From the Collections: Christian Science at the World’s Parliament of Religions

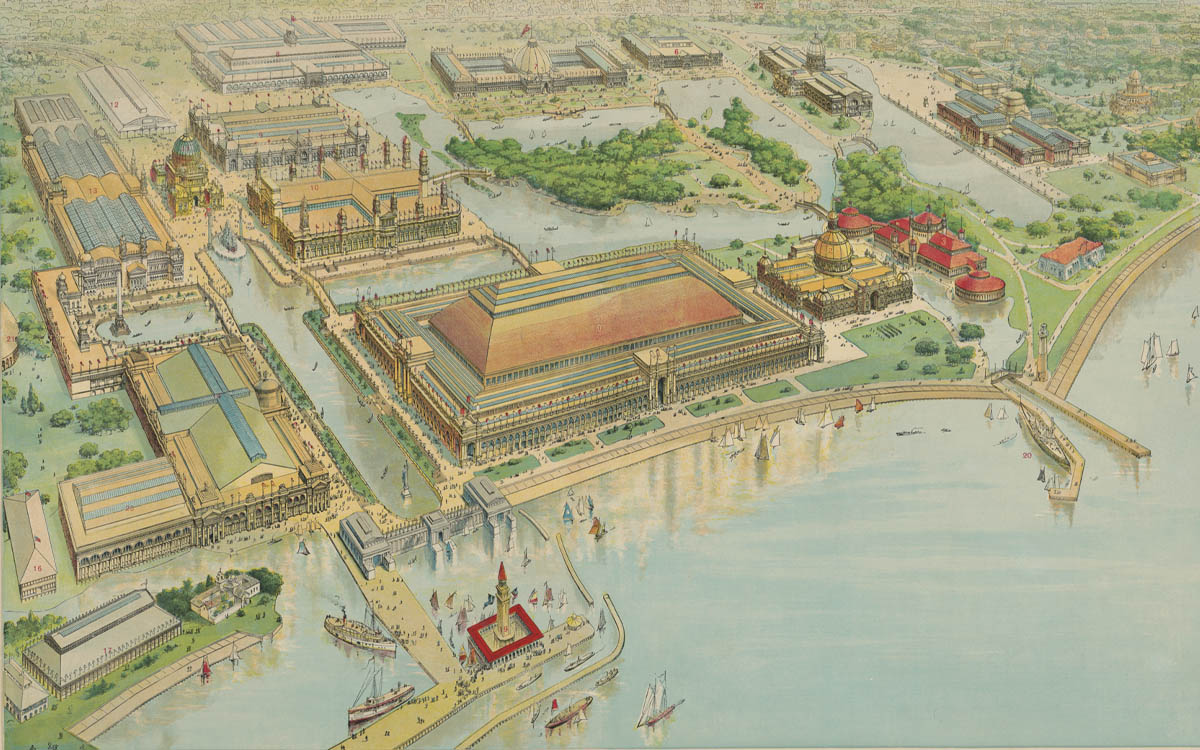

Panoramic view of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, 1893. Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-44787.

In conjunction with the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, a groundbreaking interfaith conference took place in Chicago. The World’s Parliament of Religions opened on September 11, 1893, in an auxiliary hall that today houses the Art Institute of Chicago.1 For the first time in history, representatives of many faiths around the globe gathered, under the auspices of unity and brotherhood, to discuss religion.

The Parliament came to fruition through the collaborative efforts of Charles C. Bonney, an Illinois Supreme Court judge, and John Henry Barrows, a Presbyterian pastor from Chicago.2 While Barrows is rightfully credited with being its architect, it was the brainchild of Bonney. In a letter sent to religious leaders worldwide, the message of unity and acceptance for all religions was front and center:3

We affectionately invite the representatives of all faiths to aid us in presenting to the world, at the Exposition of 1893, the religious harmonies and unities of humanity, and also in showing forth the moral and spiritual agencies which are at the root of human progress.4

Although the message of unity among all religions was elevated as the ultimate goal, there was also criticism that the “Parliament itself was Christian-centric with a strong undercurrent of evangelization directed at the other religious leaders.” According to scholar Katherine Marshall, the event “brought together leading voices in the emerging religious studies field with theologians and religious leaders.”5

Initially, some speculated that Christian Science would not be recognized as a denomination, thus excluding the religion entirely from the conversation on the world stage. Mary Baker Eddy was hesitant and skeptical concerning a presentation and display of her teachings in the exposition. The benefits of inclusion were evident, as well as the negative optics of the Church of Christ, Scientist, potentially being denied a space at the event.

