The work of Jean McDonald: an appreciation

By Amy B. Voorhees

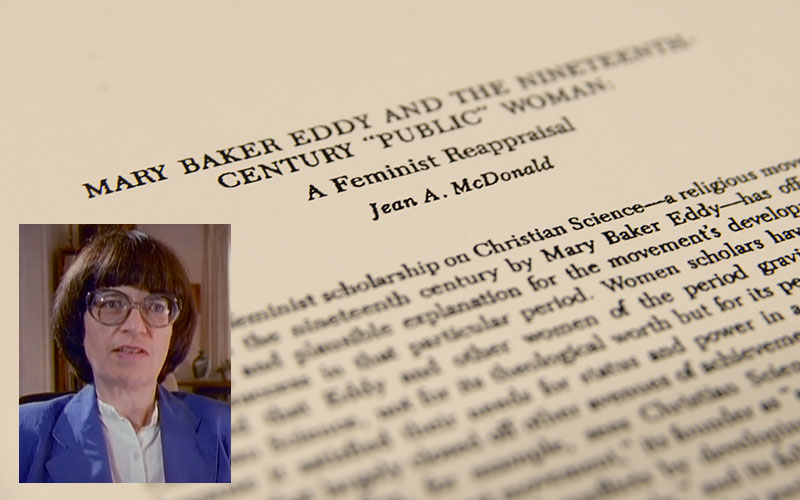

Jean McDonald, c. 1988. “Mary Baker Eddy and the Nineteenth-Century ‘Public’ Woman: A Feminist Reappraisal,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, Spring 1986, 89.

Sometime in the mid-1970s, Jean Angela McDonald jotted down notes on the back of an advertisement for a Christian Science lecture in her adopted hometown of Minneapolis—William Henry Alton, C.S.B., would be speaking on the topic “What’s your greatest need?” In her small, rounded handwriting, she wrote comments about testimonial letters of healing that had been published in The Christian Science Journal.

A decade later, Dr. McDonald featured those letters prominently in her 1986 article “Mary Baker Eddy and the Nineteenth-Century ‘Public’ Woman: A Feminist Reappraisal.”1 The article introduced evidence that recalibrated descriptions of Christian Science and its Founder within the community of scholars studying women and religion, and beyond. The ready reception it found testifies to a capacity for self-reflection and flexibility within that community, as well as to the article’s fundamental value.

An innovative work

“By mining letters in The Christian Science Journal,” asserts scholar Jeanne Halgren Kilde, Dr. McDonald “offered a powerful antidote to…the misapprehensions of scholars” in her own time about why people became Christian Scientists, as well as to “the stereotypes” about Mary Baker Eddy when she emerged as a public figure in the nineteenth century.2 In their testimonials, the article shows, women overwhelmingly represented themselves as becoming Christian Scientists because it “satisfied their sense of reason and truth.”3 This was a groundbreaking assertion at the time. Prior works tended to assume early Christian Scientist women joined the religion primarily for societal advancement or simply to achieve health. Though these factors at times attracted them, Dr. McDonald found, they identified things of the Spirit as having the real depth and pull to retain them.

A project like Dr. McDonald’s “wasn’t very academically fashionable in the 1980s,” writes the historian Mary Farrell Bednarowski. But she can relate to its innovative methodology and conclusions. Early in her own work, she says, “it occurred to me that if you want to know why people are drawn to a particular religious tradition or theological idea, new or old, you could actually ask them—either in person or indirectly by reading letters, memoirs, interviews, testimonials.” She appreciates how Dr. McDonald did this. Regarding Mary Baker Eddy, Dr. Bednarowski notes, “I continue to think of her as a woman who took on the endlessly frustrating issue of theodicy and concluded that there was no way out of that theological/psychological/spiritual box without a radical change in traditional models of God.”4

Dr. McDonald’s article chronicles with unsentimental precision the sexist rhetoric Mrs. Eddy contended with, contextualizing the forms it took within her historical era. This component of the Christian Science Leader’s biography was vaguely accepted at the time—but not much dwelt-on and often overlooked, as studies often assumed the fame of her later years, or some personality trait, exempted her from it. Instead, the article shows how it echoed in scholarly work about her long afterward.

Their “theological hunger”

Yet perhaps most enduringly, the article continually turns toward sources that establish the “theological hunger” of early Christian Scientist women. It dwells on their capacity to reason as well as to feel after divine things, as they went about their “intellectual and spiritual search.” In the process of converting from other denominations—including working out how to understand what they described as very individual experiences of Christian Science healing—and in remaining committed to this new and unusual form of Christianity, they grappled with theological and practical questions that resonated widely. Again, the piece argues what now may seem obvious but then was not: that this was their province alongside men. Dr. Bednarowski calls these passages compelling. In citing “the depth of their spiritual hunger,” she feels the author is making clear her awareness that “whatever else drew women to Christian Science, they also experienced themselves as participants in the broader theological conversations of the times.”

