Who was Phineas P. Quimby?

By Keith McNeil

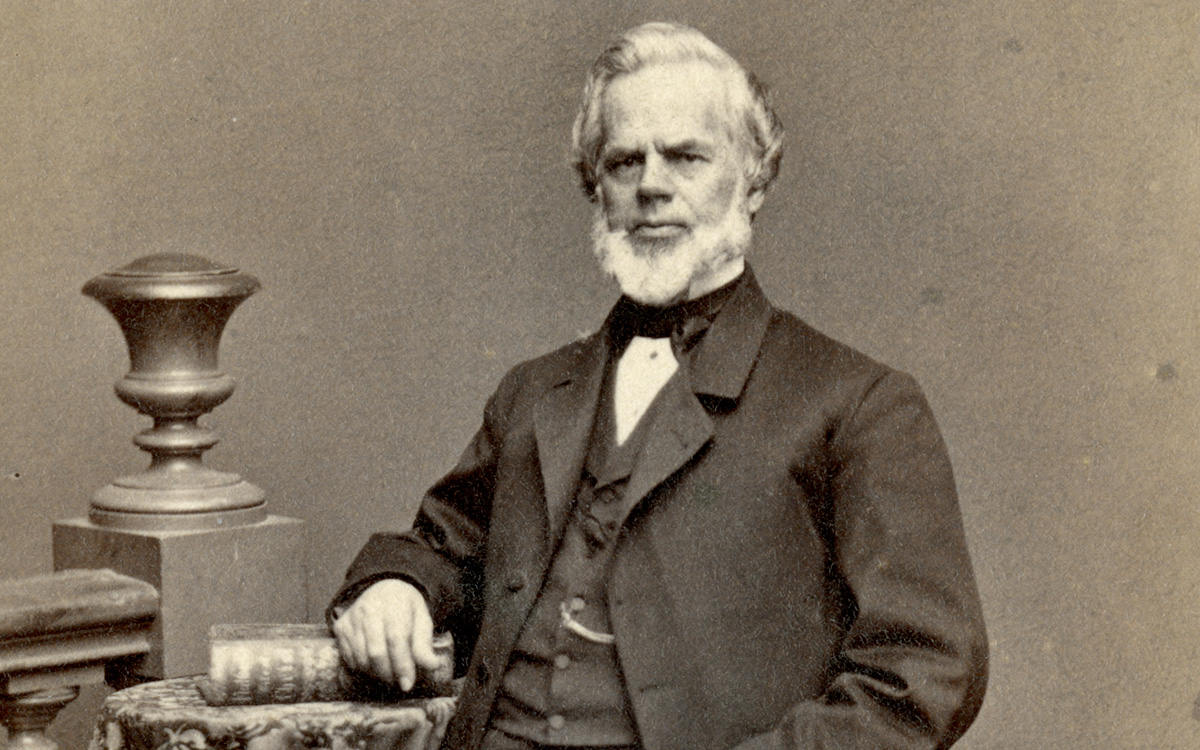

Phineas P. Quimby, c. 1861. T. R. Burnham. P01483.

Phineas Parkhurst Quimby (1802–1866) was a non-medical practitioner, known for his impact on what came to be known as the New Thought movement. One of the many historical questions about Mary Baker Eddy concerns what influence he did or did not have on her 1866 discovery of Christian Science and her subsequent publication of Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.

An in-depth examination of all the original Quimby papers, and the resources of The Mary Baker Eddy Library, shows that Quimby and Eddy shared an association over several years that was very meaningful to both of them. At the same time, it reveals that Quimby did not originate Christian Science.1

Background

In 1862, during a period of invalidism, Eddy traveled from Dr. William T. Vail’s Hydropathic Institute in Hill, New Hampshire, to Portland, Maine, where she sought treatment from Quimby.2 For the next three years she would see him periodically, and she regarded him as her mentor and healer. While she would continue to recognize his influence as a mentor into the early 1870s, she concluded that she could no longer support his materialistic healing theory and methodology, which by then she had left behind.

