From the Papers: Mary Baker Eddy’s convictions on slavery

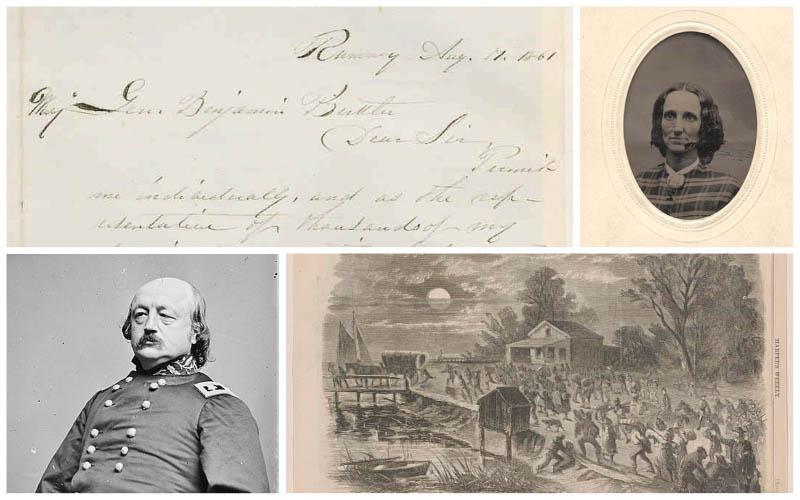

Mary Baker Eddy to Benjamin F. Butler, August 17, 1861, L02683. Studio portrait of Mary M. Patterson (Eddy), circa 1863, Tintype, Unidentified photographer, P00161. Portrait of Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, officer of the Federal Army, Brady’s National Photographic Portrait Galleries, photographer, 1861–1865, Library of Congress. Illustration of enslaved people crossing to Fort Monroe, from Harper’s Weekly, v. 5, no. 242 (1861 August 17), p. 524, Library of Congress.

https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2018666400/

https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/92515012/

The Mary Baker Eddy Papers project draws on a vast collection of letters and documents. These help show how Mary Baker Eddy and her followers engaged with the world around them. An 1861 letter from Eddy to Major General Benjamin F. Butler reveals new perspectives on her attitude toward slavery during the Civil War.

On August 17, 1861, Eddy wrote to Butler, the Massachusetts lawyer serving as a Union Army General: “Permit me individually, and as a representative of thousands of my sex in your native State– to tender the homage and gratitude due to one of her noblest Sons, who so bravely vindicated the claims of humanity.”1 The purpose of Eddy’s letter was to thank Butler for the stance he had taken in defending the freedoms of runaway slaves who had found refuge in Union territory. A deeper inquiry into her correspondence with Butler, and his role in defending the rights of Black men and women, places Eddy within a broader national conversation around slavery, property, and the Civil War.

On May 23, 1861, Frank Baker, Shepard Mallory, and James Townsend rowed across the James River in Virginia and landed at Union-held Fort Monroe to claim asylum. The three enslaved Black men were field hands who had been pressed by local Confederates into service, building an artillery emplacement in the dunes across the harbor. After learning that their master, Colonel Charles Mallory, planned to send them further from home to build fortifications in North Carolina, the young men had made arrangements to flee to the Union forces across the river.2

As commander of the fort, Butler had only arrived a day ahead of the fugitive slaves, and as a Democrat lawyer from Massachusetts was far from the abolitionist champion the men likely hoped to encounter. Nevertheless, he wrote to Lieutenant General Winfield Scott in defense of not returning the three men to their Confederate masters. Butler claimed that he “had so taken them as I would for any other property of a private citizen which the exigencies of the service seemed to require to be taken by me, and especially property that was designed, adapted, and about to be used against the United States.”3 Butler argued that the Confederates’ use of the men against the Union Army entitled him to claim them as contraband of war. He persisted in arguing that the Fugitive-Slave Act could not be appealed to in this instance, because the “fugitive-slave act did not affect a foreign country which Virginia claimed to be.”4

Simon Cameron, the Secretary of War, responded to Butler’s inquiry, affirming his actions and instructing him to prevent the continued building of enemy fortifications, by refraining “from surrendering to alleged masters any persons who may come within your lines.”5 Thus, Butler’s characterization of runaway slaves as enemy property—and therefore contraband of war—became a precedent for the treatment of runaway slaves.

The conversation continued into the fall of 1861, when Butler wrote to Cameron again, to further inquire about the women and children who had taken refuge within Fort Monroe after the troops evacuated Hampton, Virginia. They included “a large number of negroes, composed, in a great measure, of women and children of the men who had fled thither within my lines for protection, who had escaped from marauding parties of rebels who had been gathering up able-bodied blacks to aid them in constructing their batteries on the James and York Rivers.”6 Having employed the former slaves himself to build entrenchments, Butler praised them for “working zealously and efficiently at that duty, saving our soldiers from that labor, under the gleam of the mid-day sun.”

At the same time, “the women were earning substantially their own subsistence in washing, marketing and taking care of the clothes of the soldiers.” But now that the number of runaway slaves had reached 900—some 600 of them women, children, and men beyond working age—Butler was once again faced with the legal implications of harboring them in Fort Monroe. While he had claimed that enslaved working men employed in building Confederate fortifications could be considered contraband of war, he questioned this as justification for not returning enslaved women and children. On July 30, 1861, he asked his superiors:

Are they property? If they were so they have been left by their masters and owners, deserted, thrown away, abandoned, like the wrecked vessel upon the ocean. Their former possessors and owners have causelessly, traitorously, rebelliously, and, to carry out the figure practically abandoned them to be swallowed up by the Winter storm of starvation. If property, do they not become the property of the salvors?