In the draft manuscript of a book Dr. McDonald undertook, she refers to “a ‘driving spirit,’ a ‘pressing hunger’” of a different sort, one expressed by women researchers and scholars who, despite lack of resources or a ready rewards system, could not be kept from their work.5 This could describe the author herself. Despite what must have been difficult obstacles, she remained dedicated and hungry to understand, observe, reason, and write about the history of Christian Science.

Scholarly preparation

Both of Jean McDonald’s degrees from the University of Minnesota focused on the Christian Science Founder. Her 1969 Master’s thesis, Mary Baker Eddy at the Podium: The Rhetoric of the Founder of the Christian Science Church, illustrates her novel and thorough approach to historical work.6 It includes the only known chronology of Mrs. Eddy’s public speaking events, which appear on a chart noting each event’s type (lecture, address, sermon), those based on Bible texts, and those that were impromptu.7 Chapters focus on such topics as the “chief characteristics of her public speaking” and her approach to preparation, content, technique, adaptation, and delivery. Dr. McDonald was motivated, she notes, by the small body of scholarship on the subject compared with the high volume of Mary Baker Eddy’s public talks and the cultural breadth of her name recognition. She demonstrates how the Christian Science Leader’s public speaking resonated with others of her era while also operating in newly distinctive ways, most notably through her consistent description of her religious discovery as the Comforter that Jesus promised God would send and in the unusual record of healing that attended it.

In her 1978 doctoral dissertation, printed in two large volumes, Dr. McDonald sought to understand the position early Christian Scientists saw themselves “occupying in the drama of existence.”8 In some ways, she seems to have been striving toward documenting Christian Science identity in comparative context, which became a focus of later scholarship, including my own. Her sources are again creative, unusual, and always attentive to gendered considerations. In a rhetorical exploration of “lunacy dramas” produced by self-identified opponents of Christian Scientists, she observes, “The lunatics in these dramas are invariably female, the clear-thinking heroes always men…. For science and rationality were masculine; want of science and want of rationality were feminine traits.”9 Thus male converts to Christian Science were described with emasculating rhetoric in such sources. And all Christian Scientists were described like children, as in rhetorical treatments of the working classes in Britain.

A type of prescience

Dr. McDonald was ahead of her time in selecting, handling, and analyzing sensitive historical sources. In addition to novels, she leverages cartoons, including one from Life magazine, in which Pocahontas is portrayed saving Captain John Smith through Christian Science. Close inspection shows a caricature of the Powhatan woman (anachronistically) reading the Christian Science textbook, with a derogatory slur for her and other American Indian women describing Mrs. Eddy as its author.10 Dr. McDonald’s commentary on this recalls work done three decades later by the scholar of gender and religion Pamela Klassen, who has observed that such sources sought to rhetorically discount Christian Science and its Founder by aligning her new religion with established sexist and racist caricatures.11

Within the pages of her dissertation, Dr. McDonald stuck a handful of cards with references to the latest scholarship on women and religion. She seemed to be always observing, evaluating, processing, meticulously noting sources against which to weigh her own insights. She finished her doctorate in 1978, as the volume of scholarly work on women’s history exploded. She then parlayed her many years of work into writing and publishing her article, as well as drafting chapters for a book.

Fellowship, critique, and exchange

Though a book never materialized, she found encouragement for “Mary Baker Eddy and the Nineteenth-Century ‘Public’ Woman” from Stephen Gottschalk, a historian of Christian Science and fellow adherent. He offered critical feedback and practical help for her later work, arranging an editor and typist (whom he also may have paid). True to form, his critiques were jovially blunt. He found one chapter “boring,” to which Dr. McDonald objected, “After 2 years, I still think…there’s lots of fascinating new historical detail” and even a few “laughs.” She made some edits nevertheless, then counseled him, “If you can…grit your teeth & read it through, I think you’ll agree that it may have something that needs saying after all!” Dr. Gottschalk clearly did agree regarding her overall project. “Thanks for all the good work on this,” he wrote to the editor and typist. “It’s most encouraging to Jean, and she’s been happy with the results.” He also included Dr. McDonald among other more well-known cultural figures and scholars of religion he interviewed for a film about Mrs. Eddy’s life, Mary Baker Eddy: A Heart in Protest.

