From the Papers: The Chicago institutes

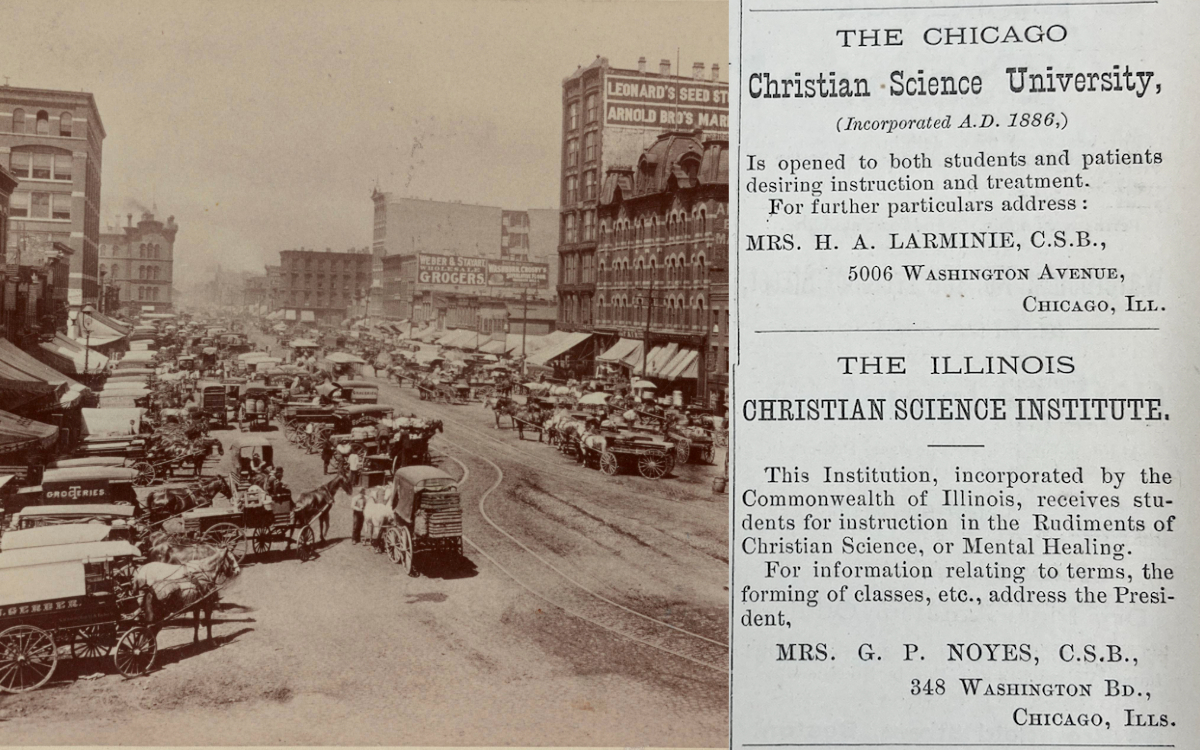

Views of Chicago, Haymarket Square, c. 1889–1910. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ds-14205. Notices in The Christian Science Journal, September 1886.

In the middle of 1886, the subject of forming Christian Science institutes was a primary topic of correspondence between Mary Baker Eddy and her students. Past articles in this series have documented aspects of this.1 The purpose of these institutes was to give Christian Science greater visibility in major cities and prevent confusion about where the public could receive accurate teaching in Eddy’s new system of healing.

Chicago presented a particularly interesting case. The city was growing rapidly. A significant number of Eddy’s students were located there. Moreover, it embodied “‘the concentrated essence of Americanism,’” as a hub of capitalism and innovation, alongside organized labor and social movements.2

As our Papers team continues to learn, Eddy’s correspondence with her Chicago students about opening institutes shows the evolution of Christian Science alongside this dynamic city. Ideas were proposed in letters, sometimes tested, or dropped just as quickly. Eddy and her students were figuring out the best way to ground Christian Science on a solid foundation. An examination of the correspondence from the summer of 1886 sheds light on their exchange of ideas.