The debate over Quimby’s influence on Eddy effectively began in 1883, some 16 years after Quimby’s death; he had no personal input. Rather, his reputed “side” was represented by his son, George A. Quimby (1841–1915), as well as Julius A. Dresser (1838–1893), a former patient who claimed to speak on Quimby’s behalf. Initially, former Christian Scientist Edward J. Arens (1841–1905) also played a significant role.3 Eddy represented herself in this debate, assisted by her own followers. Thus from the start, Quimby’s life, career, and beliefs were seen through the lens of a highly partisan dispute.

The Dressers had moved to California after their association with Quimby. When they heard what Eddy and others were doing in Boston, they returned in 1882. Quimby’s copyist, Emma Ware, George Quimby, and Arens teamed up with Julius Dresser, who launched a public campaign in the Boston Post to claim Quimby as the source of Eddy’s Christian Science.4 5

The Dresser narrative

It is difficult to outline Quimby’s life without first examining several conflicting narratives. One was created by George Quimby, along with Julius Dresser, his wife, Annetta (1843–1935) and their son Horatio (1866–1954). It presupposed that Quimby was a master teacher and that everyone around him was a pupil, including Eddy, the Dressers, and New Thought author Rev. Warren F. Evans (1817–1889). A strong promoter of this narrative, Horatio Dresser would later write the most influential histories of Quimby and New Thought, presenting a Quimby healing theory and methodology that were artificially altered to make them appear to be closer in tone and language to the teachings of Christian Science. In fact, Horatio Dresser secretly doctored some of the Quimby documents in his 1921 book The Quimby Manuscripts, making Quimby’s theory appear less reliant on material means.6

The Eddy narrative

Eddy’s assertion was simply that Christian Science came from a Christian revelation in her life. She contended that her teachings differed dramatically from Quimby’s mesmeric techniques and theories, and that, despite her appreciation for him, he had had little impact on her later teachings.7 She explained:

He was neither a scholar nor a metaphysician. I never heard him say that matter was not as real as Mind, or that electricity was not as potential or remedial, or allude to God as the divine Principle of all healing. He certainly had advanced views of his own, but they commingled error with truth, and were not [Christian] Science.8

“He had a very inventive mind….”

Quimby (known as “Park” by his friends) was born in Lebanon, New Hampshire, on February 16, 1802. In 1888 his son, George, described his father’s life:

Owing to his father’s scanty means, and to the meagre chances for schooling, his opportunity for acquiring an education was limited. During his boyhood he attended the town school a part of the time, and acquired a brief knowledge of the rudimentary branches; but his chief education was gained in after life, from reading and observation. He always regretted his want of education, which was his misfortune, rather than any fault of his.

When he became old enough to go to work, he learned the trade of watch and clock making, and for many years after engaged in that pursuit. Later, before photography was known, he for several years made a business of taking a style of portrait picture known as daguerreotype. He had a very inventive mind, and was always interested in mechanics, philosophy, and scientific subjects. During his middle life, he invented several devices on which he obtained letters patent. He was very argumentative, and always wanted proof of anything, rather than an accepted opinion. Anything which could be demonstrated he was ready to accept; but he would combat what could not be proved with all his energy, rather than admit it as a truth.9

Quimby is confirmed to have been in Boston as early as 1826, working as a jeweler and watchmaker.10 He returned to Belfast, Maine, a year later to work with his brother William as a jeweler. Through about 1855 he filled many occupations, although his historical importance comes from a demonstrated interest in “animal magnetism” that became evident starting about the late 1830s.11 That theory began in part with Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815) and was popularized in America by Charles Poyen (?–1844), who first arrived from France in 1834 and was well-known by 1837 through the publication of his book Progress of Animal Magnetism in New England.12

Animal magnetism

Throughout the early 1840s there were many public exhibitions of animal magnetism (later called hypnotism). In them, a hypnotist would often place a professional partner, or subject, into a trance state or “magnetic sleep,” in which they would proceed to give clairvoyant readings. For example, the hypnotized subject might diagnose a disease and prescribe a cure, locate a hidden object, predict future events, or describe another person’s private experience to them. By 1843 Quimby was touring throughout Maine and other states with his subject, Lucius E. Burkmar. So successful were his exhibitions that one local newspaper, the Belfast Waldo Signal, called him the “Napoleon of Magnetizers.”13 By the end of 1847 he had left Burkmar behind, believing he could be his own clairvoyant seer.14

It is significant that, according to Quimby, his first thoughts about a possible mental side to illness started about 1833—far before his interest in animal magnetism began. For example, he wrote this in 1863:

Some thirty years ago [i.e., about 1833] I was very sick & was considered fast wasting away with consumption…. Having an acquaintance who cured himself by riding horse back, I thought I would try riding in a carriage as I was too weak to ride horseback…. I drove the horse as fast as I could go, up hill & down till I reached home & when I got into the stable, I felt as strong as I ever did.

