From the Papers: Celia Osgood Peterson: Christian Scientist and public educator

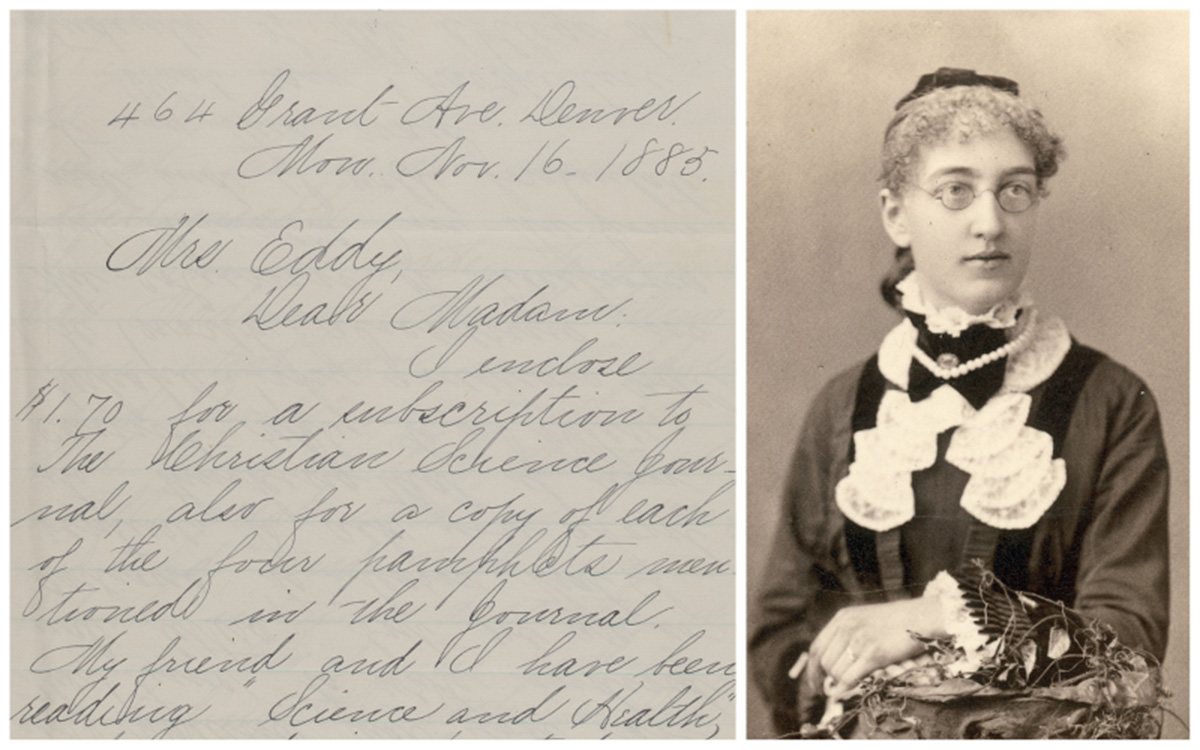

Celia F. Osgood Peterson to Mary Baker Eddy, November 16, 1885, 699B.82.026. Detail of Celia F. Osgood, 1880, courtesy of Denver Public Library Special Collections, Z-8041.

Listen to this article

The letters sent to Mary Baker Eddy introduce us to some of the many people taking an interest in Christian Science as it became more prominent. While these often provide us with the individuals’ names and perhaps a sense of what brought them to Christian Science, further research can uncover more details about who they were and how they intersected with other important events and movements of their time.

One such person was Celia F. Osgood Peterson, a Colorado teacher who first wrote to Eddy in the mid-1880s and went on to play important roles in the field of education. Born in Maine in 1862, Peterson was brought up in Massachusetts, and graduated as valedictorian from Malden High School in 1879. Her family then moved to Denver, Colorado, where she completed another year of high school and began her career as a teacher in the city’s public schools.

Peterson had “grown up in an atmosphere of progressive thought,” where she recalled “the expressions in her home, on the part of her parents and their friends, of a belief in the equality of man and woman and equal rights and privileges for both in every department of life.”1 In this way, she might have been naturally well-prepared to take an interest in Christian Science, a new religion founded by a fellow New England woman.

Her first letter to Eddy, written on November 16, 1885, reveals that her introduction to Christian Science came in the form of healing. She wrote, “One of your students is healing the sick in Denver with marvelous success, and has come into my home with blessing that mortal power can never repay.”2 Her second letter, written in May 1886, provides more detail:

Personally, C. S. has done everything for me, I have always been considered the reverse of strong, and my work has been hitherto done on will power against heavy odds of fatigue and exhaustion. Now I know there is a mightier than will power, and I am an incarnation of health and strength, and no longer know what it is to be tired. The change in me is not one that carries such force of conviction to the out-sider, as the cure of a disease or deformity, but to me it is just as great and wonderful as if I had been healed of belief in consumption.3

At that point Peterson was a few years into her career as a public school teacher, and her letters to Eddy reflect the perspective of someone accustomed to taking a thorough and systematic approach to learning. Her first letter requested copies of all the available literature on Christian Science and also asked, “What can prospective students of the [Massachusetts Metaphysical College] do as preliminary study, and do you regard the study of literature and languages at the same time objectionable?”4 Eddy responded to this question in the question and answer section of the February 1886 Christian Science Journal (the response was later included in her book Miscellaneous Writings 1883–1896).

