From the Papers: Publishing the Frye account books

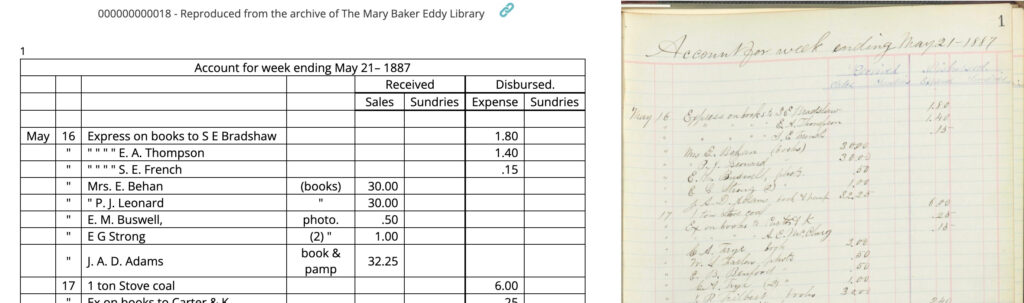

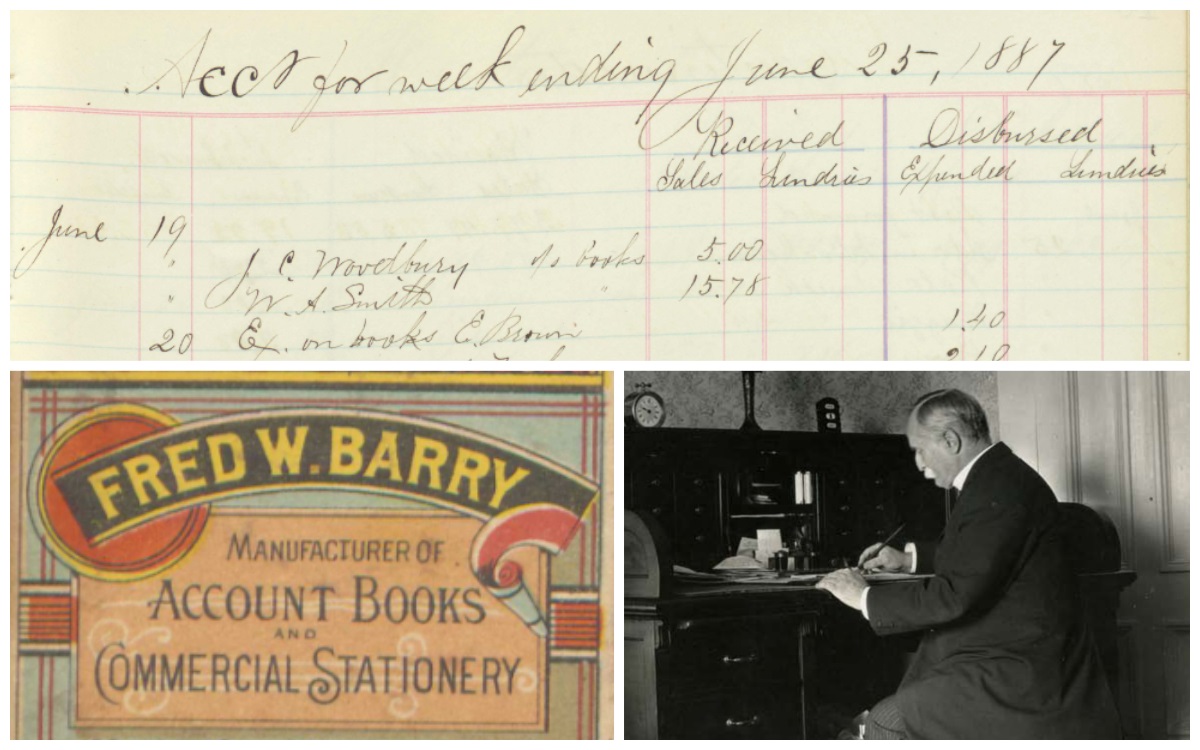

Page and inside front cover from Calvin A. Frye’s account book, 1887–1891. Calvin A. Frye, photo by Minnie B. Weygandt, P00724.