From that time I continued to improve, not knowing however, that the excitement was the cause, but thinking it was something else.15

Probably sometime in the early 1850s, Quimby stopped putting his patients into a mesmeric trance.16 While it has been said that as a result he then left animal magnetism behind, that would incorrectly suggest that all practitioners of that theory induced trances in their subjects or patients, which was not true.

The basis of Quimby’s practice

By 1857 Quimby had moved his practice out of Belfast, to set up a healing office in Bangor, Maine.17 Likely about that time, and certainly before his move to Portland at the end of 1858, he printed his only extant flyer on his healing practice. It invited citizens to come see him when he visited their city. With its heading “To the Sick,” this was his only separately printed explanation of his healing methodology. The message stated that he would read the patient’s body and mind (clairvoyantly) and give a diagnosis of the problem. If the patient agreed with his diagnosis, that realization would change the “fluids” of the body and effect a cure.“The Truth is the Cure,” he stated. This was not a religious or metaphysical pronouncement but rather tied the “truth” of his diagnosis to the eventual cure, if the patient believed him. If Quimby could not clairvoyantly diagnose the problem, he said, he was powerless to help a patient.18

Here is an example of a letter that Quimby wrote to a patient in 1861:

. . . the winds or chills strike the earth or surface of the body[;] a cold clammy sensation passes over you. This changes the heat into a sort of watery substance which works its way to the channels & pours to the head & stomach. Now listen & you will hear a voice in the clouds of error saying, ‘the truth hath prevailed to open the pores & let nature rid itself of the evil that I loaded you down with in a belief.’ This is [the] way the God of wisdom takes to get rid of a false belief. The belief is made in the heavens or your mind. It then becomes more & more condensed till it takes the form of matter or truth. Then wisdom dissolves it & it passes through the pores & the effort of coughing is one of truth’s servants, not error[’]s; but error would try to make you look upon it as an enemy. Remember it is for your good till the storm is over or the error is destroyed. So hoping that you may soon rid yourself of all worldly opinions & stand firm in the truth that will set you free, I remain your friend & protector till the storm is over & the waters of your belief are still.19

In this letter we find a particularly important statement. According to Quimby, the thought of the patient was “condensed” until it became matter. He alluded to this in an 1865 document, looking back over his early years and experiments on his patients:

[The] experiments convinced me that man has the power of creating ideas and making them so dense that they could be seen by a subject that was mesmerized. So I used to create objects & make him describe them. At last I could take persons to all appearance in the waking state & make them see anything I chose. I found that I could stop persons while walking.20

Quimby believed that thoughts could be condensed into matter, so that an illness could be created by thought and therefore could be reversed by thought as well. He also held other unconventional beliefs. He contended that he took on the pains of his patients and then had to work to get rid of those transferred pains. He also maintained that the human mind could exist outside of the body, as seen in an early document probably dating to the mid-1850s:

This is the state of the mind in disease. The mind is driven from the body and dares not return to it…. I have labored harder to control the mind of a person in a diseased state than I ever did in performing any manual labor, in my whole life. I have spent hours of hard labor in mentally persuading the mind of a person to return to its body. This may seem strange to some, but it is true.21

In 1865 Quimby announced that he was moving back to his home in Belfast. He died there on January 16, 1866, at the age of 63.22

What his patients observed

The last people Quimby treated were a Mr. Clark and his wife, Jane, who had traveled from Kentucky in search of his help. Jane Clark made this affidavit many years following the incident she describes:

The following was his method of treatment: He placed both his hands in a basin of water; then the left hand upon the patient’s stomach and the right upon the top of the patient’s head, he slightly manipulated both the stomach and the head. The immediate effect was as if a hot iron had been placed upon the part and the sensation seemed to come from Mr. Quimby’s hands. I myself took two treatments from him for a longstanding complaint…. The treatments in Mr. Clark’s case were daily and continued from thirty to sixty minutes, during which Mr. Quimby would describe the patient’s symptoms more accurately than the patient himself could. After the treatment Mr. Quimby would go out to his barn, or garden, and work off the pain and disease from his own body, claiming that the treatment drew the disease from the patient into himself.23

According to the Clarks, Quimby used manipulation and standard mesmeric techniques for as long as he practiced.