In her second letter, she thanked Eddy for her response. “I have already begun to treat my immediate friends, and with excellent success,” she wrote. “I know I am not wrong in doing so, for I follow implicitly the instructions in ‘Science and Health,’”5 and so far as my limited knowledge does extend, I know it cannot be mistaken.”6 Although Peterson didn’t take Christian Science class instruction with Eddy, as she had expressed a desire to do in her letters, she did join the Christian Science church (The First Church of Christ, Scientist) in January 1898, an indication that her interest in Christian Science was ongoing.

Peterson continued on to pursue a significant career in Colorado during a period of major progressive reforms across the United States, particularly in education. School had previously been viewed more as supplemental to the learning that took place in the family and community, but toward the end of the nineteenth century it was becoming the primary mode of education.7 States were passing compulsory school attendance laws, as did Colorado in 1889.8 They were also developing standards for curriculum and organizing schools in new ways. A conversation on national educational policy was beginning to take place, with the field becoming more professional and educators starting to form national ties through new associations, publications and organized training. Voluntary organizations such as the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, as well as philanthropic and reform organizations, were also taking an interest. Public schools and increased investment in education were viewed as a means of addressing some of the social problems resulting from industrialization, protecting democracy and providing for the individual and collective well-being of citizens in a rapidly changing era. 9

Peterson was directly participating in many of these conversations and reforms. Her written contributions can be found in educational journals and reports of the time, and the same journals also mentioned her involvement with teacher trainings and papers delivered at conferences. She was also a leader in organizing the Denver Teachers’ Club and served as its first president in 1897.10

Alongside these endeavors, she was a charter member of the Woman’s Club of Denver, founded in 1894, which like many other women’s clubs of the time existed both to provide enriching educational experiences for its members and engage in philanthropic projects. Again her focus was on education, as she served on the club’s education committee.11

In June 1898 Peterson resigned from teaching in Denver’s public schools and married Joseph E. Peterson. But her career did not end. In September 1898 she took the role of Teacher of Methods and United States History in Denver Normal and Preparatory School. The following year she was appointed to serve as deputy to the elected superintendent of public instruction for Colorado, Helen Loring Grenfell. An article on this topic referred to Peterson as “an equally brilliant woman, who is devoted to the cause of education and a writer of note along educational and progressive thought lines.” It went on to say this:

Mrs. Peterson was appointed entirely upon merit, and without any political pull whatever, she being a Democrat, while the state superintendent is a Republican. If for no other reason than that women will consider fitness for office rather than party, they are more desirable for public offices of trust and responsibility…. Inasmuch as both the superintendent and her deputy have devoted their lives to public school work, they are especially well fitted to take charge of the educational interests of the state….12

The qualities Peterson expressed as a teacher and leader align with those described in Eddy’s works as important to the practicing Christian Scientist. One can imagine, then, that Peterson found Christian Science to be supportive in her work. But we can discover more specifically what Christian Science meant to her through a short article that she published in the Christian Science Sentinel on April 19, 1900. “The difference between the ignorance of Christian Science and the understanding of it,” she wrote, “is like the difference between groping timidly along a dark road, with the purpose and the end of the journey utterly unknown, and that of walking fearlessly along an illuminated pathway, conscious of a glorious purpose and an end which, if still unknown, can bring nothing but Love.”13

Stories like Peterson’s enrich what we know about early Christian Scientists and the roles they were playing in their communities. They also invite us to reflect on how the questions they asked, the things they did, and the qualities they expressed might apply to our own lives as well. Peterson’s story is just one of many that the Mary Baker Eddy Papers team is uncovering in our work.

- Elnore M. Babcock, “Women Educators,” Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), 2 May 1899.

- Celia F. Osgood Peterson to Mary Baker Eddy, 16 November, 1885, IC699B.82.026, https://mbepapers.org/?load=699B.82.026

- Celia F. Osgood Peterson to Mary Baker Eddy, 7 May, 1886, IC593B.61.020, https://mbepapers.org/?load=593B.61.020

- Celia F. Osgood Peterson to Mary Baker Eddy, 16 November, 1885, IC699B.82.026, https://mbepapers.org/?load=699B.82.026

- Eddy’s textbook on Christian Science, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, was first published in 1875.

- Celia F. Osgood Peterson to Mary Baker Eddy, 7 May 1886, IC593B.61.020, https://mbepapers.org/?load=593B.61.020

- Tracy L. Steffes. School, Society, and State: A New Education to Govern Modern America, 1890-1940.(Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), 10.

- Woman’s Club of Denver Collection. History Colorado. MSS.1662. Book #111, Education Department Minutes 1896-1899.

- Tracy L. Steffes. School, Society, and State: A New Education to Govern Modern America, 1890-1940.(Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2012), 4, 6.

- “The Denver Teachers’ Club,” Colorado School Journal, March 1899, 168.

- Woman’s Club of Denver Collection. History Colorado. MSS.1662. Books #141-144, Woman’s Club of Denver yearbooks, 1896-1900.

- Elnore M. Babcock, “Women Educators,” Harrisburg Telegraph (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), 2 May, 1899.

- Celia F. Osgood Peterson, “The Difference,” Christian Science Sentinel, 19 April 1910, 541.