From The Papers: “Maj Anderson and Our Country”

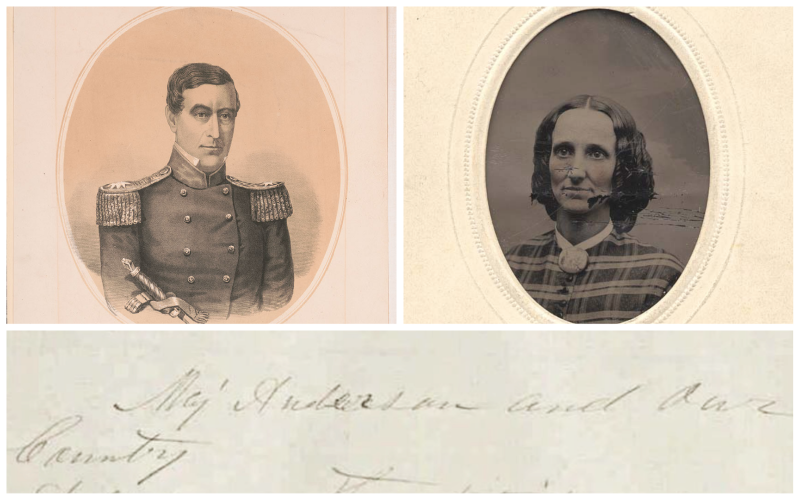

Lithograph: “Major Robt. Anderson, the heros of Fort Sumter,” circa 1861, courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-pga-12446. Tintype studio portrait: Mary Baker Eddy, circa 1863, unidentified photographer, P00161. Manuscript: “Maj Anderson and Our Country,” 6 February 1861, A10007.

Listen to this article

Early in 1861, underlying tensions between the American North and South were fast approaching a boiling point. From Rumney, New Hampshire, Mary Baker Eddy carefully monitored the events leading to a civil war that was soon to grip the country.

On February 6, 1861, Eddy authored a poem, “Maj Anderson and Our Country.” Transcribed and annotated on the Mary Baker Eddy Papers website, it offers important insights into some of her compelling views and convictions not long before her discovery of Christian Science. Praising Major Robert Anderson (1805–1871), commander of the Federal forces in Charleston, South Carolina, the 13-stanza work begins:

Brave Anderson, thou patriot– soul sublime

Thou morning Star of errors’ darkest time!

Prince of the lion–hearted Jackson mould,

Thy valor mocks the rebel at his hold

O! weak Buchanan, join thy country’s cause

And aid her champions to defend her laws;

Our Eagles’ eye-beams dart unwonted fires —

His kindling glance the warrior’s heart inspires

Is honor’s lofty soul forever fled?

Is virtue lost? is martial ardor dead?

A cankering where vested power should dwell!

No second Washington — no dauntless Tell?

Save with Fort Sumter’s hero and the band

Who round their banner, firm, exultant stand;

Illustrious names! still, still, united beam

The hero’s halo and the poet’s theme

Is this the spot to write our Bunker Hill,

Freedom’s next battleground for fame to fill?

Or but the feint which Southern traitors play

Eddy’s verse was in response to Anderson’s bold decision to move Union troops from Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island, South Carolina, to the nearby unfinished Fort Sumter. South Carolinians would perceive Anderson’s movements as a threat and eventually make preparations to retake Sumter. Knowing the gravity of Anderson’s decision, and the likelihood that his actions would provoke war, Eddy was boldly backing his move and expressing her support of his efforts to protect the Union, even at the risk of war.

Anderson took over command of Charleston’s Union forces in November 1860 when President James Buchanan, nearing the end of his term in office, was trying to avoid the outbreak of sectional conflict. A diplomat at his core, Buchanan had adopted a strategy that favored avoiding violence. His hesitancy to act was further influenced by his divided cabinet, which included Secretary of War John B. Floyd, a Virginia-born southern sympathizer. On arrival in South Carolina, Anderson submitted a report to Floyd, recommending that Fort Sumter be garrisoned and two companies be sent to occupy it, as well as Castle Pinckney, a small fortification in Charleston Harbor. Anderson feared that if Sumter fell into Confederate hands, both Fort Moultrie and Castle Pinckney would lose access to reinforcements and supplies. He also recommended that any action be taken quietly, so as not to alert South Carolinians and allow them to outmaneuver Anderson’s designs.2

Anderson’s superiors denied his request for reinforcements and instructed him to defend Fort Moultrie using the resources on hand, without provoking the locals.3 Finding this approach unrealistic and his position indefensible, Anderson took matters into his own hands and covertly moved the Union soldiers under cover of darkness. On the day after Christmas, both the local South Carolinians and Anderson’s superiors were surprised to find that Anderson had transported his troops to occupy Fort Sumter.

The reports of Anderson’s actions in newspapers throughout the United States incited much public debate. While Southern publications viewed Anderson’s behavior as unacceptable and in violation of the president’s orders, Northern papers sided with Anderson in his decisive action against the South, some going as far as labeling Buchanan’s behavior as disloyal and worthy of impeachment.4 Eddy had joined the conversation in support of the Union commander. Eight days after she wrote it, her poem was published in Concord, New Hampshire’s Independent Democrat, as seven Southern states gathered in Montgomery, Alabama, over 1,000 miles away, to form the Confederacy.5

Eddy’s sentiments are plainly evident in her poem. Her words stood firmly with the Union—and against Buchanan and his secretary of war, for she did not shy away from directly criticizing the president:

O! weak Buchanan, join thy country’s cause

And aid her champions to defend her laws;

Not only did she suggest that Buchanan had moved against the cause of the country he led; she went so far as to intimate that his actions bordered on treason:

Is honor’s lofty soul forever fled?

