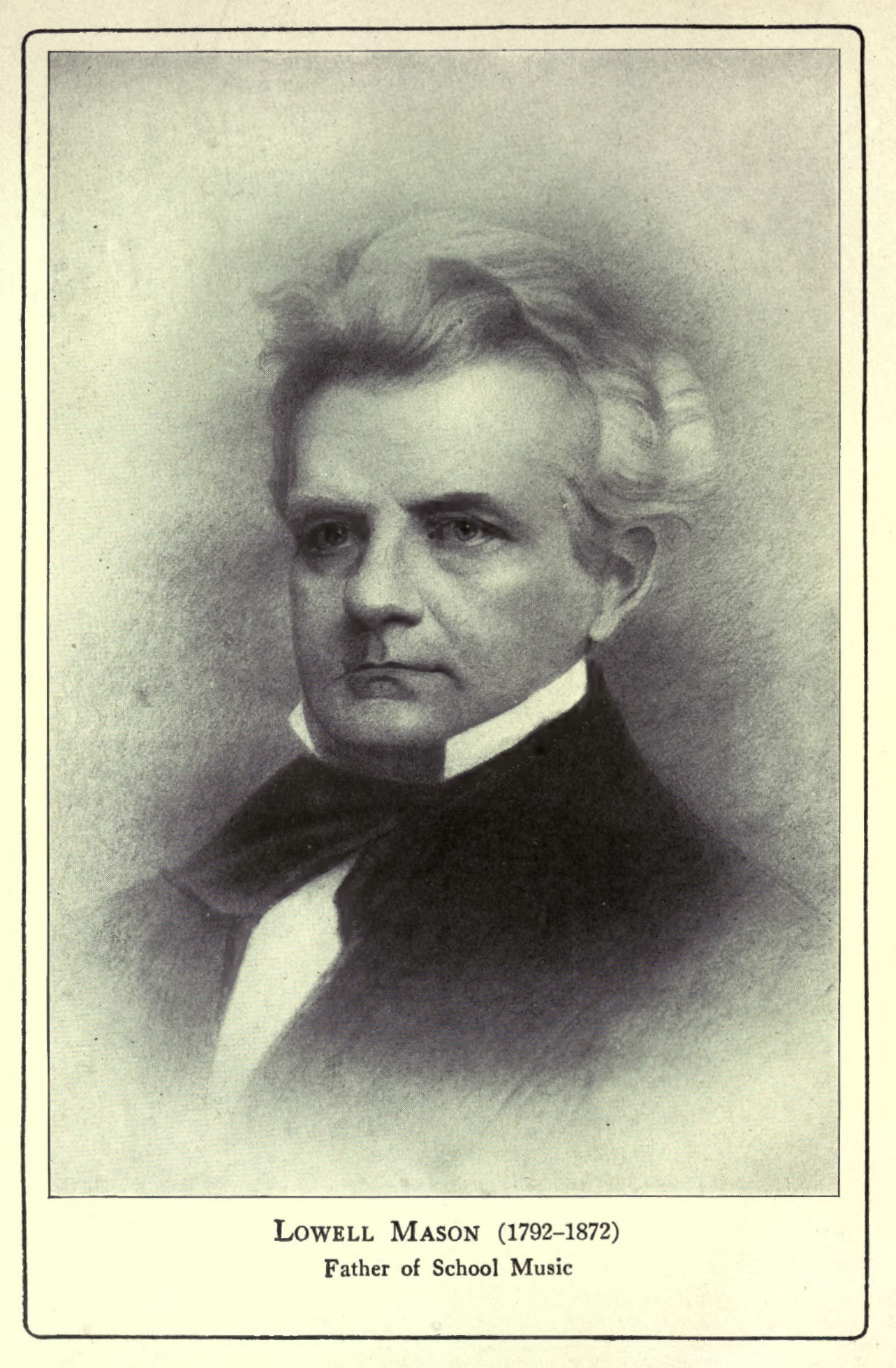

For the rest of the week, Adams pored over the passage, visualizing Jacob sleeping with a stone for his pillow and dreaming of a ladder that reached to heaven. The following Sunday, Fox’s congregation sang her words ““Nearer, My God, to Thee,” first published that same year in his Hymns and Anthems. In 1856 American musician Lowell Mason (1792–1872) set her text to a tune he titled BETHANY.20

