From the Papers: Mary Baker Eddy’s support for emancipation

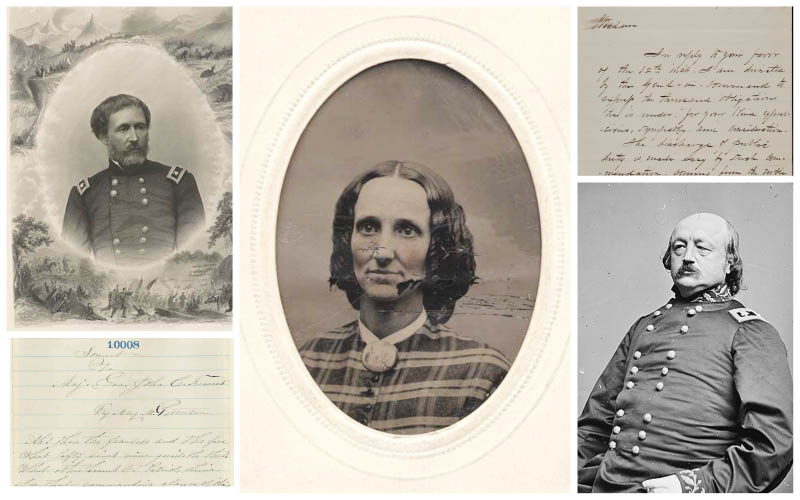

Portrait of John C. Fremont, circa 1862–1864, by William Momberger. Courtesy of Library of Congress; Sonnet, 1861, Mary Baker Eddy, December 13, 1861, A10008; Tintype studio portrait of Mary Baker Eddy, circa 1863, unidentified photographer, P00161; Peter Haggerty to Mary Baker Eddy, August 20, 1861, 653.68.026; Portrait of Major General Benjamin F. Butler, circa 1861–1865, by Brady’s National Portrait Galleries, Courtesy Library of Congress.

Last September’s “From the Papers” article—”Mary Baker Eddy’s convictions on slavery“—explored Mary Baker Eddy’s correspondence with General Benjamin F. Butler, offering a window into her views on slavery. Writing to Butler in August 1861, she affirmed a significant claim Butler had made—that runaway enslaved workers, who had taken refuge at Fort Monroe, Virginia, were contraband of war and thus free, not to be returned to their former Confederate masters.

Since the publication of that article, the Mary Baker Eddy Papers team has made new discoveries on this topic. One of the most notable is a letter that Butler’s Aide de Camp, P. H. Haggerty, wrote to her on August 20, 1861, saying he was “directed by the General in command to express the thousand obligations he is under for your kind expressions, sympathy, and consideration.” Haggerty continued, “The discharge of public duty is made easy by such commendations, coming from the noble and loyal of the land.”1

Eddy later recorded that her efforts in support of Butler did not end with her first letter to him. Encouraging further endorsement, she drafted a petition and collected the signatures of other women who aligned with the cause of emancipation.2 Further, Eddy’s interest moved beyond her correspondence with Butler. As news spread of his successful claim throughout the Union Army, she closely followed the ramifications. When General John C. Frémont, commander of the Union Army of the West, acted in response to Butler’s success, Eddy wrote a poem describing him as one of the “fearless and the free.” She reflected on his efforts and proclaimed her continuing interest in the cause of emancipation.

As the Civil War persisted, Eddy’s writings carefully traced the pursuit of freedom for enslaved African Americans, and she recognized the actions of Union commanders who followed Butler’s example. Through letters and poetry, she advocated for emancipation and reflected on its advancement, showing special interest in how Butler’s move against slavery was setting off further attempts to overturn the institution through military action.

Perhaps emboldened by Butler’s recent success, Frémont issued a proclamation on August 30, 1861, that instituted martial law in the state of Missouri. This included the confiscation of Confederate property and the freeing of enslaved men and women owned by rebel Missourians. However, Frémont’s attempt to weaken the Confederacy there through targeting slavery was far from successful, in comparison with Butler’s victorious efforts in Virginia.