Responding to requests for her presence in Chicago, Eddy was emphatic:

In reply to all the invitations from Chicago to share the hospitality of their beautiful homes at any time during the great wonder of the world ― the World’s Fair ― I say: Do not expect me, I have no desire to see or to hear what is offered upon this approaching occasion.

I have a world of Wisdom and Love to contemplate that concerns me and you infinitely beyond all earthly expositions or exhibitions. In return for your kindness, I earnestly invite you to its contemplation with me, and preparation to behold it.6

The inclusion of Christian Science as a denomination at such a large level would provide Eddy’s new religion both exposure and acceptance. And the invitation for Christian Scientists to present an address allowed for the tenets of their faith to be shared on the world stage. This watershed moment would happen just one year after the reorganization of her fledgling church as The Mother Church, The First Church of Christ, Scientist.

Eddy’s students were the leading force in her ultimate agreement for Christian Science to play any role in the conference. And through their continued perseverance, the church was indeed allotted a place at the event.

Once it became clear that there would be space and a platform provided, preparations began in earnest. While Eddy was reluctant to directly take part in the event, she nevertheless carefully guided the messaging to showcase the religion in the best possible light.

In a letter to her student William B. Johnson, Clerk of The Mother Church and a member of its Board of Directors, Eddy carefully designated the way she preferred the address to be prepared:

I desire you to select the very best, comprehensive quotations to be found in all my works …. Be careful to quote no passages that assail the religious beliefs of any sect….

My reasons for this are that “What is written, is written”. The texts are contained in these works, and I for one would not venture to depart from the fundamental teachings of these books with all the labor bestowed on them. I think that nothing can be said that would be more satisfactory, on the subject, that I have given out, to define in the manner aforesaid Christian Science.7

A series of back-and-forth documents shows the progression of edits to the address. Eddy—along with Calvin Frye, her secretary, and Septimus J. Hanna, who was currently serving as pastor of The Mother Church8 and editor of The Christian Science Journal—carefully constructed the message that would be read at the Parliament on September 22.9

As the theme of the conference centered on unity and brotherhood, the tone and title of the address—“Unity and Christian Science”—reflected the inclusive nature of the event.10

The following excerpt integrates the conference theme with the basic tenets of Christian Science:

The universal brotherhood of man is a principal factor in Christian Science. Having one God is having one Father; and this Scientifically establishes the brotherhood of man. The first commandment of the Hebrew decalogue, understood, unfolds the true Principle of the brotherhood of man, and the impossibility for God’s children to have antagonistic minds and so war one with another. United in their Divine Principle they practice divinity, and so fulfill the scripture, “Be ye perfect even as your Father which is in Heaven is perfect.”11

Additionally, by creating the connections between the Scriptures and Christian Science—as is seen in the next passage, as well as the one above—Eddy provided the audience with a rich historical precedent for Christian Science:

The Hebrew term which gives another letter to the word God, and makes it Good, unites Science and Christianity; whereby we learn that Good is universal, and the Divine Principle, Life, Truth, Love. This Triune Good is reached through goodness, — through Mind instead of matter; Soul instead of sense, understanding and demonstration.12

The address received an enthusiastic response. Eddy and her students were initially exuberant. According to biographer Robert Peel, “The whole household, including Mrs. Eddy herself, was caught up in a tide of jubilation as reports came in of the excellent impression made by the Christian Science presentation in general and her paper in particular.”13

But, unfortunately, events did not go off without a hitch. Hanna submitted the address for publication expressly against Eddy’s orders. And although it was a compilation of excerpts from Eddy’s published writings, the speech was printed as Hanna’s own work.14 While immediate steps were taken to rectify the mistake, Hanna’s misstep further solidified Eddy’s resolve to keep the address out of publication.

There were also requests to have the Christian Science address included in The History of The World’s Parliament of Religions by John Henry Barrows.15

Eddy explained her opposition to this in a letter to Bonney:

My address read by Judge Hanna before the Parliament of Religions was copyrighted. This renders the newspapers publishers of it legally responsible….