Emily Pierce offered a different insight. She was the sister of Nelly Ware, a relation of Quimby’s associates Emma Ware and Sarah Ware. After describing methods similar to those mentioned by Jane Clark, she recounted this in an 1860 letter to Abby Pierce:

Yesterday he [Quimby] came again. He had no inclination ‘to talk Bible’ & could not approach me. He said there was no sympathy between us…. said I was unattractive & unhappy both of which statements I denied. I was never so happy in my life. It was evident he was waiting to be led & with a turn or word I could have misguided him.… The fact of it was I felt as if I influenced him as much as he me. By a change of expression I could bring out some opinion. I really tried to bring myself under his influence–submit without a word & accept all he says. The trouble is I say nothing, do not tell him all my pains & aches & feelings & then think he has told them to me. But if stories are true it matters little about accepting the theory. He heals without faith.24

Eddy’s connections with Quimby

City Hall, Portland, Maine, circa 1904. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-det-4a11956.

Quimby had some level of fame in his lifetime. But his historical recognition endures largely because of Eddy’s association with him. Known at that time as Mary Patterson, she was a partial invalid, having faced chronic illness most of her life. In October 1862 Eddy made her way to Quimby’s office in Portland and began treatments with him. Within a short time she found herself dramatically better and was even able to climb the 182 steps inside Portland’s city hall.25 She became a vocal supporter of Quimby in the local press. Early in November she wrote a piece for the local newspaper, effusive in its praise:

At present I am too much in error to elucidate the truth, and can touch only the key note for the master hand to wake the harmony. May it be in essays instead of notes, say I. After all, this is a very spiritual doctrine—but the eternal years of God are with it, and it must stand firm as the rock of ages. And to many a poor sufferer may it be found as by me, “the shadow of a great Rock in a weary land.26

Eddy would write to Quimby and visit him for the next three years. A review of her letters shows that she had continual physical problems throughout that time and often asked for his healing help. Nonetheless, it is important to note that she tended to downplay these problems and was instead laser-focused on the high point—the ability not just to walk but even climb to the top of Portland’s city hall. Being “raised from chronic disease” by Quimby (as she explained a few years later)27 was the critical point, rather than backsliding into previous conditions of illness, which she could dismiss as having been due to her own lack of understanding of the “truth.” We can see this in a poem she wrote less than a week after Quimby’s death, published the following month in a Lynn, Massachusetts, newspaper: “Rest should reward him who hath made us whole.”28

Distinctions between Quimby and Eddy

In the short newspaper excerpt above, we see Eddy noting several key points. First, she has made a clear differentiation between truth and error, not just in terms of metaphysics but also by allusion to the Bible.29 Second, while a number of assistants copied Quimby’s manuscripts, Eddy evidently only had access to some notes at that time. And third, Eddy’s religious background had led her to conclude almost immediately that Quimby’s was a “very spiritual doctrine”— which was not how Quimby described his own theories. Eddy saw Quimby through a Christian, biblical lens. In fact, her strong devotion to religion was already established, as is evident in this passage, written much earlier in an 1853 letter to her fiancé Daniel Patterson, concerning their opposing religious beliefs (she was a Congregationalist while he was a Baptist): “I have a fixed feeling that to yield my religion to yours I could not, other things compared to this, are but a grain to the universe.”30

Eddy was a Quimby champion while he was alive and remained one for a few years afterward. But by 1872 she realized a distinction between his healing practice and what she considered her 1866 discovery (as she would soon call it) of a Christian metaphysical reality, later explained in her 1875 book Science and Health.31 Hers was an idealism completely removed from Quimby’s beliefs as outlined here, including his belief that the human mind rather than the divine Mind, or God, healed. In no way did she recognize human thoughts as condensed into matter and becoming the cause of illness. She did not finally accept as actual the transfer of a person’s physical pain to the healer. Neither did she teach the reality of a human mind that travels outside of the body and needs to be coaxed back into it.

