What’s the background on Eddy’s references to “the emigrant”?

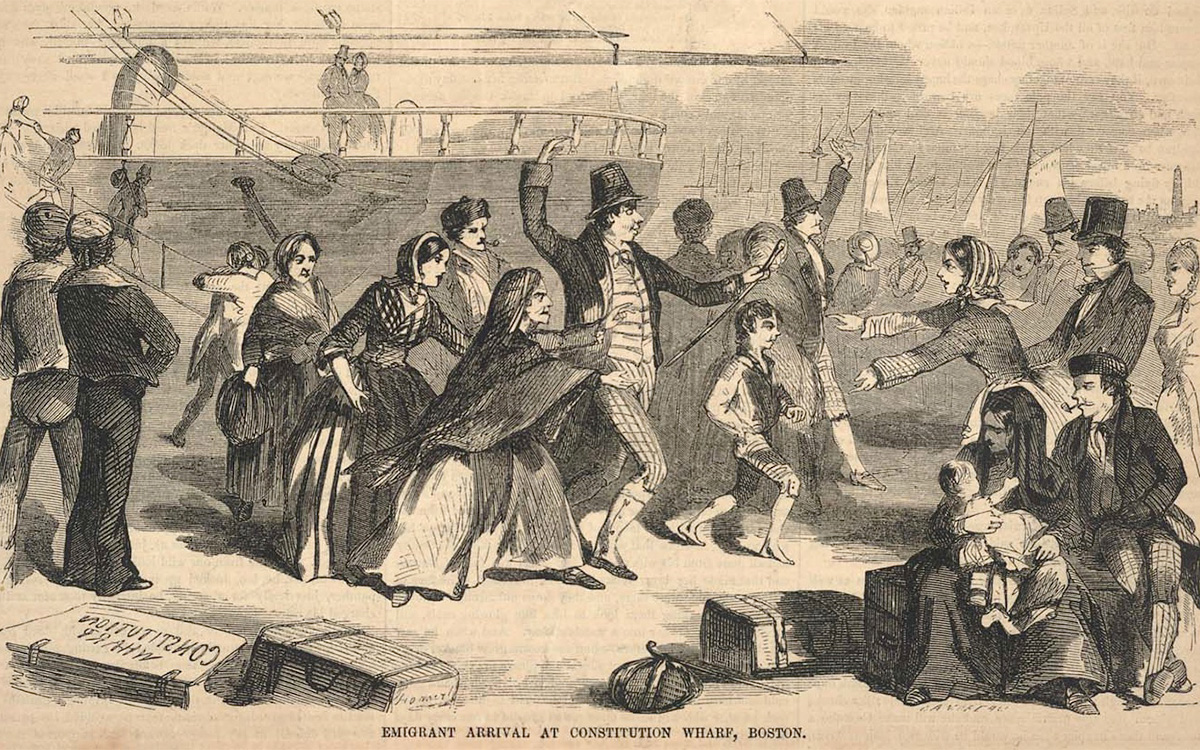

Wood engraving on paper: “Emigrant Arrival at Constitution Wharf, Boston,” from Ballou’s Pictorial, October 31, 1857. Winslow Homer.

One of The Mary Baker Eddy Library’s important roles is to provide accurate, factual information about Mary Baker Eddy and the history of Christian Science. Sometimes misunderstandings occur without the help of important contextual information.

Along those lines, we have sometimes been asked about Eddy’s statement on page 383 of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, where she referred to “the emigrant, whose filth does not affect his happiness ….” Knowing more about the circumstances surrounding this remark may help readers appreciate her choice of words.

