(Updated September 22, 2024)

When Calvin A. Frye joined Mary Baker Eddy’s staff on August 14, 1882, he was a 36-year-old widower who had been working as a machinist in Lawrence, Massachusetts. He would remain with Eddy until her passing in 1910, serving as “a combination of secretary, accountant, household manager, and social organizer,” as biographer Gillian Gill described him in her 1998 book Mary Baker Eddy. Frye was a constant presence in Eddy’s life, a quiet, humble man, deeply devoted both to her and to the cause of Christian Science.

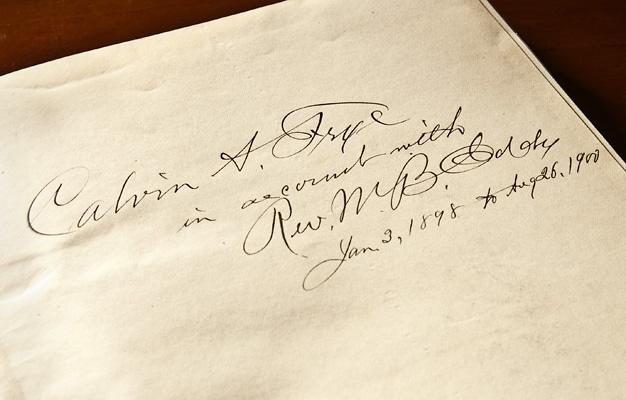

Frye had a meticulous, exacting mind and he left extensive records of his work with Eddy and her staff. Among the collections of The Mary Baker Eddy Library are six boxes of financial record books that he kept, dating from 1886 to 1917. Frye used account books, bank books, ledger books, and checkbooks, each serving a different purpose and recording the credits and debits to Eddy’s accounts—from purchases of a few pennies up to thousands of dollars in income. After her passing, he kept track of the expenses for the caretakers at her Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, home for a few years, and also kept track of his own personal expenditures.

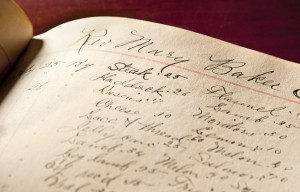

The household accounts are complete from 1898 to 1910 and provide a wonderful glimpse into the daily life at Eddy’s homes in Concord, New Hampshire (named Pleasant View) and Chestnut Hill. One way to look into these books is by taking a snapshot of one moment in time. For, example, we can see that in a typical week at Pleasant View—beginning Sunday, July 23, 1899—the first expense was for groceries, on Tuesday, July 25. Someone—probably Minnie Weygandt, serving at that time as Eddy’s cook—purchased steak ($0.25), flannel cloth ($0.25), haddock ($0.26), and lamb ($0.35).

Two things are immediately apparent about grocery purchases. The first involves the rate of inflation and the frequency and variety of purchases. Food appears comparatively less expensive in 1899 than today. Even when the amount is adjusted, 25 cents would not buy a lot of steak at today’s prices! In fact, the sum total of food purchases for that week in 1899 came to $8.92. According to an inflation calculator, that would be about $338.00 in 2024. Also, we don’t know how many pounds of steak or lamb were purchased, for Frye only rarely recorded the quantities of items. But we do know that Pleasant View in 1899 was not a small household—so they were probably buying at least several pounds at a time.

The frequency of food purchases is also interesting. With little-to-no facility for preserving the food that was purchased, Weygandt or someone like her was venturing out nearly every day to buy fresh ingredients for meals. It is also worth considering that Pleasant View was a working farm with a thriving vegetable garden; therefore the household was eating far more than is reflected in Frye’s account books, as they were purchasing what they could not grow or raise themselves. For example, in that same week in 1899, Frye recorded these purchases:

Tuesday—steak, haddock, lamb

Wednesday—raisins, cheese, lemons, melon, salmon, lamb, and squash

Thursday—leg of lamb, fruit, veal, codfish, cheese, steamer (clams)

Friday—veal, plums, melon, oranges, pears, berries, blueberries, butter

Saturday—eggs

In that same week, Frye also recorded wage payments for four household workers (Mary Weygandt, Minnie Weygandt, Clara Shannon, and himself); the receipt of five telegrams; subscription payments to several magazines and newspapers; and purchases of household items such as toilet paper, lace, jelly jars, and beet seed.

Frye used slightly different accounting systems at different times. In July 1899, the left-hand pages were for debits and the right-hand for credits, with each week reconciled on the bottom-right of the right-hand page. He further divided credits into a miscellaneous column, and into one that he labeled “Family” and used for household expenses. He recorded expenses and income in pen, and then went back and reconciled accounts in pencil.

Although these account books are the most common and comprehensive of the financial record books that Frye kept, they are by no means our only look at his recordkeeping. He also balanced checkbooks at several different banks and recorded all bank deposits. Everything is carefully noted in his neat cursive script, providing a wonderful window into the seemingly mundane details and inner workings of Eddy’s households. You, too, can examine these records if you visit us at the Library—they are available for researchers to view at any time.