Jean McDonald comes across in that film as intelligent, contained, focused, passionate, and direct, with an undercurrent of quiet thoughtfulness. Her speech is careful, diligent, with a light British lilt. It is one of the few clues we have about her personal background; her academic works contain no acknowledgements, the usual scholarly format for thanking friends, family, and colleagues. Her university did not require signature pages for the examining faculty on her academic committees, so it’s not clear which scholars she worked with in graduate school. Other than a few ship manifests pointing to someone with her rather common first and last names crossing from England on different dates in the 1950s, we have few clues about her biography. Given her unremitting focus on her work, that’s probably as she would have liked it.

A scholar-practitioner

We do know, however, that she counted herself among those drawn to the Christian Science religion because it “satisfied their sense of reason and truth.” This made her a scholar-practitioner, or a scholar who was also a practitioner of the religion she studied. This is fairly common in the field of Religious Studies, which teaches about religion rather than teaching religion itself. Scholar-practitioners have an interest in the history of their own traditions but do not teach religious tenets in their work. Those tenets, however, are meaningful to them individually as they calibrate their engagement with the field of intellectual pursuits.

Mary Baker Eddy called mere intellectualism or a “petty intellect” useless, like academic work minus “moral and spiritual culture.”12 Yet she judged “academics of the right sort” essential, including “observation, invention, study, and original thought,” and linked a “more spiritual mentality” to “the gain of intellectual momentum.”13 She wrote that Christian Science “develops individual capacity, increases the intellectual activities,” and spoke hopefully of “my students, with cultured intellects, chastened affections, and costly hopes.”14 Based on her work and her religious commitments, we can assume these ideals served as a model for Dr. McDonald.

A useful contribution

When The Mary Baker Eddy Library asked me to mark the occasion of 35 years since the publication of Jean McDonald’s article, I agreed that recognition was appropriate and overdue. I felt it should convey both the intellectual rigor natural to scholarship and a sense of the spirituality fitting for a church. I noted that her career is a testament to how intellect and spirituality need not be seen as at odds but in fact can support one another.

In scholarship, books—not articles—tend to control the historical narrative. Occasionally, though, the reach of an article is unusual, its content particularly meaningful or influential. Dr. McDonald’s article fits this category. She represents a very small number of Christian Scientists whose religious practice has led them through adversities into an outward-facing, long-term, dedicated ministry of rigorous scholarship, published in professionally demanding, peer-reviewed venues, where it has entered the stream of scholarly discourse. As Dr. Kilde notes, her work “is still quite eye-opening.”15 Dr. Bednarowski calls it a work of “depth and prescience.”16 It recorded the substance of early Christian Science lives and theological commitments, in creative ways that still echo today.

Dr. Amy B. Voorhees is an independent scholar, historian of Christian Science, and the recent author of A New Christian Identity: Christian Science Origins and Experience in American Culture (University of North Carolina Press, 2021).

- Jean Angela McDonald, “Mary Baker Eddy and the Nineteenth-Century ‘Public’ Woman: A Feminist Reappraisal,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, Spring 1986, 89–111.

- Jeanne Halgren Kilde, personal communication, 7 September 2021.

- McDonald, “Mary Baker Eddy and the Nineteenth-Century ‘Public’ Woman,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, 108.

- Mary Farrell Bednarowski, personal communication, 12 September 2021.

- Here she is quoting the scholar of women in science Vivian Gornick.

- Jean Angela McDonald, Mary Baker Eddy at the Podium: The Rhetoric of the Founder of the Christian Science Church, MA thesis, University of Minnesota, December 1969.

- The chart shows 180 public speaking events between 1862 and 1903, mostly in the 1880s, with fewer during the years in which Mrs. Eddy focused on revising her book and reorganizing her church.

- Jean Angela McDonald, “Rhetorical Movements Based on Metaphor with a case study of Christian Science and its rhetorical vision, 1898–1910” (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1978), 13.

- Jean McDonald, “Rhetorical Movements Based on Metaphor,” 220–221.

- Jean McDonald, “Rhetorical Movements Based on Metaphor,” 260; see “Pocahontas employs Christian Science effectually in saving Captain John Smith,” Life, 23 February 1905, 221.

- Pamela Klassen, Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing and Liberal Christianity (Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2011), 76. For a treatment of this tendency, see Amy B. Voorhees, A New Christian Identity: Christian Science Origins and Experience in American Culture (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 184–186. Klassen calls this strategy “heathenizing” Christian Science.

- Mary Baker Eddy, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 130, 235.

- Mary Baker Eddy, Science and Health, 195; Mary Baker Eddy, Pulpit and Press (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), vii.

- Mary Baker Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings 1883–1896 (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 204, 356.

- Jeanne Halgren Kilde, personal communication, 7 September 2021.

- Mary Farrell Bednarowski, personal communication, 12 September 2021.