“Nearer, My God, to Thee” is a famous example of a gospel song (see Chapter 1). According to William J. Reynolds and Milburn Price, it “had its roots in American folk melody….” Their book A Survey of Christian Hymnody observes, “Of…importance were the camp-meeting collections, the singing-school texts books, and the songs designed for use in the Sunday School movement.” And they conclude that “all these forces met, merged, and contributed to the development of the gospel song.”21

Chicago Christian Scientists Ursula Gestefeld and Joseph Adams adapted Sarah Adams’s version for their respective hymnals, published in 1889 (see Chapter 2) and offered interpretations based on their new religion (both eventually left Christian Science). It is not known to what tune Joseph Adams’s words were set; his verses contain seven lines, while all other versions contain eight. Here is a comparison of their texts with the original by Sarah Adams:

Hymns 192, 193: (“Nearer, my God, to Thee”)

Born in Harlow, England, Sarah Flower Adams (1805–1848) had aspirations of an acting career and once played Lady Macbeth in London. She was, however, plagued by ill health and instead focused on her literary gifts.

One day in 1841 her pastor, Rev. William Johnson Fox (1786–1864) of London’s South Place Unitarian Church, came to call. He wanted to include some of Adams’s texts in a hymnbook he was compiling. But he said he was confounded by the inability to find an appropriate hymn to support his message for the upcoming Sunday sermon on the story of Jacob at Bethel (see Genesis 28).

For the rest of the week, Adams pored over the passage, visualizing Jacob sleeping with a stone for his pillow and dreaming of a ladder that reached to heaven. The following Sunday, Fox’s congregation sang her words ““Nearer, My God, to Thee,” first published that same year in his Hymns and Anthems. In 1856 American musician Lowell Mason (1792–1872) set her text to a tune he titled BETHANY.22

“Nearer, My God, to Thee” is a famous example of a gospel song (see Chapter 1). According to William J. Reynolds and Milburn Price, it “had its roots in American folk melody….” Their book A Survey of Christian Hymnody observes, “Of…importance were the camp-meeting collections, the singing-school texts books, and the songs designed for use in the Sunday School movement.” And they conclude that “all these forces met, merged, and contributed to the development of the gospel song.”23

Chicago Christian Scientists Ursula Gestefeld and Joseph Adams adapted Sarah Adams’s version for their respective hymnals, published in 1889 (see Chapter 2) and offered interpretations based on their new religion (both eventually left Christian Science). It is not known to what tune Joseph Adams’s words were set; his verses contain seven lines, while all other versions contain eight. Here is a comparison of their texts with the original by Sarah Adams:

(view these hymns side-by-side)

Click image to enlarge

Sarah Flower Adams, after Margaret Gillies. Photograph of drawing, touched with chalk, 1850-1875. NPG 1514. © National Portrait Gallery, London. View licensing and copyright terms.

Click image to enlarge

Bookplate of Lowell Mason in What We Hear in Music: A Laboratory Course of Study in Music History and Appreciation by Anne Shaw Faulkner, c. 1913.

Sarah Adams (1841)

Nearer, my God, to thee

Nearer to thee;

E’en though it be a cross

That raiseth me,

Still all my song shall be

Nearer, my God, to thee,

Nearer, my God, to thee,

Nearer to thee.

Though like the wanderer,

The sun gone down,

Darkness be over me,

My rest a stone,

Yet in my dreams I’d be

Nearer, my God, to thee,

Nearer, my God, to thee,

Nearer to thee.

There let the way appear,

Steps unto heav’n;

All that thou sendest me,

In mercy giv’n;

Angels to beckon me

Nearer, my God, to thee,

Nearer, my God, to thee,

Nearer to thee.

Then with my waking thoughts

Bright with thy praise,

Out of my stony griefs

Bethel I’ll raise;

So by my woes to be

Nearer, my God, to thee,

Nearer, my God, to thee,

Nearer to thee.

Or if, on joyful wing

Cleaving the sky,

Sun, moon, and stars forgot,

Upward(s) I fly,

Still all my song shall be

Nearer, my God, to thee,

Nearer, my God, to thee,

Nearer to thee.

Ursula Gestefeld (1889)

Nearer, my God, to Thee,

Nearer to Thee,

Since I the Truth perceive,

I cannot be:

In Thee I live and move,

Leaning alone on Love,

Nearer, my God, to Thee,

I cannot be.

Never a wanderer,

Never alone,

Encircling me the Light,

I am Thine own;

E’en in this dream, of Thee

Conscious I now may be,

Nearer, my God, to Thee,

I cannot be.

