From the Papers: The Chautauqua Movement and Christian Science

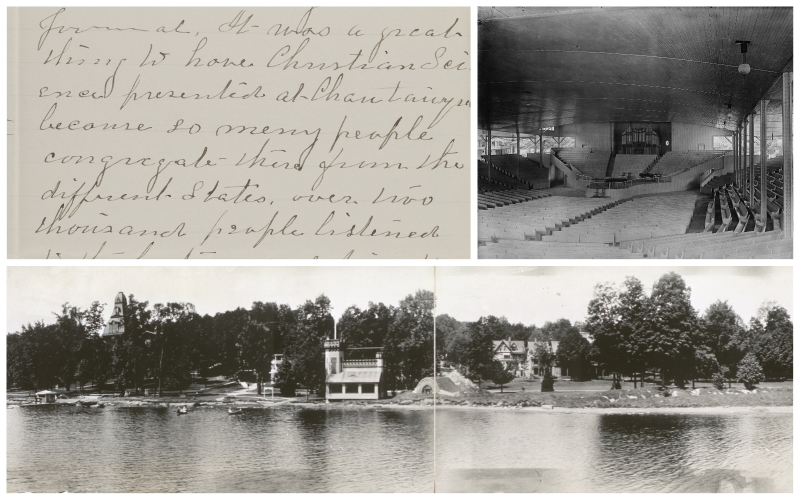

Sarah J. Clark to Mary Baker Eddy, August 22, 1886, 050.15.007. Assembly hall at Chautauqua, courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-det-4a03988. Chautauqua waterfront, courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

During the summer of 1873 John Heyl Vincent, a Methodist preacher, and Lewis Miller, an inventor-manufacturer, founded an institute for Sunday school teachers on the shores of Lake Chautauqua in western New York. It would grow into an educational movement, which eventually welcomed Mary Baker Eddy’s followers and served as a platform for publicizing Christian Science teachings. Chautauqua’s unique blend of leisure and study fostered an interdenominational community where Eddy’s new religion spread and flourished.

On the heels of the Second Great Awakening,1 cofounder and former circuit-riding Methodist minister John Vincent sought to counteract evangelical emotionalism with learning. He believed education marked a maturation of the late nineteenth century revivals. At the center of Chautauqua lay the conviction that “life is one, and that religion belongs everywhere.”2 The institute offered both spiritual and secular instruction, because “all things secular are under God’s governance” and “are full of divine meanings.”3 What became known as the Chautauqua Institution occurred annually during the summer vacation season, as an intensive eight-week course that fused education and recreation in the idyllic rural setting of western New York.

Chautauqua found quick success. It appealed to social groups previously excluded from higher learning—particularly white, middle-class women with less access to formal college. By the late 1880s it had become a forerunner of adult education and a center for discussion and debate, with Social Gospel-minded academics, politicians, preachers, and reformers invited to speak within its classrooms. The institute also offered a correspondence course through the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle (CLSC).4 Chautauqua’s success coincided with, and resulted from, a burgeoning industrial economy that brought with it increased prosperity, leisure time, and affordable transportation for many. The institute hoped to strengthen democratic society, providing the “tools for a growing populace to better exercise their rights.”5 Along with the CLSC, the institute managed a Chautauqua book-a-month club, while also encouraging the founding of nearly 10,000 independent chapters, known as “Chautauqua circles,” throughout the country by the 1890s.6

Chautauqua’s resultant democratization of adult education aligned well with the Christian Science emphasis on learning and spiritual and educational growth. As a result, many of Eddy’s students were drawn to the institute, and Christian Scientists who spoke at and attended the institute encouraged others to join the fold. This was particularly true for women, who found in both Chautauqua and Christian Science the opportunities for speaking, teaching, and learning unavailable to them in larger nineteenth-century American culture.

As cofounder, Vincent had initially discouraged Christian Scientists from speaking at Chautauqua and “utterly refused to have any faith healing7 on the grounds.”8 But by 1886 Christian Scientists were lecturing during the summer courses. In 1886 Sarah Jane Clark, who taught Christian Science in nearby Jamestown, New York, wrote to Eddy’s secretary Calvin Frye, requesting that he forward her the mailing address of Christian Scientist Orrin P. Gifford. She had heard that he was to lecture about Christian Science at Chautauqua. Clark followed up this initial request with another letter to Eddy, including the paper that Gifford had delivered at the institute. “He presented the subject [Christian Science] in a clear concise manner,” she wrote, “taking up the points every one is eager (who is interested) to have explained condemnation, divinity of Christ prayer and Atonement his illustration were good and will not soon be- forgotten.”9 Clark continued by describing how Gifford’s talk was publicized in the local community: “The lecture was announced in the Jamestown Journal and quite a party went from here and they and many more are anxiously waiting for it to be published.”10 And she concluded:

It was a great thing to have Christian Science presented at Chautauqua because so many people congregate there from different States, over two thousand people listened to the lecture and five to the sermon and they expressed themselves very much pleased with the sermon many said it was the best thing they had heard at Chautauqua this season – to me it was the essence of C. Science- Christian Science and Faith Healing have clasped hands at Chautauqua.11

Clark continued healing and teaching in the Chautauqua region. This reinforced the discussion of Christian Science at the institute and strengthened its growing community of followers in western New York.