A word further. I was in the first instance opposed to having my students in Christian Science (which number many thousands) take part in the World’s Fair. Christian Science inculcates spiritual love for all men but no worldliness. I fear the ambition of my students was touched. As it is I decline to have my aforesaid Address published in the World’s Fair book which is to contain these matters.

My God demands of me to come out from the world and touch not the objects which can in any way deviate my spiritual sense from peace and good will.16

Eventually, through continued correspondence and cajoling on the part of her Chicago student Edward A. Kimball, Eddy agreed that an abridged version of the address could be included in the publication of Barrows’s compilation.17 The first and second volumes of this work are included in The Mary Baker Eddy Library’s Chestnut Hill Books collection.

Peel contends that “far from making for greater unity between Christian Science and the traditional Christian churches, the Parliament of Religions crystallized opposition against Mrs. Eddy and the Church of Christ, Scientist.” He points to Eddy’s longstanding apprehensions about participation as stemming from a perception more finely tuned than even capable adherents such as Hanna and Kimball could fully grasp at the time—that the net effect of the Church’s participation at the Parliament could be negative:

More than eighty years later many of the hints in Mrs. Eddy’s letters come clear. When social historians refer back to the Parliament of Religions, they almost unanimously see its chief or sole significance in its popular introduction of Oriental religion to America. If Christian Science is mentioned at all—and this is rare indeed—it is in the context of the impression made by such non-Christian exotica as the Vedanta, Baha’i, and those arcane forms of Oriental thought hitherto represented to Americans by Theosophy.18

It would be another hundred years before, at the event’s 1993 centennial, the modern interfaith movement would spring from seeds sown in Chicago.19 But Christian Scientists immediately learned some stiff—and useful—lessons on what it could mean for their growing religion to be introduced on a world stage.

This article is also available on our French, German, Portuguese, and Spanish websites.

- “1893 World’s Parliament of Religions,” Art Institute of Chicago website, https://www.artic.edu/1893-worlds-parliament-of-religions.

- Marcus Braybrooke, “Charles Bonney and the Idea for a World Parliament of Religions,” The Interfaith Observer, 15 June 2012, http://www.theinterfaithobserver.org/journal-articles/2012/6/15/charles-bonney-and-the-idea-for-a-world-parliament-of-religi.html

- Marcus Braybrooke, “John Henry Barrows: Producing the First Parliament of Religions,” The Interfaith Observer, 15 July 2012,

http://www.theinterfaithobserver.org/journal-articles/2012/7/15/john-henry-barrows-producing-the-first-parliament-of-religio.html - Marcus Braybrooke, “John Henry Barrows: Producing the First Parliament of Religions,” The Interfaith Observer, 15 July 2012,

http://www.theinterfaithobserver.org/journal-articles/2012/7/15/john-henry-barrows-producing-the-first-parliament-of-religio.html - Katherine Marshall, “The Parliament of the World’s Religions: 1893 and 1993,” The Interfaith Observer, 15 September 2015, http://www.theinterfaithobserver.org/journal-articles/2015/9/3/the-parliament-of-the-worlds-religions-1893-and-1993.html?rq=Marshall

- Mary Baker Eddy, “Card,” The Christian Science Journal, April 1893, 20.

- Eddy to William B. Johnson, 31 July 1893, L03295.

- The following year, on December 19, 1894, Eddy would ordain the Bible and Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures as Pastor of The Mother Church.

- “Christian Science at the World’s Religious Congress,” Journal, November 1893, 343.

- Septimus J. Hanna to Eddy, 2 September 1893, IC 033a.13.027.

- Eddy, “Unity and Christian Science,” A10451C. While this citation is not a direct quotation from Eddy’s published writings, it echoes statements now found on pages 276 and 340 of Science and Health.

- Eddy, “Unity and Christian Science,” A10451C. This is similar to a passage found in Eddy’s The People’s Idea of God, 2.

- Robert Peel, Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Authority (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1977), 52.

- Peel, Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Authority, 52–59.

- John Henry Barrows D.D., The History of the World’s Parliament of Religions, 2 vols. (Chicago: Parliament Publishing Company, 1893).

- Eddy to Charles C. Bonney, 27 September 1893, L09475.

- Peel, Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Authority, 57.

- Peel, Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Authority, 58, 57.

- See Parliament of the World’s Religions, “Parliament Convenings,” 2015–2022, https://parliamentofreligions.org/.