Now doth the way appear

Steps up to heaven,

All that I am and have

From Thee is given;

Thy thoughts are waking me,

Clearly, my God, to see,

Nearer, my God, to Thee,

I cannot be.

Thus every thought shall be,

bright with Thy praise;

Out of my consciousness,

Bethel I’ll raise;

There are no woes for me,

This blessed Truth I see,

Nearer, my God, to Thee,

I cannot be.

Swift on the wings of Truth,

Rising on high;

Earth senses all forgot,

Upward I fly;

Now all my song shall be,

Ever, my God, with Thee,

Nearer, my God, to Thee,

I cannot be.

Joseph Adams (1889)

Nearer I cannot be

My God to Thee

In Thee I live and move,

Sustaining me.

Thy love, my song shall be,

More of my God I see

Always with me.

Never a wanderer;

The sun not down,

No darkness covers me

In sleep alone.

For in my dreams I’d be

Conscious, my God, of thee,

Never from me.

Then with my waking thoughts,

Bursting with praise;

Out of my sense of Thee

Bethel I’ll raise.

So shall my moments be

Joyous, my God, with thee,

Sweet harmony.

Brighter the way appears,

Lighted with heaven,

In which Our Father lives,

With His children.

Spirit thoughts teaching me

Glories, my God, of thee,

Baptizing me.

Soaring on joyful wing,

Thinking of Him,

Sickness and woes forgot,

Evil and Sin.

Always, my song shall be,

More of my God, to see,

My life to be.

Click image to enlarge

Sarah Flower Adams, after Margaret Gillies. Photograph of drawing, touched with chalk, 1850-1875. NPG 1514. © National Portrait Gallery, London. View licensing and copyright terms.

Click image to enlarge

Bookplate of Lowell Mason in What We Hear in Music: A Laboratory Course of Study in Music History and Appreciation by Anne Shaw Faulkner, c. 1913.

Referring to Eddy’s words in Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures24 in his essay “The Evolution of the Christian Science Hymnal,” college professor Paul Williams observed, “The Christian demand to come out and be separate has somehow been lost from the Gestefeld version, and the entire original meaning of the hymn has been inverted.” Discussing the old gospel tune “Rock of Ages,” Williams also pointed to “the tendency observable in the Gestefeld hymnal [to concentrate] on the personality of Jesus rather than on the presence of the Christ in human experience.”25

Listen to a contemporary arrangement of BETHANY (“Nearer, my God, to Thee,” Hymn 192): Larry Groce, On Joyful Wing (2008)

Hymn 264: “Onward, Christian soldiers”

This work is connected with Whit Monday, a holiday in the Christian liturgical calendar celebrated on the day after Pentecost. In 1865 English clergyman and writer Sabine Baring-Gould (1834–1924) recalled the hymn’s origins:

Whit-Monday is a great day for school festivals in Yorkshire. One Whit-Monday, thirty years ago, it was arranged that our school should join forces with that of a neighboring village. I wanted the children to sing when marching from one village to another, but couldn’t think of anything quite suitable; so I sat up at night, resolved that I would write something myself. “Onward, Christian Soldiers” was the result. It was written in great haste, and I am afraid some of the rhymes are faulty. Certainly nothing has surprised me more than its popularity. I don’t remember how it got printed first, but I know that very soon it found its way into several collections. I have written a few other hymns since then, but only two or three have become at all well-known.26

