From the Papers: Intellectual affinity vs. understanding—a minister’s struggle

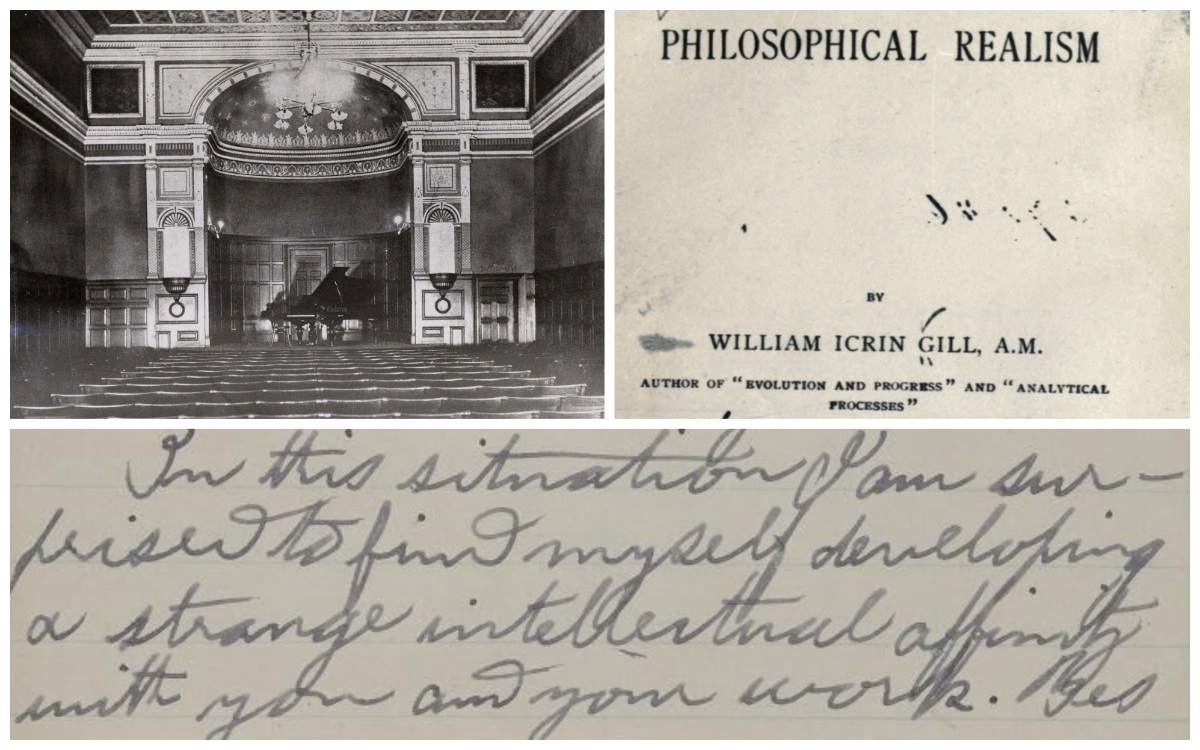

Chickering Hall auditorium, P04938; Philosophical Realism by William I. Gill; William I. Gill to Mary Baker Eddy, April 16, 1886, 215.36.005.

As Mary Baker Eddy went about establishing Christian Science, she looked for promising helpers to fill important positions. This involved roles such as teacher, editor, and publisher. It also included a need for pastors of Christian Science churches.

One candidate was the clergyman William I. Gill (1831–1902). Eddy tapped him as both assistant pastor of her Church of Christ (Scientist) and editor of the recently formed Christian Science Journal. Gill brought to these positions valuable experience and an interest in her new religion—as well as notable philosophical and theological differences.

Gill was one of several ministers who had studied with Eddy during the 1880s. A native of England, he had been a Methodist minister who was pastoring a church in Lawrence, Massachusetts at the time he was learning of Christian Science. Gill took a scholarly and intellectual approach to Christianity. The author of four books—Evolution and Progress, Analytical Processes, Christian Conception and Experience, and Philosophical Realism—he’d also published articles in several journals, including The Christian Register and Zion’s Herald.

Gill had been studying Eddy’s teachings for about a year before he enrolled in one of her classes, which began on March 29, 1886. After it concluded, he wrote her on April 16:

…I am surprised to find myself developing a strange intellectual affinity with you and your work. … Three months ago, yes three weeks before I sat as your pupil in the class in your house, I should have laughed at the prediction of such a thing. Yet I had with much respect for more than a year been studying your doctrine; and it had gradually been gaining on me. But I did not appreciate it anything like as I do now.

I now see that you are and will be one of the greatest benefactors of our times. You are contributing to the elevation of the average intellectual level, and to put a new glory on Christianity by restoring its pristine power, with a clearer understanding of its essential character. Your work will neither be abortive nor short-lived. …

I should be happy in any way to serve the cause you lead and represent, so far as my abilities and opportunities permit.1

Eddy responded in a letter no longer extant, but which was apparently part of a discussion that he would continue as pastor of his church in Lawrence but at the same time become the assistant pastor of the Church of Christ (Scientist) in Boston, with Eddy continuing as its pastor. This appointment took place in July.