The years 1820 to 1880 marked the “first wave” of mass immigration to Boston. The majority of immigrants were from Ireland, with smaller numbers from England, Scotland, and Canada, increasing the city’s population by 400 percent during those decades. By mid-century, these newcomers were settling in the South End and West End neighborhoods of the city, as well as in Cambridge, Charlestown, and Lynn.1

In an 1847 article in The Covenant magazine, “Erin, the Smile and the Tear in thine Eyes,” Eddy wrote sympathetically of the Irish:

When Burke and Berkeley are forgotten; when the name of Emmett shall cease to be spoken; when the last thunder-tones of O’Connell shall have died along the shore of the sweet isle of the ocean, then may Ireland be accused of want of intellect. . . . It is not that the Irish are naturally indolent, that their condition is thus wretched; and in proof thereof we have only to look at the rail-roads and canals that checker our country, wrought by Irishmen, who were driven cruelly from their native land, by abject poverty. Compelled to pay rent for that which is his own by right, taxed for the support of a government which does little else but multiply his wrongs, tithed for the support of a ministry he cannot hear preach,—he is kept like the drowning man who inhales the fresh draught, but to struggle, and sink, and rise and sink again.2

Many immigrants were trapped in extremely challenging living situations. Martin Lomasney, a nineteenth-century Irish ward boss in Boston, observed, “The great mass of people are interested in only three things—food, clothing, and shelter. A politician in a district like mine sees to it that his people get these things.”3

But many people did not “get these things.” Conditions in parts of the city of Lynn, where Eddy lived from 1864 to 1882, were dire. In 1874 the Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported on laborers’ housing in Lynn, Chelsea, Salem, and other cities in Massachusetts:

In a single building, . . . thirty-two feet long, twenty feet wide, three stories high, with attics, there habitually exist thirty-nine people of all ages. For their use there is one pump and one privy, within twenty feet of each other, with the several sink-spouts discharging upon the ground near by. . . .

In a locality recently inspected, the foul and broken sink-pipe of a tenement discharged its contents almost immediately into a well, from which the inmates of this and surrounding houses drew their water-supply, and which was also freely used by passers-by or those employed in the vicinity. To this well-water were traced nineteen cases of typhoid fever.4

It was from this milieu of inequality and resilience that Eddy wrote the passage that, in the final edition of Science and Health, noted “the emigrant, whose filth does not affect his happiness ….”

Here is the evolution of the statement, which first appeared in the 1st edition (1875):

Bathing and brushing to remove exhalations from the cuticle, receive a useful hint from Christianity, and another from the Irish emigrant, who is in health, although in filth; showing that the physical must correspond with the mental. When dirt gives no uneasiness, body and mind are equally gross, and the result is not so chafing.5

Eddy revised the statement for the 3rd edition (1881):

Bathing and brushing to correct the secretions, or remove unhealthy exhalations from the cuticle, receive a useful rebuke from Christian healing, that makes not clean the outside of the platter, and a hint from the Irish emigrant, whose filth has not affected his health because of the correspondence of mind and body. To the mind equally gross, dirt gives less uneasiness.6

For the 16th edition, she substantially revised the statement:

A hint may be taken from the Irish emigrant, whose filth does not affect his happiness, when mind and body rest on the same basis. To the mind equally gross, dirt gives no uneasiness. It is the native element of such a mind, symbolized but not chafed by its surroundings; but impurity and uncleanliness, which do not affect the gross, could not be borne by the refined.7

Eddy made only minor textual revisions to the passage in subsequent editions of the textbook. The final edits appeared in 1907.

- “First wave of immigration 1820-1880,” Global Boston: https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/home/eras-of-migration/first-wave/

- Mary M. Glover, “ ‘Erin, the Smile and the Tear in Thine Eyes,’ ” The Covenant, September 1847, p. 409. The reference to being “tithed for the support of a ministry he cannot hear preach,” is probably a reference to the tax-supported Church of Ireland, which was Protestant. Irish Catholics, the majority, would not have been permitted by their church authorities to attend Protestant worship.

- Thomas H. O’Connor, The Boston Irish: A Political History (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1995), p. 122.

- Fifth Annual Report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (1874),” The American Scene: 1860 to the Present, ed. William J. Chute (New York: Bantam Books, 1966), 226–227.

- Eddy, Science and Health, 1st edition (Boston: Christian Scientist Publishing Company, 1875), 432.

- Eddy, Science and Health, 3rd edition, Vol. 1 (Lynn, MA: Asa G. Eddy, 1881), 248.

- Eddy, Science and Health, 16th edition (Boston: Eddy, 1886), 354–355).