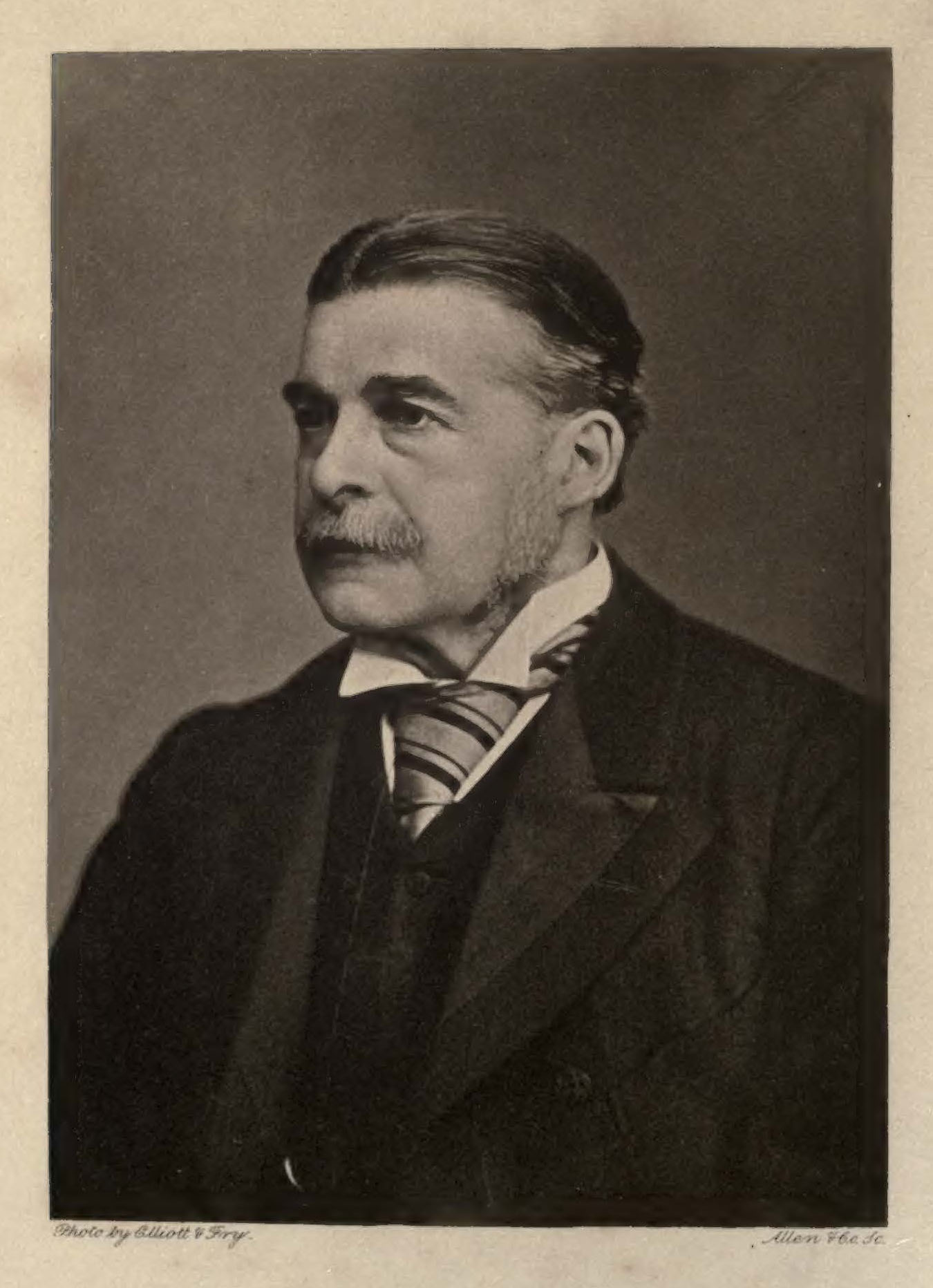

Arthur S. Sullivan (1842–1900) wrote the music for “Onward, Christian soldiers” in 1871 and named the tune ST. GERTRUDE, after the wife of a friend at whose country home he had composed it.27

ST. GERTRUDE (“Onward, Christian soldiers,” Hymn 264). Audio excerpted from The Mary Baker Eddy Library’s webcast “Faith, Freedom, and the Great War—Religious Meaning in World War I” (2018).

Click image to enlarge

Sabine Baring-Gould, 1892. Chronicle / Alamy Stock Photo.

Click image to enlarge

Sir Arthur Sullivan, c. late 1800s. Elliot & Fry.

“I love to tell the story”

This section chronicles experiences of Christian Scientists who cited hymns from the Christian Science Hymnal, in articles and testimonies published in the Christian Science magazines.

Articles and testimonies

“Our New Hymnal”

Mabel Cone Bushnell

Christian Science Sentinel, July 8, 1933, 888

“How grateful I am for the hymns in the Christian Science Hymnal”

Ruth Barlow Simons

Christian Science Sentinel, June 27, 1977, 1186–1187

“I have had many healings…”

Carolyn Cummings with contribution from Donna Cummings

Christian Science Sentinel, September 3, 1979, 1563–1564

“One day after coming home…”

Chrystal Rein with contribution from Wendy Rein

Christian Science Sentinel, March 14, 1983, 464–466

“Hymns: uplifting thought to God”

Freda Sperling Benson

The Christian Science Journal, March 1984, 138–139

“The very first Christian Science healing I had…”

