From the Papers: Mary Baker Eddy, Christian Science, and the temperance movement

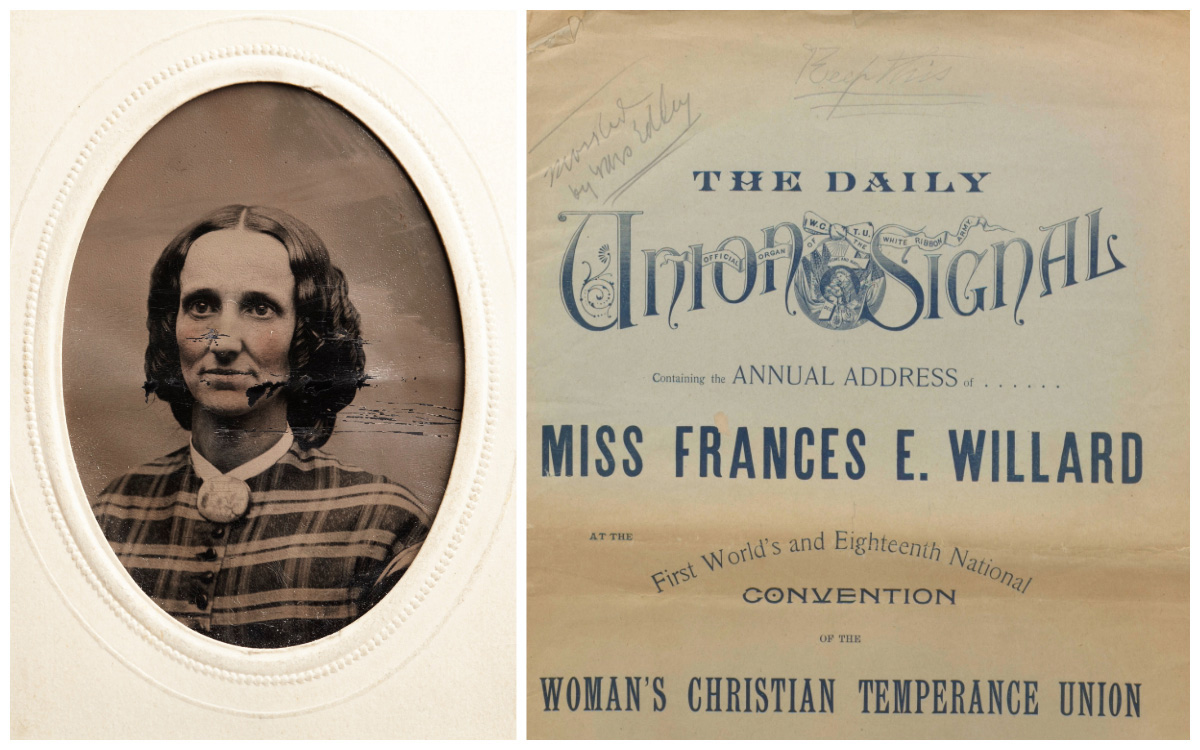

Studio portrait of Mary Baker Eddy (then Mary M. Patterson), circa 1863. P00161. Eddy’s copy of The Daily Union Signal newspaper announcing Frances Willard’s WCTU convention address in Boston, November 11–18, 1891. PE00091.

The temperance movement—a political and social cause led primarily by women—opposed the negative effects of alcohol on users and their families, as well as on the collective morality of society. It coincided chronologically with the development of Christian Science, taking shape through the 1870s and gathering momentum in the decade to follow. Some Christian Scientists also participated in the movement, including Mary Baker Eddy herself. By exploring documents included in the Mary Baker Eddy Papers, we can begin to learn more about some of these intersections.