On May 26, 1886, when Eddy invited her students to open institutes,3 Chicago was only a few weeks past the “Haymarket affair”—a violent confrontation between police and attendees at a May 4 labor rally, following an incident between police, striking workers, and strikebreakers at the McCormick Machine Harvesting Company the day before.4 Additional strikes had been happening in the city in support of an eight-hour workday.5

M. Bettie Bell referred to the situation when responding to a letter from Eddy about why she hadn’t been able to attend her last class: “At time I received notice our house was full of men papering- painting &c- then came the strikes in oneur City & left the work unfinished & my Husband thought it not best for me to go under Circumstances .…” 6 Although the situation doesn’t receive further mention in Eddy’s correspondence, she would surely have been aware of it when considering the need for leadership in Chicago.

Even before Eddy sent her students that official directive to open institutes, she was discussing the qualities an institute’s leader should possess. On March 5 she wrote to Ellen Brown Linscott, “I want a learned Teacher, and a firm, honest character to take the head of a Chicago Institute.”7 On June 7 she reiterated the point, after the call to open institutes had been sent: “… establish an Institute of Christian Science in Chicago as soon as possible but get an educated Teacher for it.”8 Then on June 10 she expressed the same sentiment to George B. Day: “I do not approve of starting the first C.S. Institute in Chicago without having at its head a teacher with a liberal education not all the or or sufficiently scholarly to bear inspection, — and strictly scientific”9

Eddy had also discussed the need for an educated teacher with her student Hannah A. Larminie, writing to her on June 3, “Chicage is where I want the School planted, and it must be – God has said it; and named Science ‘Metaphysical Science College’ this needs to be done at once.”10 In response, Larminie offered a possible answer. She proposed securing her brother-in-law, Matthew Clarke, as president of a Chicago institute. At the time he was president of the Norfolk Mission College, a school for African American students in Virginia. Of Mr. Clarke she wrote:

… he is a Presbyterian minister, thoroughly educated– understands Greek– Hebrew and Latin– good preacher and a splendid teacher– about Sixty years old– well preserved, and of Scotch decent – therefore a little conservative ….11

There was only one problem: Clarke was not a student of Christian Science. Larminie was nonetheless optimistic that he might become one, and a letter from Clarke to Eddy indicated that he did have some interest.12 Eddy supported the idea, inquiring to Larminie on June 23: “Will you and your sister’s husband open an Institute will he join my class if I have one sooner than Sept or are you going to teach him?”13

The idea appears to have been dropped; it doesn’t come up in any further correspondence, and Larminie and Clarke never opened an institute together. However, it shows the more experimental approach to organizational structures that permeated the movement at this time. While it may have been clear to Eddy that institutes were needed to promote the teaching of genuine Christian Science, what exactly they should look like, and who should lead them, was still evolving.

It is possible that Eddy felt the leader of an institute needed to be educated in order to counter the other healing modalities that were opening competing schools in Chicago—and creating confusion about Christian Science. Day mentioned it to Eddy in his first response to the idea of institutes:

I have given your note urging the establishment of an Institute, particular attention. There are two Mesmeric Schools already started. One by Schwarz, another by a Mr. Charles– the latter of which is incorporated as I learn by report.14

Ursula Gestefeld echoed a similar sentiment:

So far as the general public is concerned, there is little discrimination between the different methods of mental healing now presented; Institutes, colleges and schools are cropping out all over the country. Here in Chicago are a number….

Gestefeld’s proposed answer was to have a single institute in Chicago, to make clear that Christian Science institutes weren’t the individual efforts of one charismatic person but rather “a collective, united, concentrated force and strength, instead of a personal one in different directions.” Most importantly, she felt that it “would place ‘Christian Science’ before those who are unable to distinguish between it and other methods, at the head of all.”15

Prior to this, Eddy had suggested that her students in Chicago join together to form a “Teachers’ Society,” each with their own institute, four in total.16 However, it appears that her thought had been moving the same direction as Gestefeld’s, at least on this topic. She responded the next day: “Yours received, I had given my directions to a student before receiving your letter – very nearly in accord with it. I like union, it is strength.”17

Who was to work together—and how? On August 8, 1886, Eddy wrote to Day:

I propose for the leading ones President and other heads of departments Rev. Mr. Day, Mrs Day, Mrs. Larmine, Bell [?] Mr. B. Sherman Mrs. Bell – and Miss Brown will be a good auxiliary [?] Please consider this letter strictly confidential. I have no favorits in students, I love them all, but I want the Christians who have had Christian experience to take the lead in this mattter….18

However, there were issues of both personality and location standing in the way. Silas J. Sawyer, who had been assisting several of Eddy’s students with setting up institutes, described the challenges. On the topic of personality, he wrote of Day:

After service I had a long talk with Rev Day, about the “Institute”. I regret to say I find in him, a lack of energy, also a timidity. in relation to trusting to Science. He remarked that he could not see his way clear, how to conduct such an institution, especially where so many were interested.19

Sawyer also described personality conflicts between Ellen Brown Linscott and other students. He indicated that Bell’s husband would not allow her to join together with Brown Linscott to form an institute. He also expressed concerns about location, due to Chicago’s growing size:

… Now let me give you Mrs Bell and Larminie’s situation.