Strawberries, stamps, and salt cod. Fish bills, express shipping, and copyright fees. Sometimes the more mundane records in the Library’s collections can provide the most fascinating windows into Mary Baker Eddy’s working households.

Entries for all of these expenses—along with wages paid and income from sales of Eddy’s books, among other transactions—were all meticulously recorded by Eddy’s longest-serving employee, Calvin A. Frye. The Library previously featured the article ”Calvin Frye’s account books.” Now we’re bringing these ledgers of expenses and disbursements to your attention again, to let you know that the Mary Baker Eddy Papers has begun publishing these bound volumes, and to show how you can view them online.

A few broad categories of books make up Frye’s financial records. Checkbooks, similar to those used today, span the years 1898 to 1914 (Frye continued to use them for the household’s expenses after Eddy’s passing in 1910). They contain either just stubs recording used checks or both the stubs and unused checks. There are some smaller ledger books, as well as small notebooks recording deposits. The ones that the Papers team is tackling first are ledger-/legal-sized account books, in which Frye recorded amounts of money received and disbursed. The household entries contained in these ledgers date from 1887 to 1910 and provide line-by-line insights into the daily activities at Eddy’s homes in Boston, Massachusetts; Concord, New Hampshire; and Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts.

The Papers team has begun the process of publishing Frye’s account books by starting with the first one, which begins on May 16, 1887, and contains entries through April 25, 1891.

On our Papers website you can read a transcription of the ledger and see a scan of the book itself, just as is the case with Eddy’s correspondence.

On May 16, 1887—the first day of his entries—Frye recorded names of Eddy’s students who had bought her textbook of Christian Science, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, which they would then have resold as part of their public healing practices. He included the amounts received. It’s worth noting that Eddy’s correspondence documents a high demand for the book, with students often ordering a dozen copies at a time. Expenses for the day included amounts paid for a photograph of Eddy and for copies of a pamphlet, as well as express shipping charges for copies of Science and Health. The following day we see an expense for one ton of stove coal. It is important to note that $1.00 in 1887 is equal to $33.14 in 2024—meaning that ton of coal would cost $198.84 today.1

On our website you can read Frye’s account ledgers by scrolling through the text, or jump to a specific date using the Scroll to page feature:

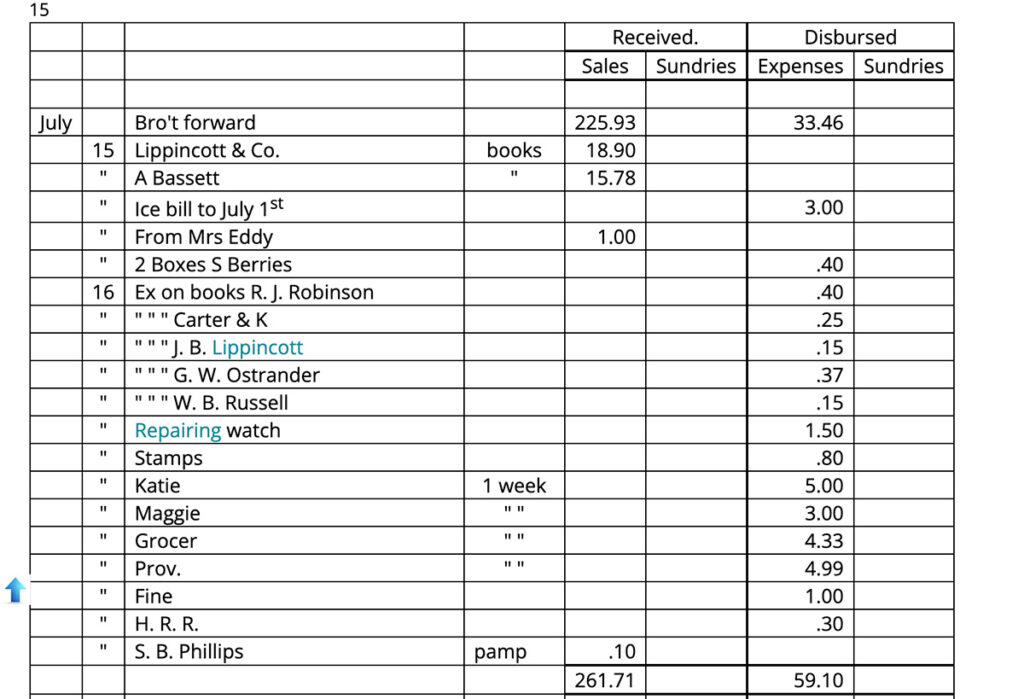

Beginning with entries for July 15, 1887, for example, expenses included ice, strawberries, stamps, and a watch repair over that and the next day.