Is virtue lost? is martial ardor dead?

A cankering where vested power should dwell!

No second Washington — no dauntless Tell?

While Eddy boldly expressed her disappointment in Buchanan’s leadership, she praised Anderson for exhibiting the valor she felt the president lacked, likely referring here to former president and army general Andrew Jackson, whom she admired:

Prince of the lion-hearted jackson mould[sic],

Thy valor mocks the rebel at his hold.

Yet Anderson’s actions on behalf of the Union were far from expected. His move had likely been a surprise to both Buchanan and Floyd, since his Southern roots and marital connections predicted otherwise. Born on the outskirts of Louisville, Kentucky, he had married the daughter of General Duncan Clinch, a Georgia slaveholder who had bequeathed some of his slaves to Anderson through his daughter. He attended West Point before fighting in the 1832 Black Hawk War and the Second Seminole War, as well as the Mexican War, where he was wounded and commended for valor. When he placed Anderson in command at Charleston, Floyd likely expected him to demonstrate some sympathy with the Southern cause, even though Anderson’s family took a strong Unionist stand and his fervent religious faith led him toward a pacifist inclination. Nevertheless, Anderson moved decisively counter to Southern sentiments, much to the chagrin of Buchanan and Floyd.6

In Eddy’s view, Anderson assumed the leadership role that Buchanan had abdicated, spurning pacifist tendencies and taking a stand that would likely provoke war:

Save with Fort Sumter’s hero and the band

Who round their banner, firm, exultant stand;

illustrious names! still, still, united beam,

The hero’s halo and the poet’s theme

Eddy’s support was far from casual; she understood the gravity of war. And she appreciated the eventual bloodshed that could affect her home and family. But she was obviously willing to sacrifice her family’s safety and comfort for a higher moral cause:

Yet would I yield a husband, child, to fight

Or die the unyielding guardians of right.

Than that the lifeblood circling through their veins,

Should warm a heart to forge new human chains.

I then would mourn them proudly, and my grief.

In woman’s sacrifice might seek relief,

a noble sorrow, cherished to the last–

When every meaner woe had long been past

Eddy eventually lived the sacrifices she predicted in her poetry. Her second husband, Daniel Patterson, was taken prisoner by the Confederate Army, and her son fought for the Union Army.7

Eddy’s publication of this poem, coupled with subsequent letters and poems she wrote expressing her views on slavery and the Civil War, placed her in a minority.8 While most Northern women supported the war as an effort to uphold and preserve the Union, few believed that it should result in either abolition or emancipation. While her poem about Anderson did not explicitly state her views on slavery—which she would make clear through her publications later that year—it did firmly express her support of the Union.

Later in 1861, Eddy wrote letters and poems explicitly against the institution of slavery, joining what historian Thavolia Glymph has identified as an important minority among Northern women who “felt their souls assaulted by slavery and suffered ‘persecution’ for their views.” Through sewing circles, fundraising efforts, the sheltering of fugitive slaves, and published works, these women stood at the forefront of the abolition movement. According to Glymph, “They answered the long-gnawing assault on their souls with the weapons most readily available to them: giving lectures, placing anonymous posts in newspapers, organizing freedmen’s relief societies, and going to the front as nurses, missionaries, and teachers.”9 Although they remained a minority, their works and opinions counted.

Even before shots were fired at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, signaling the start of the Civil War, Eddy’s poem had predicted the significance of those events taking place in Charleston:

Is this the spot to write our Bunker Hill,

Freedom’s next battleground for fame to fill?

Just as Bunker Hill had been a decisive battle at the outset of the Revolutionary War some 86 years earlier, the Battle of Fort Sumter would prove a similarly pivotal event. For Eddy, this poem also signified a beginning. It was the start of her public efforts—through letters, poems, and other publications—to support the Union and stand against the evils of slavery.

- ”Maj Anderson and Our Country,” 6 February 1861, A10007.

- “Major Robert Anderson to Colonel Samuel Cooper, December 1, 1860,” The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, 1880–1901), 1st series, 1:81.

- “Colonel Samuel Cooper to Major Robert Anderson, December 1, 1860,” The War of the Rebellion, 1st series, 1:82.

- “The Progress of Events,” Abbeville Press, 4 January 1861; “Important from Charleston,” Delaware Gazette, 28 December 1860; “The President Wavering,” New York Daily Tribune, 29 December 1860.

- “Major Anderson and Our Country,” by “Mary M. Patterson,” The Independent Democrat, 14 February 1861.

- Wesley Moody, The Battle of Fort Sumter (New York: Routledge, 2016), 45.

- Daniel Patterson was taken prisoner by the Confederate Army in March 1862. He wrote to Mary Baker Eddy from prison in Richmond, Virginia. Daniel Patterson to Mary Baker Eddy, 2 April 1862, L16248, L16253

- Eddy wrote a number of letters and poems in support of emancipation and the Union cause during the Civil War. These include V03472, L02683, 653.68.026, and A10008. These letters and poems have been addressed in previous articles in the “From the Papers” series, including “Mary Baker Eddy’s support for emancipation” and “Mary Baker Eddy’s convictions on slavery.”

- Thavolia Glymph, The Women’s Fight (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020), 131.