They both live in Hyde Park. which is a long distance from all the others; also Hyde Park is the wealthiest, and largest township attached to the City. Mrs Larminie offers her home for use as an Institute. Mr Day thinks it ought to be up in the business part of City. that, will be very expensive though.20

While much of the conversation in the correspondence revolved around the same individuals, alongside all of this was Caroline D. Noyes, another of Eddy’s Chicago students, who was the first to set up her own institute. Even though Eddy was encouraging other students to work together, she seems to have supported Noyes in her solo effort. She wrote to Noyes on July 28: “Do as you please dear about going on with starting an Institute.”21 Noyes’s institute was the first one advertised in the Chicago area, appearing in the August 1886 issue of The Christian Science Journal as the “Illinois Christian Science Institute.” In the following months, many of the other individuals named in this article went on to start, or join with others in starting, Christian Science institutes around the city.

It is notable that alongside the establishment of Christian Science institutes, Eddy’s students in Chicago also started holding church services and incorporated a Church of Christ, Scientist, on June 13, 1886. Church services would provide another important opportunity for the public to learn more about Christian Science.

Eddy’s correspondence with her Chicago students in the summer of 1886 shows how her young movement was still in a period of exploration and experimentation. She was providing direction to them, while at the same time listening to their thoughts and concerns, as they worked together to establish Christian Science in a city of rapidly expanding influence. You can learn more about all of these individuals by reading their short biographies on the Papers site.

Please note: Quoted references in our From the Papers article series reflect the original documents. For this reason they may include spelling mistakes and edits made by the authors. In instances where a mark or edit is not easily represented in quoted text, an omission or insertion may be made silently.

- See https://www.marybakereddylibrary.org/research/open-a-public-institute-at-once/ and https://www.marybakereddylibrary.org/research/from-the-papers-women-practicing-christian-science-in-the-american-west/

- Donald L. Miller, City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996), 188.

- Eddy sent copies of the same letter to a number of students. See for example Eddy to Hannah A. Larminie, 26 May 1886, L04477.

- See “Haymarket Affair,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 15 March 2024, https://www.britannica.com/event/Haymarket-Affair.

- See Richard Schneirov, “The Haymarket Bomb in Historical Context,” 2016, https://digital.lib.niu.edu/illinois/gildedage/haymarket.

- M. Bettie Bell to Eddy, 8 May 1886, 020A.09.010, https://mbepapers.org/?load=020A.09.010.

- Eddy to Ellen Brown Linscott, 5 March 1886, L11003, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L11003.

- Eddy to Linscott, 7 June 1886, L11004, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L11004.

- Eddy to George B. Day, 10 June 1886, L14721, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L14721.

- Eddy to Larminie, 3 June 1886, L04479, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L04479.

- Larminie to Eddy, 8 June 1886, 295.42.008, https://mbepapers.org/?load=295.42.008.

- Matthew Clarke to Eddy, 18 June 1886, 657B.69.016, https://mbepapers.org/?load=657B.69.016.

- Eddy to Larminie, 23 June 1886, L04480, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L04480.

- Day to Eddy, 7 June 1886, 060A.17.006, https://mbepapers.org/?load=060A.17.006.

- Ursula N. Gestefeld to Eddy, 27 July 1886, 544.57.006, https://mbepapers.org/?load=544.57.006.

- See Eddy to Larminie, 13 July 1886, L04481, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L04481.

- Eddy to Gestefeld, 28 July 1886, L12898, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L12898.

- Eddy to Day, 8 August 1886, L14723, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L14723.

- Silas J. Sawyer to Eddy, 15 August 1886, 237AP2.38.030, https://mbepapers.org/?load=237AP2.38.030

- Sawyer to Eddy, 15 August 1886, 237AP2.38.030, https://mbepapers.org/?load=237AP2.38.030.

- Eddy to Caroline D. Noyes, 28 July 1886, L05421, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L05421.