Early efforts to regulate alcohol consumption, such as the 1812 Massachusetts Society for the Suppression of Intemperance, did not oppose alcohol itself but rather drunkenness. The ideal was therefore moderation, which is the original meaning of the word temperance.1 However, attempts to prevent inebriation through promoting moderation proved ineffective against the ready availability of cheap grain alcohol. So temperance advocates shifted their tactics to advocating total abstinence. Eddy addressed this shift in her book Miscellaneous Writings 1883–1896: “Whatever intoxicates a man, stultifies and causes him to degenerate physically and morally. Strong drink is unquestionably an evil, and evil cannot be used temperately: its slightest use is abuse; hence the only temperance is total abstinence.”2 Eddy personally signed a temperance pledge, committing herself to complete avoidance of alcohol, and advocated abstinence for her church, as “the use of tobacco or intoxicating drinks is not in harmony with Christian Science.”3

Eddy probably took her temperance pledge sometime between 1837 and 1841. In a document titled “Biography,” she described it as occurring in connection with the temperance activities of her second oldest brother, Albert Baker.4 Elected to the New Hampshire assembly in 1837, he won nomination for the state congress in 1841. Unfortunately he died before he could serve.5 Legislation that he had helped draft resulted in a state referendum on prohibition in 1848, which was implemented in 1855.6 Albert promoted temperance outside the legislative framework also. According to Eddy, he “delivered the first Temperance lecture and drew up the first Temperance pledge in the state of New Hampshire”—the very pledge that she signed.7

Eddy’s personal commitment to abstinence in about 1840 would become a public commitment some 25 years later, after she and her then-husband Daniel Patterson moved to Lynn, Massachusetts, and joined the Linwood Lodge of Good Templars.8 This was the local branch of the Independent Order of Good Templars (IOGT), founded in 1851.9 The IOGT accepted both women and men as members, in contrast to the gender-segregated Sons of Temperance and Daughters of Temperance of the 1840s,10

During her time at the Linwood Lodge, Eddy was a very active member. Edwin J. Thompson, the “worthy chief” of Linwood, later recalled that she “used to speak often at meetings, saying sensible and helpful things.”11 George Newhall, a member at that same society, likewise remembered that she “wrote and read many pieces at the meetings.”12 Eddy herself summarized her accomplishments at Linwood Lodge as having “reformed many drunkards, and rescued the Woman’s Branch of The Temple of Honor from a complete wreck, and one year added to its number seventy-five members.”13

In addition to her own work, Eddy celebrated the achievements of nearby temperance societies. In 1866 she wrote a letter to the editor, about a new hall being fitted up for Seaside Temperance Lodge.14 This may be the hall that she referred to in her poem “Dedication Hymn” as a “Temp’rance Hall.”15 She wrote another temperance poem in 1867, “Anniversary Ode”, for a lodge in Taunton, Massachusetts.16

But in February 1866, an accident interrupted Eddy’s temperance work. While walking to a meeting at the Linwood Hall,17 she fell on an icy sidewalk. Her recovery through prayer was a turning point on her path to founding Christian Science, and from then on she dedicated herself more single-mindedly to that cause. Her autobiographical work, Retrospection and Introspection, explains that after that experience she effectively “withdrew from society,” pursuing biblical research that would find expression in Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, which she first published in 1875.18

The early 1870s were also the formative years for the solidification of temperance activities into a nationwide, women-led movement. Inspired by Dr. Diocletian Lewis’s 1873 lecture “The Duty of Christian Women in the Cause of Temperance,” groups of well-dressed women would enter taverns, liquor stores, and hotels, asking the proprietors to take a pledge not to sell alcohol. If they refused, women would remain there, praying, until the proprietors complied.19 These activities became known as the “Women’s Crusade” and culminated in the 1874 formation of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU).20

While Eddy is not documented as a member of the WCTU, her personal commitment to abstinence remained unwavering. She applauded the work of the temperance movement and saw the goals of Christian Science as closely aligned with it, writing that “the cause of temperance receives a strong impulse from the cause of Christian Science: temperance and truth are allies, and their cause prospers in proportion to the spirit of Love that nerves the struggle.”21

In 1882 Eddy wrote admiringly to Clara E. Choate, in praise of both the temperance and suffrage movements (the latter also gaining momentum through the 1870s and 1880s):

It is glorious to see what the women alone are doing here for temperance. More than ever man has done. This is the period of women, they are to move and to carry all the great moral and Christian reforms, I know it. Now darling, let us work as the industrious Suffragists are at work who are getting a hearing all over the land.22

Undoubtedly the coexistence of temperance and suffrage—as well as abolition—as predominantly women-led movements was mutually beneficial; women had opportunities within these contexts to take center stage as speakers and leaders, which in turn normalized their participation in the public sphere and made it easier for other women to follow in their footsteps. The Christian Scientist women who spoke publicly and took leadership roles would have both benefited from and contributed to this.

