From the Papers: Letters from the western frontier

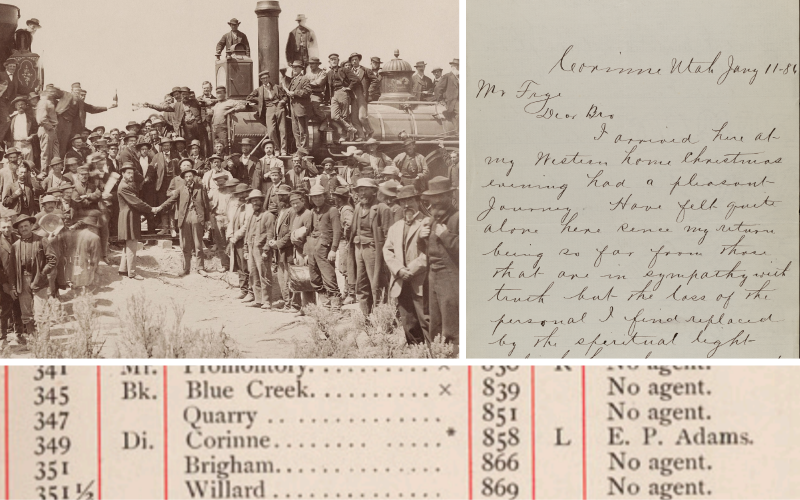

Photo: East and West shaking hands at laying last rail of Union Pacific Railroad, May 10, 1869, by Andrew J. Russell. Courtesy of Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Letter: Edward P. Adams to Calvin A. Frye, January 11, 1886, 938.91.006. Table: Central Pacific Railroad Official list of officers, stations, distances, etc., 1884, page 55. Courtesy of California State Railroad Museum Library.

The mid-1880s saw rapid growth in the number of students who received Christian Science instruction from Mary Baker Eddy—as well as the students of her students. Many people are familiar with the stalwart workers credited with growing the Christian Science movement during that time, thanks to accounts of their successful healing and teaching practices in urban centers beyond Boston, such as New York, Milwaukee, Chicago, Omaha, and Denver.

However, another important means by which Christian Science spread was the quiet, earnest sharing of individual healing experiences in small, rural communities far from the urban centers. As is becoming more evident to the Mary Baker Eddy Papers team, these writers are unfamiliar, at least in part, because they did not establish large teaching and healing practices. Many sent only a handful of letters—perhaps even just one—back to Boston. These humble lives shaped, and were shaped by, the westward movement in the United States. And they, too, can be credited for the rapid spread of Christian Science from New England to the West Coast.

One such example recently came to light in our ongoing work of transcribing and annotating Eddy’s correspondence: Edward P. Adams (1842–1920), who studied Christian Science with Eddy. Born in Gilead, Maine, he began working for the Grand Trunk Railway and Montreal Telegraph Company in Gorham, New Hampshire, around the age of 16. He remained there until December 1873, when the Central Pacific Railroad appointed him to the role of station agent at Corinne, Utah.1

Adams took Eddy’s Primary class in Boston in November 1885. A letter he wrote to her on October 27, 1885, suggests he may have been introduced to Christian Science by Sarah H. Crosse, also of New Hampshire.2 He joined the Christian Scientist Association in December 1885, before returning to his post in Corinne.

On January 11, 1886, he wrote a letter to Calvin Frye, ordering a copy of Eddy’s newly revised 16th edition of Science and Health, and noted:

I arrived here at my Western home Christmas evening had a pleasant Journey. Have felt quite alone here since my return being so far from those that are in sympathy with truth but the loss of the personal I find replaced by the spiritual light which has been my great gain …. please give my love to dear Mrs Eddy who I hold in most grateful remembrance for this new life that she has opened to me3

This letter may appear unremarkable at first. But in fact it opens a window on a fascinating time and place in United States history. And it demonstrates the unique opportunity Adams had to share his commitment to Christian Science in his thriving, if somewhat rough-and-tumble, frontier town. As a station agent, he held a prominent position with the railroad—the most central and important enterprise in what further research reveals was a somewhat unusual location.

Corinne, Utah, was established in March 1869. It is about 25 miles from the place where, on May 10, 1869, the final “golden spike” was driven into the railroad tracks at Promontory Summit, joining the Central Pacific Railroad with the Union Pacific Railroad, completing the final link in the transcontinental railroad. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) was expanding in Utah, and some of its leaders had expressed concerns about the effects the railroad might have on its members by opening up the area to the rest of the country. At times, non-Mormon businesses were boycotted.4 As a result, a group of non-Mormon merchants and retired army officers established Corinne. They anticipated being able to freely pursue business opportunities and other activities centered around, and enabled by, the completion of the new railroad. In a history of Corinne, author Catherine Armstrong writes that the town sprang up almost overnight:

More than 500 buildings and canvas tents housed over 1,000 residents. The railroad town had 28 saloons, 16 liquor stores, a few dance halls and a no-nonsense Marshall to keep everyone in check. Corinne was soon known as the ‘Gentile Capital of Utah,’ where miners, railroad workers, shippers and freighters could go for entertainment and commerce.5

In addition to quickly establishing itself as the region’s principal freighting center, Corinne had, by the early 1870s, a large hotel, opera house, newspaper, warehouses, factories, mills, and churches representing at least seven different denominations. Its founders even envisioned that it might become the eventual capital of Utah, which at that time was still a US territory.6

It was against this dynamic backdrop that Adams read his new copy of Science and Health and considered his prospects for sharing about his “new life” in Christian Science. He was one of several students to whom Eddy sent a letter in May 1886. “I see the great need for Christian Scientists to establis[h] public schools in all our principal Cities,” she stated, asking them to “[o]pen a public institute in some chief city at once.“7

While Adams did not end up opening an institute, he sent this reply to Eddy on on July 4, 1886:

your teachings have saved me much suffering I should at this time be a hopeless invaled but for the truth which you teach and which I learned while in the Class the burden of suffering of years has been rolled away and a glimpse of the perfect life appears.

I cannot understand how there can be a doubt the reward comes with every effort made for divine truth It is my chief desire to leave all other employment and go into active work for my Masters Cause the field of suffering and error is large and there is no laborers here. I think a good work might be done in Utah with earnest labor the Mormon influence which is great would be the principal opposition I hope that you may have the satisfaction of seeing the seed from your labor planted throughout the land8

Given that sentiment, it is hard to imagine that Adams did not speak to as many others as possible about his spiritual healing of invalidism and “glimpse of the perfect life,” doing his part to sow the seeds of Christian Science “throughout the land.” Although we have no record of correspondence between Adams and Eddy after 1888, we know that he remained committed to Christian Science and joined The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in 1896.

In the late 1870s, the Utah-Northern Railroad was built, connecting Ogden, Utah, to a rail line in Idaho. This cut off Corinne as a main supply point. Subsequently many of the town’s businesses relocated to Ogden. In 1904 another rail line was constructed that further marginalized the town’s access to the main routes and caused the remainder of its business, industry, and population to collapse.9 Corinne experienced the same boom-bust cycle that was the hallmark of many western towns during this period in United States history. It transformed from the once-aspiring Utah capital into the quiet farming community that it is today. Likely for this reason, Adams moved on as well. While we don’t know the details, he eventually made his way to Alameda, California, where he passed away in 1920.

From 1842 to 1920, from Maine to California, Adams’s life coincided with the greatest and most dynamic westward expansion and growth in the history of the United States. Significantly associated with one of the main catalysts, the transcontinental railroad, he was moreover a faithful student of Christian Science who touched many other lives on his ever-westward journey. His brief correspondence exemplifies the lesser known—yet collectively monumental—contributions of the far-flung individuals whose own lives were transformed by Christian Science and remained dedicated to spreading its influence wherever circumstances took them.

The Mary Baker Eddy Papers collection contains many letters from the Western frontier. Each letter highlights some unique aspect of how the growth of Christian Science in the late nineteenth century was interwoven with America’s growth—and reveals the contributions of the one who wrote it.

- “Presentation to Mr. E. P. Adams,” Journal of the Telegraph, Vol. VII, No. 3, Feb. 1, 1874, p. 55, https://books.google.com/books?id=myxOAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA55&lpg=PA55&dq=”E.+P.+Adams”+”central+pacific+railroad”&source=bl&ots=rwHq1kFEii&sig=ACfU3U0yDi_jkvpTSaNSWpJ6QBZSsUNjrw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiflseb2uT4AhX-LEQIHaG0BzwQ6AF6BAgCEAM#v=onepage&q=”E.%20P.%20Adams”%20″central%20pacific%20railroad”&f=false

- Edward P. Adams to Mary Baker Eddy, 27 October 1885, IC480.55.002, https://mbepapers.org/?load=480.55.002

- Edward P. Adams to Calvin A. Frye, 11 January 1886, IC938.91.006, https://mbepapers.org/?load=938.91.006

- Peter Neil Garff, “Causes of the Mormon Boycott Against Gentile Merchants in 1866 and 1868” (1971), Theses and Dissertations, 4708, https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4708https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5707&context=etd

- Catherine Armstrong, “This Tiny Utah Town has a Crazy, Wild History,” Only in Your State: Utah, Attractions, Nov. 14, 2016, https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/utah/corrine-ut-history/

- Corinne City Corp., “Corinne City History,” 2019, https://www.corinnecity.com/city-history.html

- Mary Baker Eddy to Edward P. Adams, 26 May 1886, L04332, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L04332

- Edward P. Adams to Mary Baker Eddy, 4 July 1886, IC480.55.004, https://mbepapers.org/?load=480.55.004

- Corinne City Corp., “Corinne City History,” 2019, https://www.corinnecity.com/city-history.html