Butler argued that if under the United States Constitution, and according to the insistence of Confederates, enslaved Black men and women were the property of their owners, then once the Confederate Army abandoned them, they would become the property of the Union Army that had saved them. Yet Butler and his soldiers opposed accepting human property. Therefore if their new owners renounced claims to ownership, the former slaves should be free. Butler continued:

But we, their salvors, do not need and will not hold such property, and will assume no such ownership. Has not therefore, all proprietary relation ceased? Have they not become thereupon men, women and children? No longer under ownership of any kind, the fearful relicts of fugitive masters, have they not by their masters’ acts and the state of war assumed the condition, which we hold to be the normal one, of those made in God’s image? Is not every constitutional, legal and moral requirement, as well to the runaway master as their relinquished slaves thus answered?7

When The New York Times published Butler’s letter on August 6, 1861, his words and actions encountered a wide range of responses. The Boston Evening Transcript praised his adroit manipulation of Southern property claims as “almost a stroke of genius,” while the Atlantic Monthly believed it was “inspired by good sense and humanity alike.”8 Yet radical Republicans saw the immediate victory for the runaway slaves as clouded by their continued identification as property.

Eddy joined the conversation on August 17, 1861, writing directly to Butler, in response to his July 30 letter, which she likely read in the Times or another paper that had also picked up the story. She praised his stance in the harboring of Black men, women, and children at Fort Monroe. She thanked him for vindicating “the claims of humanity in your late letter to Sec. Cameron”—and daring to defend “our Country’s honor, the true position of justice and equity.”9 She agreed with Butler’s views, writing: “You, as we all, hold freedom to be the normal condition of those made in God’s image.” And she closed by encouraging Butler to persevere in his fight: “The red strife between right and wrong can only be fierce, it cannot be long, and victory on the side of immutable justice will be well worth its cost. Give us in the field or forum a brave Ben Butler and our Country is saved.”

Eddy’s response to Butler’s August 6 letter highlights her support for granting the rights of humanity to all “black as well as white, men, women & children” within the United States. At a time when many Union supporters did not necessarily oppose slavery, Eddy did. While some abolitionists saw Butler’s measures as dangerous, in labeling Black men and women as property in exchange for their freedom, and spoke out against his approach, Eddy supported his actions and his affirmation of their humanity.

Butler’s July 30 letter would eventually result in the First Confiscation Act, passed on August 6, 1861. Two days later, Cameron wrote to Butler, outlining its central tenets and approving Butler’s recent appeal. The question became more difficult in the case of those escaping from masters loyal to the US government; Butler was instructed to keep detailed records, with names and descriptions of the former slaves and their masters. “Upon the return of peace,” Cameron wrote, “Congress will doubtless properly provide for all the persons thus received into the service of the Union and for just compensation to loyal masters.”10 Paradoxically, Butler’s argument, and the legislation based on it, used the status of slaves as legal property to argue for their freedom.

Many saw the new act as a victory against slavery and a move toward strengthening the Union. Others considered its affirmation of enslaved individuals as chattel a move backwards. Frederick Douglass denounced the act as not going far enough, believing its eventual significance hinged on Lincoln’s enforcement of the law.11 Other ardent abolitionists viewed the underlying structure of Butler’s policy as offensive to the moral argument against slavery, based on the equality of Black and white individuals before God.

Eddy’s letter to Butler sheds light on her anti-slavery convictions and on her willingness to advocate for them. While it is not clear if Eddy agreed with the legal basis of Butler’s reasoning, she clearly supported his conclusions that “we all, hold freedom to be the normal condition of those made in God’s image.”12

For more on this topic, read the “From the Papers” article “Mary Baker Eddy’s support for emancipation.”

- Mary Baker Eddy to Benjamin F. Butler, 17 August 1861, L02683, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L02683

- Adam Goodheard, “How Slavery Really Ended in America,” The New York Times Magazine, 1 April 2011.

- Benjamin F. Butler to Major-General to Lieutenant General Winfield Scott, 24 May 1861, in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation Of The Official Records Of The Union And Confederate Armies (1894). Series II, Vol. I. Prisoners of War, Etc.: Military Treatment of Captured And Fugitive Slaves.

- ibid.

- Simon Cameron, Secretary of War to Major-General Butler, 30 May 1861, in The War Of The Rebellion: A Compilation Of The Official Records Of The Union And Confederate Armies (1894), Series II, Vol I. Prisoners of War, Etc.: Military Treatment Of Captured And Fugitive Slaves.

- “The Slave Question.” Letter from Major-Gen. Butler on the Treatment of Fugitive Slaves. Headquarters Department of Virginia Fortress Monroe, 30 July 1861, in The New York Times, 6 August 1861.

- Ibid.

- Boston Evening Transcript, 7 September 1861; “The Contraband at Fortress Monroe,” Atlantic Monthly, November 1861, 630.

- Mary Baker Eddy to Benjamin F. Butler, 17 August 1861, L02683, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L02683

- Simon Cameron, Secretary of War to Maj. Gen. B. F. Butler, 8 August 1861, in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation Of The Official Records Of The Union And Confederate Armies (1894). Series II, Vol. I. Prisoners of War, Etc.: Military Treatment of Captured And Fugitive Slaves.

- Ed. Frederick Douglass, “The Confiscation and Emancipation Law,” Douglas Monthly, Rochester, New York, August 1862.

- Mary Baker Eddy to Benjamin F. Butler, 17 August 1861, L02683, https://mbepapers.org/?load=L02683