Social reformation, aligning as a common goal of the temperance movement and Christian Science, is seen in the crossover of participants between the two causes. Because no national directory of temperance movement members exists, the following list is not exhaustive or complete. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note a few prominent examples:

- Eddy’s third husband, Asa Gilbert Eddy, was a temperance enthusiast. According to Eddy, temperance was his “favorite cause,” and he wrote to James Ackland about staying in a “temperance hotel” when they visited Philadelphia.23

- Captain John F. Linscott, who with his wife Ellen Brown Linscott spread Christian Science to Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Denver, had been a “platform speaker” for the WCTU for 10 years before devoting his attention to Christian Science.24

- Ebenezer J. Foster Eddy, adopted by Eddy as her son for a period of time, was involved with Mt. Zion Commandery, Knights Templar, “of which he has been eminent commander.”25

Other Christian Scientists who were active in the temperance movement include Mrs. M. R. Bly,26 Chloe A. S. Dow,27 Ella Peck Sweet,28 Irving C. Tomlinson,29 Harriette D. Walker,30 and Margaret A. Watts.31

Eddy’s own continued interest in the temperance movement is evidenced by the inclusion of The Daily Union Signal for 1891—the official newspaper of the WCTU—in the library of her home in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. She marked several pages in this issue and inscribed “Keep this” on the cover. 32

By 1904, however, Eddy had come to take the position that membership in other organizations was a distraction for members of her church. In June 1904 she announced a new By-law for the Manual of The Mother Church, stating that, while Christian Scientists did not need to quit “benevolent and progressive organizations, such as … temperance societies” that they already belonged to, they should not become members of additional organizations, in order to choose (as she had after her accident in 1866) to devote their attentions more single-mindedly to the “philanthropic, therapeutic, and progressive Christian work for the human race” that Christian Science advocated.33

It wasn’t that Eddy had had a change of heart about the importance of the temperance movement. Rather, she saw Christian Science as the remedy by which temperance could be achieved, convincing the drinker of the unreality of the pleasure to be had from alcohol, as “liquors lose their tempting power over the mind.”34

- W. J. Rorabaugh, Prohibition: A Concise History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 11.

- Mary Baker Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings 1883–1896 (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 288–289.

- Mary Baker Eddy, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 454.

- Eddy, “Biography,” 1903, A10219, https://mbepapers.org/?load=A10219

- Gillian Gill, Mary Baker Eddy (Cambridge: Perseus Books, 1998), 18–20.

- Robert Peel, Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Discovery 1821–1875 (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1966), 88.

- Eddy, “Biography,” https://mbepapers.org/?load=A10219

- Gill, Mary Baker Eddy, 154.

- Rorabaugh, Prohibition, 20. The IOGT took their name from the Knights Templar, a religious military order of the Catholic Church (active 1119–1312), who safeguarded travelers as they made pilgrimage to the holy city of Jerusalem and then fought in the Crusades. See “Knights Templar,” History.com, 2023, https://www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/the-knights-templar

- This sexist position led to an early clash with one of the later leaders of the suffrage movement, Susan B. Anthony. In 1852 she was prevented from speaking at a Sons of Temperance movement and consequently started her own organization, where women were permitted leadership roles and speaking opportunities, making it more popular. By 1865, the IOGT had approximately seven million members. See Ruth Bordin, Women and Temperance: The Quest for Power and Liberty, 1873–1900 (New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press, 1990), 5, and Rorabaugh, Prohibitioni, 20.

- Edwin J. Thompson to John H. Thompson, 28 January 1907, Subject File.

- George Newhall, 1920, Reminiscence, 1.