In an undated note, Eddy recounted her footsteps:

I had not found all that I desired in the Orthodox Church and I examined Spiritualism with utter disappointment Homeopathy was my last step in medicine and Quimbyism was my next in healing but here I found not Christianity yet I lauded his courage in believing that mind made disease and that mind healed disease Hence my loosened opinions took upward flight and I lauded Phineas P. Quimby as an advanced thinker and healer with my native superfluity of praise when praise was due.32

In the same article Eddy went on to describe what she came to see as an unbridgeable and significant gap:

Yet lacked I yet something the one thing needed and my health again declined Then came the [1866] accident and injury called fatal and the Bible healed me and from Quimbyism to the Bible was like turning from Leviticus to St. John in the Scripture and I forever dropped the thought that he had given even that the mind and human made disease and healed it — and gained the great rediscovery that God is the only healer and healing Principle and this Principle is divine not human. The remnants of Quimbyism took flight forever, and I struggled to wipe out all remaining faith in the power of human will to enslave me, or to deceive me into a false freedom. Turning from Quimby to the Bible for help in time of trouble was more marked than turning from matter to Spirit, from Leviticus to St. John in the Scriptures for the way of salvation.”33

Conclusion

Quimby was by all accounts a humanitarian, as well as a vigorous, inventive thinker. Eddy later wrote of him, “On his rare humanity and sympathy one could write a sonnet.”34 His manuscripts reveal a person deeply impelled to work out and record his own theories. Despite his apparent goal, however, he did not live long enough to publish those theories.35

Quimby certainly had a role in American history. And, while it is always difficult to determine exactly what influence one person has had on another, he likely influenced Eddy as she watched him working as a professional non-medical healer. But despite her early devotion to him, she had determined her faith in his theories to be misplaced. She later wrote this of her encounter with him:

At first my case improved wonderfully under his treatment, but it relapsed. I was gradually emerging from materia medica, dogma, and creeds, and drifting whither I knew not. This mental struggle might have caused my illness. The fallacy of materia medica, its lack of science, and the want of divinity in scholastic theology, had already dawned on me. My idealism, however, limped, for then it lacked Science. But the divine Love will accomplish what all the powers of earth combined can never prevent being accomplished – the advent of divine healing and its divine Science.36

Phineas Quimby was not what Mary Baker Eddy ultimately appeared to be searching for—a Christian spiritual healer who recreated the works of Jesus.

A graduate of Principia College, Keith McNeil has been an independent researcher and collector of materials on the history of Christian Science and New Thought for over 50 years. He published the three-volume book cited in this article, A Story Untold: A History of the Quimby-Eddy Debate.

- Prior to the publication of my three-volume book A Story Untold: A History of the Quimby-Eddy Debate (Carmel, IN: Hawthorne Publishing, 2020), no published study of that question had included an in-depth examination of all the original Quimby papers and the resources of The Mary Baker Eddy Library. That book is hereafter referred to as ASU.

- Julius and Annetta Dresser, diary entry, October 1862, Dresser, Julius and Annetta, Subject File, Mary Baker Eddy Library, hereafter referred to as MBEL.

- In late 1882, some time after breaking with Eddy, Arens began looking into Quimby’s beliefs and healing methods. He’d probably heard of Quimby from Dresser, when Dresser took a class on metaphysical healing from him.The Boston Post exchange between Dresser and Eddy in February and March 1883 may have contributed to Eddy’s decision, on April 6, 1883, to ask for a court injunction to stop Arens from printing and circulating a pamphlet in which he extensively plagiarized her. In his response, Arens took the position that Eddy had herself plagiarized her writings and ideas from Quimby. Arens was unable to prove his case, and on October 4, 1883, the court ordered Arens to stop circulating the pamphlet and that all remaining copies be destroyed (which was done on October 5, 1883). See Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings 1883–1896 (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 380–381.

- See “The True History of Mental Science,” Boston Post, February 8, 1883, 2, in which Dresser summarized a public lecture he had delivered two days earlier. Eddy responded in“Letter to the Editor,” which appeared in the Boston Post, February 19, 1883, 2. Dresser’s rebuttal appeared in “Letter to the Editor” Boston Post, February 24, 1883, 2. Eddy’s final “Letter to the Editor” appeared in the Boston Post, March 9, 1883, 2.