Before receiving his appointment as major general of the Union troops in Missouri, Frémont had explored the American West, helped to secure California as the thirty-first state, profited from the subsequent Gold Rush, and served as both a military governor and California state senator. He had also experienced setbacks that included defeat in a run for the 1856 presidential election and a court-martial for mutiny, disobedience, and conduct prejudicial to military dismissal, following his short tenure as military governor of California. President James K. Polk eventually dismissed his penalties, and Frémont resigned from the army.

When Frémont arrived in St. Louis in July of 1861, having recently been reinstated in the military, the city was already torn by sectional loyalties. Shortages in manpower, materials, and finances did not make matters easier. He wrote to President Abraham Lincoln on July 30, explaining gains the Confederate army had been making: “I have found this command in disorder, nearly every county in an insurrectionary condition, and the enemy advancing in force by different points of the southern frontier.3 When conditions did not improve, and Union General Nathaniel Lyon’s army was defeated at Wilson’s Creek on August 10, Frémont issued a proclamation on August 30, 1861:

In order, therefore, to suppress disorder, to maintain as far as now practicable the public peace, and to give security and protection to the person and property of loyal citizens, I do hereby extend and declare established martial law throughout the State of Missouri.4

Frémont proclaimed that those who entered Missouri with arms would be tried by court-martial and shot if found guilty, and “the property, real and personal, of all persons in the State of Missouri who shall take up arms against the United States, or who shall be directly proven to have taken an active part with their enemies in the field” was “declared to be confiscated to the public use.” Most controversial was the order that “their slaves, if any they have, are hereby declared freemen.”5 Confederates in Missouri were alarmed by the edict and attempted to take measures to preserve their slave ownership and protect their property. Nevertheless some enslaved workers quickly sought to claim the freedom promised them in the proclamation. This included Hiram Reed and Frank Lewis. Enslaved by Thomas L. Snead, aide to the former secessionist governor of Missouri, they were the first to be emancipated.6

Lincoln responded sharply to Frémont’s edict, outlining how some points in it gave him “some anxiety”:

I think there is great danger that the closing paragraph, in relation to the confiscation of property, and the liberating slaves of traiterous owners, will alarm our Southern Union friends, and turn them against us—perhaps ruin our rather fair prospect for Kentucky.

After expressing his disapproval of this measure, Lincoln continued, “Allow me therefore to ask, that you will as of your own motion, modify that paragraph.”7

In a September 8 reply, Frémont justified his action by likening his issuing of the proclamation to a tactical decision: “It was as much a movement in the war as a battle is.” He refused to modify the order and continued to insist that he “acted with full deliberation and upon the certain conviction that it was a measure right and necessary, and I think so still.”8

Frémont’s wife, Jessie Benton Frémont, who was a daughter of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton and later famous for her writing, hand-delivered the letter, carrying it from Missouri to Washington, D.C. She presented it to the president at the White House late in the evening of September 10. Some scholars have argued that her attempt to persuade Lincoln only made him more resistant. He dismissed her as a female politician and rejected Frémont’s proclamation, eventually removing him from his post as major general. The President responded by reiterating his objection to the confiscation of property and liberation of slaves within Frémont’s edict, he said it did not align with the August 6 act that Congress had passed in response to Butler’s actions at Fort Monroe, since that had only allowed for the freeing of slaves who were employed in service hostile to the government.9

Perhaps it had been Jessie Frémont’s own ardent antislavery convictions that pushed her to defend her husband’s proclamation. Or as some have argued, her role in helping him to draft the original proclamation.10 Ultimately Frémont’s edict and effort toward emancipation were unsuccessful.

When she learned that Lincoln had countermanded General Frémont’s order for emancipation, Eddy expressed her disappointment through poetry. In December 1861, she penned a poem in praise of Frémont’s efforts. It reflected on his actions and their consequences, painting them as heroic, despite their immediate failure:

Sonnet

To

Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont

By Mary M. Patterson

Ah! thou the fearless and the free

What lofty aims now guideth thee?

