From the Papers: Leo Tolstoy and Mary Baker Eddy

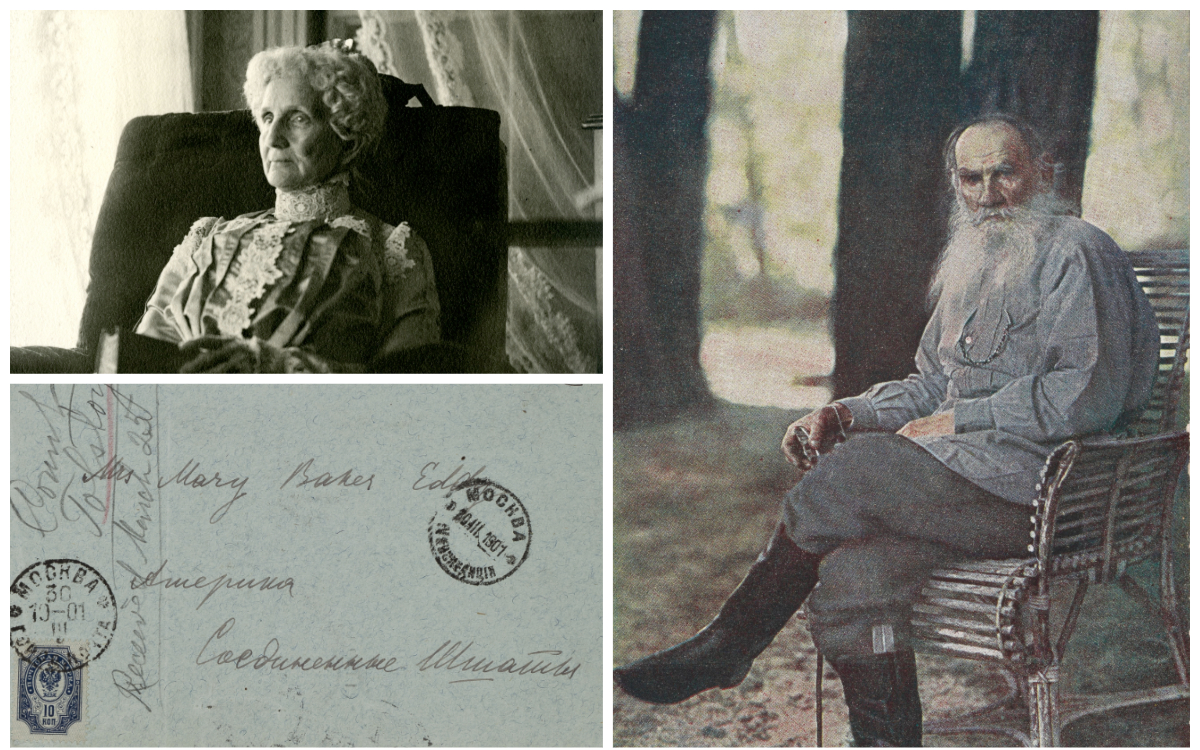

Portrait of Mary Baker Eddy by Calvin Frye, c.1892–1908, P00060, © TFCCS. Leo N. Tolstoi in Iasnaia Poliana, by S. M. Prokoudine-Gorsky. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ds-02147. Sergei Tolstoy to Mary Baker Eddy, March 1901, 718AP1.87.018.

Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910)1 was a Russian writer, regarded today as one of the greatest and most influential authors of all time. His most notable works include the epic novels War and Peace (1869), Anna Karenina (1878), and Resurrection (1899). Tolstoy and Mary Baker Eddy were prominent figures during the latter half of the nineteenth century. Through their moral teachings and literary works, both made a significant impact on Christian thought. But were they aware of each other? The Mary Baker Eddy Library houses correspondence, books, and scrapbooks that make important connections between Tolstoy and Eddy—and showcase a mutual respect for each other’s work.

Although residing on opposite sides of the world, both Tolstoy and Eddy went through deep spiritual transformations later in life that endured the rest of their lives. Discussing her own awakenings, Eddy stated in her autobiographical work Retrospection and Introspection, “…in the latter part of 1866 I gained the scientific certainty that all causation was Mind, and every effect a mental phenomenon.”2

Mary Baker Eddy in her study, c. 1892–1908. Calvin A. Frye. P00036.

Eddy was 44 years old when she discovered Christian Science, as a result of healing through Bible reading (including Matt. 9:2), after a fall on the ice that had rendered her unconscious. Tolstoy famously embraced Christianity when he was around 50. He declared in his 1884 work What I Believe that he found spiritual healing while reflecting on the Gospel of Matthew:

Of all the gospels, the Sermon on the Mount was the portion that impressed me most, and I studied it more often than any other part. Nowhere else does Christ speak with such solemnity; nowhere else does He give us so many clear and intelligible moral precepts, which commend themselves to everyone. If there are any clear and definite precepts of Christianity, they must have been expressed in this sermon; and, therefore, in those three chapters of St. Matthew’s gospel I sought the solution of my doubts.3

Tolstoy in his study in Yasnaya Polyana, May 1908. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Prokudin-Gorskii Collection, LC-DIG-prok-01970.