While it is not clear how many attendees of the Chautauqua Institute became interested in Christian Science, a number of its former students reached out to Eddy, expressing interest in Christian Science. In July 1887 Charles and Susan Bowles wrote, in hopes of joining her class in Boston after attending Chautauqua that August.12 Delia Hanson wrote Eddy in August 1888:

I went to Chautauqua Lake the following week on the invitation of a Rev (who had studied with Mrs Mc Coy in N Y last summer) to treat his wife. He offered his efforts and influence in case I was successful to get me a class.13

Hanson wrote again that October, saying she had “met a lady at Chautauqua from New Orleans who said they had Metaphysics there but did not know of ‘Science and Health,’ or Mrs Eddy.”14

Mrs J. S. McManns, a graduate of the four-year correspondence course offered by the Chautauqua Institute, expressed her interest in Christian Science treatment and healing, after discovering a lump in her breast.15 John S. Norvell, a Baptist minister at First Baptist Church in Emerson, Iowa, and a student of Eddy, attended the Chautauqua Assembly for two weeks in the summer of 1887.16 J. R. Mosley, who studied under Alice Jennings and served as the Second Reader of the Christian Science church in Macon, Georgia, also delivered Christian Science lectures at Chautauqua Assemblies.17

Once Chautauqua Assemblies were set up throughout the US, Christian Scientists invited Eddy to speak at their local chapters. Robert Clark was one of them. He wrote Frye enclosing an invitation to the Texas-Colorado Chautauqua meeting, asking Eddy to “be present in person and deliver an address to the people of this section of the country, on this occasion.”18

Others told Eddy how they had witnessed healings at Chautauqua. For example Mrs. W. J. Bell wrote, explaining how her daughter Freeda was healed at a North Dakota Chautauqua convention in 1884, after falling out of a hammock and fracturing her arm; a Christian Scientist healed her, and the next day she went to kindergarten and was able to use the arm within three days.19

The religious and educational principles at Chautauqua’s core aligned well with Christian Science. The learning retreat’s developing liberalism and regard for alternative views, within its broad moral boundaries, nurtured an ecumenical community that welcomed Catholics, Jews, and Protestants to pursue learning on its grounds. Current research at the Mary Baker Eddy Papers is beginning to reveal how Christian Scientists found acceptance in the Chautauqua community, while also using its established networks to lecture on Christian Science and promote an awareness of it in late nineteenth-century America.

- The Second Great Awakening was a series of Protestant religious revivals that swept the United States from 1795 to 1835. Religious gatherings held on the frontier took the form of camp meetings, held in the open air under the shelter of tents. These evangelical revivals found particular success in the Methodist and Baptist denominations, and encouraged many to put their faith into action through participating in reform movements such as temperance and women’s suffrage. Charles Grandison Finney is known for the revival meetings he led in western New York, while other more conservative theologians, including Timothy Dwight and Lyman Beecher, led the revival movement within the Congregational Church.

- Andrew C. Rieser, The Chautauqua Moment in U. S. History, Alexandria, VA: Alexander Street Press, 2007.; John Heyl Vincent, The Chautauqua Movement (Boston: The Chautauqua Press, 1886), 4, 31, 20; John Heyl Vincent, A History of the Wesleyan Grove, Martha’s Vineyard, Camp Meeting (Boston: Geo. C. Rand & Avery, 1858), 10, 11.

- Rieser, The Chautauqua Moment in U. S. History, 1-12.; Vincent, The Chautauqua Movement, 4, 31, 20; Vincent, A History of the Wesleyan Grove, Martha’s Vineyard, Camp Meeting, 10, 11.

- John C. Scott, “The Chautauqua Movement: Revolution in Popular Education,” The Journal of Higher Education, vol. 70, issue 4, (1999), 390–395; Rieser, The Chautauqua Moment in U. S. History, 1–12.

- Rieser, The Chautauqua Moment in U. S. History, 1–12.

- Rieser, The Chautauqua Moment in U. S. History, 1–12.

- Faith healing or faith cure was based on the idea that faith in divine healing was a gift of the Holy Spirit and that illness was not sent by God, but that instead God promised freedom from illness to Christian believers. https://mbepapers.org/?load=G00009

- Sarah J. Clark to Mary Baker Eddy, August 22, 1886, https://mbepapers.org/?load=050.15.007

- Sarah J. Clark to Calvin A. Frye, 17 June 1886, https://mbepapers.org/?load=949.93.013; Sarah J. Clark to Mary Baker Eddy, 2 August 1886, https://mbepapers.org/?load=050.15.006

- Sarah J. Clark to Calvin A. Frye, 17 June 1886, https://mbepapers.org/?load=949.93.013

- Sarah J. Clark to Calvin A. Frye, 17 June 1886, https://mbepapers.org/?load=050.15.007

- Charles and Susan Bowles to Mary Baker Eddy, 30 July 1887, https://mbepapers.org/?load=482.55.004

- Delia C. Hanson to Mary Baker Eddy, 2 August 1888, https://mbepapers.org/?load=135.23.007

- Delia C. Hanson to Calvin A. Frye, 10 October 1888, https://mbepapers.org/?load=981.97.017

- Mrs. J. S. McManns to Mary Baker Eddy, 19 July 1886, https://mbepapers.org/?load=948.93.012

- Sarah E. Benford to Mary Baker Eddy, 2 July 1887, https://mbepapers.org/?load=522.57.012

- J. R. Mosley to Mary Baker Eddy, 14 February 1901, https://mbepapers.org/?load=170.29.001

- Robert M. Clark to Calvin A. Frye, 24 March 1889, https://mbepapers.org/?load=612AP1.62.064

- Mrs. W. J. Bell to Mary Baker Eddy, 21 July 1901, https://mbepapers.org/?load=646B.67.031