The two exchanged many letters following the class. Gill acknowledged his growing conviction of the truth of Christian Science, his faith in Eddy’s leadership, and his desire to serve her and her cause. He even offered critiques of writings by other authors, such as Warren Felt Evans, whose books explicated ideas of the “mind cure,” a movement often confused with Christian Science that eventually developed into the New Thought movement:

A friend loaned me one of the books of Mr. Evans. I have just got through its perusal. I have had enough of him. In some respects he is good but very prosy, and very pantheistic. He does not inspire me with any religious feeling, notwithstanding his talk of Paul and Christ and God. His God is only a subtle matter or magnetic force universally diffused, as it seems to me.2

In September Gill was appointed Editor of The Christian Science Journal, but only served in that capacity through November. During that time the magazine contained metaphysical articles by Gill, as well as excerpts from his sermons and summaries of them. That period also exposed convictions, actions, and disagreements on his part that would ultimately lead to his resignation of both positions, as well as his expulsion from the Christian Scientist Association. At length he cut all ties to the Christian Science movement. Gill’s sense of intellectual superiority attended conflicts with other Christian Scientists, and he advertised his newly published book, Philosophical Realism, in the Journal as though it was a work on Christian Science.3

In addition, Gill had a major disagreement with Eddy’s theology and questions came to the surface that had not been apparent in his writing and speaking on the subject. Eddy taught that God is infinite Spirit, the one divine Mind that is wholly good and cannot know or be conscious of evil, any more than light could be conscious of or conceive of darkness. On the other hand, while Gill could accept God as wholly good, he also insisted that God must of necessity be able to cognize an evil opposite to His own completely good nature.

The potential of Gill’s views to hamper an accurate understanding and practice of Christian Science came to the fore in a conversation he and Eddy had on Thanksgiving Day 1886, when she invited him and his family to dinner, along with some other Christian Scientists.

That evening Gill began a long letter to Eddy and added to it the next day, outlining the mental turmoil he was experiencing as a result of their conversation, sharing his own thoughts:

It is clear that God cannot know (by experience, impression, acquisition) evil; but He must be able to understand it as the logically contrasted opposite of himself, as a falsity, a claim to be what it is not. I have all along thought that this must be what you mean. If it is not, I am in deep distress. I cannot connect it with my highest thinking and moral action.4

Eddy replied in a long letter of her own, including this:

This law of God is universal infinite and eternal by virtue of God’s Allness and that God cannot know what is outside of Divine knowing namely that there is something beside Him, Good. But His law reaches with its spirit and intelligent working every error supposable because it is the law that defines God as All and that there is none beside Him, hence that there is no error

The above is Christian Science, nothing in the premise or conclusion is contradictory or confusing to the most intellectual logical thought.5

Eddy continued in another letter dated the next day:

Mine is Divine philosophy without a human taint that cannot be misguided You do not understand this philosophy fully, so far as you do you explain it well Other students of mine go beyond you in this understanding even as the child Jesus said was greatest in this kingdom because more receptive of Truths that human understanding had not reache but the Divine Spirit had revealed

No student understands all I say or do, and never will on this plane for I shall grow faster than they even as interest accumulates faster in proportion to the principal …

I have no human understanding or motives that influence me that I am not striving to destroy that I may let in more light

May God bless you I pray, O for the sight given you of what is darkening you and that you could see my heart’s desire to promote your happiness and success now and forever6

A further cause for Eddy’s concern about Gill came in the form of reports that he was using his own book, Philosophical Realism, as the sole textbook for his classes while representing them as instruction in Christian Science,7 and that he had begun to introduce into his sermons ideas that were contrary to Eddy’s teachings. His resignation came In January 1887, followed by his expulsion on February 2.

Gill’s post-Christian Science activities included attacks on Eddy and her teaching, as well as association with exponents of the mind-cure movement. After he published an article brimming with hostility toward Eddy and Christian Science in the spiritualist and mind cure publication Religio-Philosophical Journal,8 Eddy’s student Melville C. Spaulding wrote her an undated letter, commenting on her tendency to look to ordained ministers as among those with particular qualifications to assume important positions in the Christian Science movement:

Your love of the church of your childhood has followed you into C.S. and can be distinctly traced through your wonderful book & later writings–and your partiality towards the Clergy & Church has been one of the weak props of your cause–a cause which needed no such artificial supports…l have just read Mr. Gill’s “article” in the Religio Philosophical Journal … You are fortunate in losing Mr. Gill.9

It seems likely that Eddy believed in clergymen who had apparently adopted Christian Science, feeling they could be of service to the Christian Science movement because of their love of the Bible and Christianity and desire to live the teachings of Jesus. However, some amounted to no more than “a flash in the pan.” In addition to Gill, other unsuccessful associations included those with the Congregationalist minister Joseph A. Adams, the Scottish minister H.C. Waddell, John S. Norvell, and George B. Day.

Other ministers, however, proved able to let go of philosophical and theological differences. Such individuals as Lanson P. Norcross, David A. Easton, and Irving C. Tomlinson laid aside former ecclesiastical ties and admirably served the cause of Christian Science for the rest of their lives.

- William I. Gill to Mary Baker Eddy, 16 April 1886, 215.36.005.

- Gill to Eddy, 6 July 1886, 215.36.018.

- See “Philosophical Realism” on page 78 of the June 1886 issue of The Christian Science Journal and “Philosophical Realism” by Mary B. G. Eddy on page 211 of the December 1886 issue of the Journal.

- Gill to Eddy, 25 November 1886, 215.36.025.

- Eddy to Gill, 26 November 1886, L02555.

- Eddy to Gill, 27 November 1886, V00978.

- See for example Alfred Lang to Eddy, 2 December 1886, 294.42.009.

- Founded in 1865, the Religio-Philosophical Journal was published in Chicago until 1905.

- Melville C. Spaulding to Eddy, undated, 572.59.018.