- Eddy, “Biography,” https://mbepapers.org/?load=A10219. Several of Eddy’s biographers have stated that she was named “Exalted Mistress of the Legion of Honor.” See, for example, Gill, Mary Baker Eddy, 154. The earliest source found for this claim was Robert Collyer Washburn, The Life and Times of Lydia E. Pinkham (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1931), 77. No primary sources have been found that authenticate this.

- Tamara Long, “A ‘Beautiful Residence’ in Swampscott,” Longyear Museum, 2016, https://www.longyear.org/learn/research-archive/swampscott-ad-1866/

- Eddy, “Dedication Hymn,” n.d., A10013. https://mbepapers.org/?load=A10013. This was later revised and published in Eddy’s book Poems (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors, 1910), 39.

- Eddy, “Anniversary Ode,” 17 July 1867, A10011. https://mbepapers.org/?load=A10011

- Sources disagree as to whether the accident occurred on the way to or from the meeting.

- Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 27.

- Bordin, Women and Temperance,15–16, 19–33.

- Rorabaugh, Temperance, 26–27.

- Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings, 288–289.

- Eddy to Clara E. Choate, 15 March 1882, L04088. https://mbepapers.org/?load=L04088

- Eddy, Statement Regarding the Passing of Asa Gilbert Eddy, 1882, A10213B. https://mbepapers.org/?load=A10213B; Asa Gilbert Eddy to James Ackland, 18 February 1882, L16162. https://mbepapers.org/?load=L16162

- John F. Linscott to Eddy, 30 November 1886, 164AP1.28.001. https://mbepapers.org/?load=164AP1.28.001. See also Linscott to Joshua F. Bailey, 30 April 1889, 164AP1.28.019. https://mbepapers.org/?load=164AP1.28.019

- William Richard Cutter, New England Families, Genealogical and Memorial: A Record of the Achievements of Her People in the Making of Commonwealths and the Founding of a Nation (New York: Lewis Historical Pub. Co., 1913), 4.

- Mrs M. R. Bly to Eddy, 11 December 1888, 648B.67.036. https://mbepapers.org/?load=648B.67.036

- Chloe Anna Smith Dow was president of the WCTU in Crawford County, Iowa. See “Mrs. Chloe Anna Smith Dow,” The Christian Science Journal, June 1887, 149, https://journal.christianscience.com/issues/1887/6/5-3/mrs.-chloe-anna-smith-dow

- Marylee Hursh, “Ella Peck Sweet, C.S.D.,” The Longyear Museum, 1981, https://www.longyear.org/learn/research-archive/ella-sweets-pioneer-work-in-colorado/

- Irving C. Tomlinson’s mother was one of the founders of the WCTU and Eddy wrote to him about attending a temperance meeting. See Michael Meehan, Mrs. Eddy and the Late Suit in Equity (Cambridge: University Press, 1908), 346; Eddy to Irving C. Tomlinson, 1899, L03671. https://mbepapers.org/?load=L03671

- Harriette D. Walker, a delegate of the Rhode Island Women’s Christian Temperance Union, wished to study with Eddy. See Harriette D. Walker to Eddy, 21 October 1885, 721AP1.88.029, https://mbepapers.org/?load=721AP1.88.029

- Margaret A. Watts was the Louisville delegate to the National WCTU in 1891. See Margaret A. Watts to Eddy, 25 November 1891, 584.60.005. https://mbepapers.org/?load=584.60.005

- See The Daily Union Signal containing the Annual Address of Miss Frances E. Willard at the First World’s and Eighteenth National Convention of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union Held in Boston November 11–18, 1891, PE00091.

- Eddy, “Take Notice,” Journal, June 1904, 184, https://journal.christianscience.com/issues/1904/6/22-3/take-notice. Eventually Eddy decided to remove mention of specific organizations in that By-Law. And she included a statement that Mother Church members should “not unite with organizations which impede their progress in Christian Science,” as well as pointing out to members that “within the wide channels of The Mother Church” they had a “dutiful and sufficient occupation.” See Eddy, Church Manual (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 44–45.

- Eddy, Science and Health, 404; Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings, 297.