Both Tolstoy and Eddy believed in Jesus’ teachings and in love as a guiding principle, and they spent the rest of their lives on work that reflected this conviction. They died within two weeks of each other in late 1910. The December 17, 1910, issue of the Christian Science Sentinel compiled excerpts from other periodicals reporting on Eddy’s death, including the New York American, which drew a comparison:

So wide-spread is the fame of Mary Baker Eddy that there is no country in the world that will not take note of her death. Her extraordinary influence upon her generation will everywhere suggest comparisons or contrasts between her work and that of the seer who died in Russia a few days ago. Count Tolstoi spoke to the intellect and Mrs. Eddy to the heart. Nobody has any right to doubt the sincerity of either; though every one will think and feel as he pleases or as he can—concerning their wisdom and inspiration.4

A look through the Library’s collections reveals Eddy’s distinct interest in Tolstoy’s life and works. Her personal library contained copies of The Kreutzer Sonata (1889) and Work While Ye Have the Light (1890)—both of which she marked up in pencil.5 The Mary Baker Eddy Collection contains scrapbooks that include various articles about Tolstoy, including a copy of an interview with him in the February 24, 1901 issue of the New York World, on which several of his statements have been marked.6

Snapshot of a scrapbook page containing the beginning of an interview with Tolstoy. There are parentheses drawn around this quotation: “Sickness and suffering destroy what is mortal in man solely to prepare him for something better.” SB012, 152.

The Library also houses an exchange of related correspondence. In the summer of 1900, when she was living in Concord, New Hampshire, Eddy heard that Tolstoy was ill. She wrote to her student Anna B. White Baker, asking that she send him two copies of her book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures:

Please help me to send my Science and Health to the dear old martyr of this century, Count Tolstoi. I want him to have God’s staff to lean upon Whenever the enemy presses hard I “smile” with the venerable Count. They tell me he is ill I must get my book to him7

Baker sent a message on March 19, 1901, along with Science and Health, to the Tolstoy family estate, Yasnaya Polyana:

The Rev. Mary Baker Eddy, commissioned me to send to you her book, “Science & Health, with Key to the Scripture” … which has established here in this Country and abroad a practical religion that sees the need of the Science of the Truth which Jesus of Nazareth came to teach & preach, & which is doing a grand and noble work today.8

Tolstoy may have been one of the first people in Russia to have read Science and Health. Within the month his eldest son, Sergei Tolstoy, sent a letter of acknowledgement and thanks to Eddy on his father’s behalf.9 Two months later, on May 2, 1901, Eddy also sent Tolstoy a copy of her book Miscellaneous Writings, 1883-1896. In a letter accompanying the parcel, she noted where in that book Tolstoy could find a testimonial that explained how someone became interested in Science and Health.10 Perhaps by choosing to point out this particular item she was speaking to what she believed Tolstoy might take special interest in; he had noted in October 1897 that one can “understand and feel God when one has understood clearly the unreality of everything material.”11 In Science and Health Eddy had written this as a beginning to her “scientific statement of being”:

“There is no life, truth, intelligence, nor substance in matter. All is infinite Mind and its infinite manifestation, for God is All-in-all.”12

The anonymous testimonial in Miscellaneous Writings, which Eddy endorsed in her letter to Tolstoy, speaks along those same lines:

…any who will lay aside their preconceived notions, and deal honestly with themselves and the light they have, will come to a knowledge of the truth as illustrated in the teachings and life of Jesus Christ; that is, that Mind, or Soul, or whatever you may be pleased to call it, is the real Ego, or self, and that mortal mind with its body is the unreal and vanishing, and eventually goes back to its native nothingness….To one who can accept the truth that all causation is in Mind, and who therefore begins to look away from matter and into Mind, or Spirit, for all that is real and eternal, and for all that produces anything that is lasting, the doubts and petty annoyances of life become dissolved in the light of a better understanding, which has been refined in the crucible of charity and love; and they fade away into the nothingness from whence they came, never having had any existence in fact, being only the inventions of erring human belief. Read the teachings of the Christ from a Christian Science standpoint, and they no longer appear vague and mystical, but become luminous and powerful,—and, let me say, intelligible.13

It appears that for Tolstoy and Eddy there was a mutual interest in each other’s work. The library of the Tolstoy family estate numbers some 22,000 books, including several of Eddy’s works, some of which contain notations in Tolstoy’s hand. And William D. McCrackan, who later served as President of The First Church of Christ, Scientist, wrote to the New York World in 1901, stating that he had “…received a communication signed by [Tolstoy’s] daughter… that her father never felt anything but respect for Christian Science.”14

Many of the sources mentioned here (correspondence, books, and annotated scrapbook pages) can be viewed in-person at The Mary Baker Eddy Library. Some can also be found on the Mary Baker Eddy Papers website by clicking on the links included in this article. Examining these items, one is able to gain valuable insight into how these two prominent figures viewed each other, their Christian beliefs, and their life’s work.

Please note: Quoted references in our “From the Papers” article series reflect the original documents. For this reason they may include spelling mistakes and edits made by the authors. In instances where a mark or edit is not easily represented in quoted text, an omission or insertion may be made silently.

- He is also known as Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy.

- Mary Baker Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 24.

- Leo Tolstoy, What I Believe (London: Elliot Stock, 1885), 7–8.

- “Excerpts from Editorial Comments.” Christian Science Sentinel, 17 December 1910.

- See B00305 and B00306 at the Mary Baker Eddy Library for these annotations.

- SB012, 152–153.

- Mary Baker Eddy to Anna B. White Baker, 1900, F00204, https://mbepapers.org/?load=F00204

- Anna B. White Baker to Leo Tolstoy, 19 March 1901, V03595, https://mbepapers.org/?load=V03595

- Sergei Tolstoy to Mary Baker Eddy, March 1901, 718AP1.87.018, https://mbepapers.org/?load=718AP1.87.018

- Mary Baker Eddy to Leo Tolstoy, 2 May 1901, V03596, https://mbepapers.org/?load=V03596

- Leo Tolstoy, The Journal of Leo Tolstoi (First Volume–1895-1899) / translated from the Russian by Rose Strunsky (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1917), 152.

- Mary Baker Eddy, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 468:9–11.

- Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896, (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 469–470.

- “Count Tolstoi and Christian Science” Sentinel, 8 August 1901.