Dais Taylor

The Christian Science Journal, April 1996, 60

“Healing of a heart condition”

Dorothy Dipuo Maubane

Christian Science Sentinel, August 10, 1998, 22

Recordings of Hymns 447 and 468 are from Christian Science Hymnal: Hymns 430–603 (audio). © ℗ 2017 The Christian Science Publishing Society. Recordings of Hymn 148 are from the following albums from The Christian Science Publishing Society: From the Christian Science Hymnal: Hymns Sung By Kenny Baker, Volume 1 (c. 1950); Faculties Indestructible (1967); His Song Shall Be with Me: Hymns for Morning and Evening (1974). Recording of Hymn 192 is from On Joyful Wing. ℗ 2008 The Christian Science Publishing Society. Audio excerpt of Hymn 264 is from the webcast “Faith, Freedom, and the Great War—Religious Meaning in World War I.” ℗ 2018 The Mary Baker Eddy Library.

- BERA and DAVID’S HARP appear in the 1932 Christian Science Hymnal as Hymn 99 and Hymn 100, respectively.

- “Loys Bourgeois: French Composer,” Britannica online:https://www.britannica.com/biography/Loys-Bourgeois, accessed 2 April 2024; Concordance to Christian Science Hymnal and Hymnal Notes (Boston: The Christian Science Publishing Society, 1975), 175–176.

- Hymnal Notes, 175–176.

- Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, fifth edition, vol. VI (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1954), 184.

- Hymnal Notes defines doxology as “praise-speaking” (175).

- Christian Science Hymnal, 1932 edition, Hymn 1. This is a versification of Psalm 57:5 (King James Version): “Be thou exalted, O God, above the heavens; let thy glory be above all the earth.”

- Hymnal Notes, 204.

- See Hymnal Notes, 236–237 for possible authorship.

- Mary Baker Eddy, 15 December 1899, L00759. This By-Law, “Doxology,” appeared in the Manual from the 14th edition (1900) through the 28th edition (1903).

- Mary Baker G. Eddy, “BY-LAWS,” The Christian Science Journal, January 1900, 702; Mary Baker G. Eddy, “By-laws,” Christian Science Sentinel, 4 January 1900, 288.

- BERA and DAVID’S HARP appear in the 1932 Christian Science Hymnal as Hymn 99 and Hymn 100, respectively.

- To read more about OLD HUNDREDTH and listen to an audio sample, see Chapter 5.

- Peter J. Hodgson, “The Christian Science Hymnal: An Historical Note,” (Chestnut Hill, MA: Longyear Museum Press, 1996), 26.

- William B. Johnson to Mary Baker Eddy, 26 January 1900, A10332A.

- “Order of Communion Service,” Sentinel, 15 February 1900, 384.

- “Potter and Clay,” Journal, September 1890, 242.

- To read more about Dayton and listen to a different setting of “Eternal Mind the Potter is,” see Chapter 3.

- Mary Alice Dayton, “History and Reminiscences,” 11.

- hymntime.org: http://www.hymntime.com/tch/bio/w/a/r/i/waring_al.htm, accessed 22 April 2024.

- “‘Nearer, My God, to Thee:’ The History and Lyrics,” The Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square, https://www.thetabernaclechoir.org/articles/nearer-my-god-to-thee-history-and-lyrics.html?lang=eng, accessed 2 April 2024; Concordance to the Christian Science Hymnal, 259.

- William J. Reynolds and Milburn Price, A Survey of Christian Hymnody, third edition (Carol Stream, IL: Hope Publishing Co., 1987), 99.

- “‘Nearer, My God, to Thee:’ The History and Lyrics,” The Tabernacle Choir at Temple Square, https://www.thetabernaclechoir.org/articles/nearer-my-god-to-thee-history-and-lyrics.html?lang=eng, accessed 2 April 2024; Concordance to the Christian Science Hymnal, 259.

- William J. Reynolds and Milburn Price, A Survey of Christian Hymnody, third edition (Carol Stream, IL: Hope Publishing Co., 1987), 99.

- See Eddy, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 451.

- Paul Williams, “The Evolution of the Christian Science Hymnal,” (Special Collections, Principia College Library, 1979), 7.

- “‘Onward, Christian Soldiers’ (Baring-Gould),” Hymntime.com: http://www.hymntime.com/tch/htm/o/n/w/a/onwardcs.htm, accessed 2 April 2024.

- Concordance to the Christian Science Hymnal, 286.