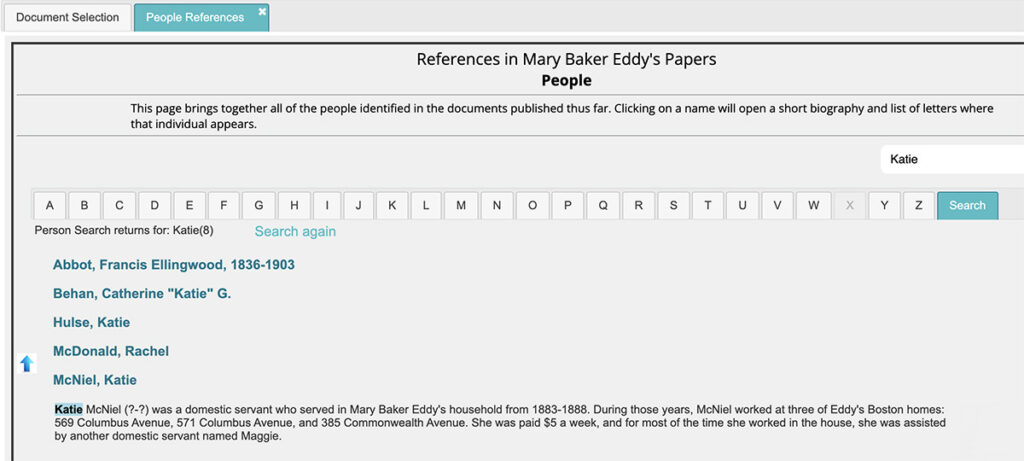

Household employees Katie and Maggie each received their weekly wages. While we have not yet learned anything more about Maggie, you can find a biographical sketch for Katie McNiel on our People Reference List. She worked in three of Eddy’s Boston homes between 1883 and 1888. Maggie assisted her with domestic chores. It was through matching these account records with mentions of Katie in Eddy’s correspondence that we were able to determine her role and establish her identity.

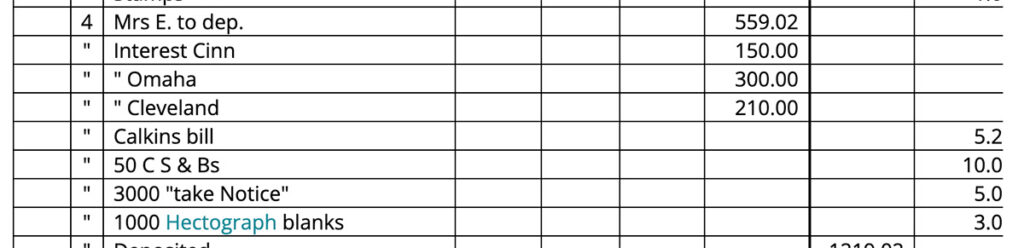

Entries from July 1 and August 4 list “Hectograph” and “1000 Hectograph blanks.” These reveal Frye’s use of a copying technology that involved writing on a special transfer paper, in order to create a document that was then pressed into a pan of gelatin. The ink would remain on the surface of the gelatin and a blank piece of paper could then be pressed down on it to create a copy. The term hectograph implied that one could make 100 copies before starting over with a new master.

We’ve just begun working on Frye’s account books, and we have a long way to go in annotating them. But we hope you enjoy looking at these important records and exploring all that they reveal about life and work in Mary Baker Eddy’s homes, ways she earned income from her writings, and how the Christian Science movement grew over time.

Please note: Quoted references in our “From the Papers” article series reflect the original documents. For this reason they may include spelling mistakes and edits made by the authors. In instances where a mark or edit is not easily represented in quoted text, a deletion or insertion may be made silently.