What other beams O! Patriot, shine

In that commanding glance of thine?

No shade of doubt or weak despair

Blend with indignant sorrow there.

Justice & Truth must wave on high

The Country owns thy “battle cry”-

Her “Mount of freedom x”- to devine [sic],

And makes thine inmost heart her shrine.

She waits thy yet indignant claim

To juster fate and stainless fame,

The “scourge” and “chain” to trample down,

To crown her hopes and wear her crown

Rumney Dec. 13. 1861.

x Fremont signified Mount of Freedom11

Making a play on the spelling of his name, Eddy likened Frémont to a “Mount of Freedom,” praised him as a “Patriot,” “fearless,” and guided by “lofty aims.” She showed her staunch support of the disgraced Major General, once again demonstrating her firm stance against slavery and continued interest in the cause of emancipation.

Eddy was not the only writer to admire Frémont’s actions through verse. John Greenleaf Whittier also praised the general: “THY error, Frémont, simply was to act A brave man’s part, without the statesman’s tact.” He compared Frémont’s actions to those of the French literary hero Roland and exhorted, “Still take thou courage! God has spoken through thee, Irrevocable, the mighty words, Be free!”12

While Eddy and Whittier both praised the dishonored general’s efforts, Frémont’s seeming failures may have ultimately proved influential. Abraham Lincoln eventually passed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, granting freedom to enslaved persons within the Confederate states.

For more on this topic, read the “From the Papers” article “Mary Baker Eddy’s convictions on slavery.”

- Peter Haggerty to Mary Baker Eddy, 20 August 1861, 653.68.026; Mary Baker Eddy, Footprints Fadeless, n.d., A10402, 7–9

- Mary Baker Eddy, “Biography”, n.d., A10219, 2; S. J. Hanna, “Malicious Falsehoods, The Christian Science Journal, December 1898, https://journal.christianscience.com/issues/1898/12/16-9/malicious-falsehoods?s=copylink

- John C. Frémont, “John C. Frémont to Abraham Lincoln, July 30, 1861,” The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, 1880–1901), 1st series, 3:415.

- John C. Frémont, “Proclamation,” 30 August 1861,” The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, 1880–1901), 1st series, 3:466–468

- John C. Frémont, “Proclamation,” 30 August 1861,” The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, 1880–1901), 1st series, 3:466–468

- Jessie Benton Frémont and Francis Preston Frémont, Great Events in the Life of Major General John C. Fremont, F.R.G.S. Chevalier de l’Ordre pour le Merite; etc. and Jessie Benton Frémont, Unpublished, Bancroft Library collection 1891, 267.

- Abraham Lincoln, “Abraham Lincoln to John C. Frémont, September 2, 1861”, in The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume 4 (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1953).

- John C. Fremont, “John C. Fremont to Abraham Lincoln, Sunday, September 08, 1861 (Proclamation and situation in Missouri),” Abraham Lincoln and Previous Proclamations, accessed January 7, 2022, https://kpgmuh390.omeka.net/items/show/11

- Abraham Lincoln, “Abraham Lincoln to John C. Fremont, Wednesday. 1861” in Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 to 1916: https://www.loc.gov/item/mal1159000/

- Vernon L. Volpe, “The Frémonts and Emancipation in Missouri,” The Historian, Vol. 56, No. 2 (1994): 342–345.

- Mary Baker Eddy, “Sonnet To Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont”, 13 December 1861, A10008, https://mbepapers.org/?load=A10008

- John Greenleaf Whitter, “Anti-Slavery Poems In War Time To John C. Frémont,” The Poetical Works in Four Volumes (Boston, New York: Houghton Mifflin and Co.), 1892; Bartleby.com, 2013: https://www.bartleby.com/372/301.html, accessed January 7, 2022.