- Interestingly, just after Quimby’s death in 1866, Eddy had asked Julius Dresser to take up the mantle and be Quimby’s successor. He responded: “As to turning Dr. myself, & undertaking to fill Dr. Q’s place, and carry on his work, it is not to be thought of for a minute. Can an infant do a strong man’s work? Nor would I if I could” (Julius A. Dresser to Mary Baker Eddy, 2 March 1866, 632.64.008, MBEL).

- For a critical analysis of Horatio Dresser’s editorial bias and the minimization of Quimby’s materialism, see Robert Peel, Christian Science: Its Encounter with American Culture (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1958), 284. See also ASU, 28–30.

- Along these lines, historian Stephen Gottschalk observed, “Eddy may indeed have gained from Quimby a sense of the possibilities of mental healing; but nothing in Quimby accounts for the idea [of Christian Science] itself.” His conclusion: “It was not Quimby adapted or Quimby Christianized; it was simply a different idea.” See Gottschalk, The Emergence of Christian Science in American Culture (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1973), 130.

- Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings, 379.

- George A. Quimby, “Phineas Parkhurst Quimby,” The New England Magazine, Vol. 6, No. 33, March 1888, 271.

- The Boston Directory: Containing Names of the Inhabitants, with Boston Annual Advertiser annexed (Boston: John H. A. Frost and Charles Stimpson, Jr., 1826), 228.

- Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, The Quimby Manuscripts, ed. Horatio W. Dresser (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1921), 18–22. See also ASU, 530–536.

- Charles Poyen St. Sauveur, Progress of Animal Magnetism in New England (Boston: Weeks, Jordan & Co., 1837).

- Waldo (Maine) Signal, 23 November 1843.

- Dresser, Quimby Manuscripts, 46–50. See also ASU, 589–593.

- Dresser, Quimby Manuscripts, 28–29.

- Dresser, Quimby Manuscripts, 45.

- Dresser, Quimby Manuscripts, 32. See also ASU, 713fn.

- Dresser, “To the Sick,” Quimby Manuscripts, 150–151.

- Quimby to Mr. Sprague, 9 February 1861, Phineas P. Quimby Papers, Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, Boston University.

- Dresser, Quimby Manuscripts, 51.

- Dresser, Quimby Manuscripts, 184.

- Dresser, Quimby Manuscripts, 32–34.

- Jane T. Clark, affidavit, 22 January 1907, Quimby, Phineas Parkhurst – Affidavits, Etc. – Austin to Mullen, Subject File, MBEL.

- See ASU, 775.

- See Peel, Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Discovery, 2nd ed. (Boston: The Christian Science Publishing Society, 2022), 227.

- Mary M. Patterson, “What I Do Not Know, and What I Do Know,” Evening Courier (Portland, ME), 7 November 1862, 12, clipped in Mary Baker Patterson, scrapbook, n.d., SB001A, MBEL.

- Dresser, Quimby Manuscripts, 389.

- Mary Patterson, “In Memory of P. P. Quimby,” Lynn Reporter, 14 February 1866.

- See 1 John 4:6 (“Hereby know we the spirit of truth, and the spirit of error”).

- Mary Baker Glover to Daniel Patterson, March 1853, L08903.

- By 1872 Eddy forbade her students from using mesmeric techniques similar to those ascribed to Quimby. This is from the first edition of Science and Health: “We find great difficulties in starting this work right: some shockingly false claims are already made to its practice; mesmerism (its very antipode), is one. Hitherto we have never in a single instance of our discovery or practice found the slightest resemblance between mesmerism and the science of Life.”(Mary Baker Glover, Science and Health, 1st ed. [Boston: Christian Scientist Publishing Company, 1875], 5). See also ASU, 655–656.

- Eddy, n.d., A10409, MBEL.

- Eddy, n.d., A10409, MBEL. The contrast she drew was between Leviticus, the third book of the Torah in the Hebrew Scriptures, and the Gospel of John, the fourth book in the Christian New Testament.

- Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings, 379.

- Julius Dresser and Horatio Dresser posthumously championed Quimby’s theories, but, as biographer Gillian Gill stated in her 1998 book Mary Baker Eddy, “The evidence that Mary Baker Eddy’s healing theology was based to any large extent on the Quimby manuscripts is not only weak but largely rigged” (Gill, Mary Baker Eddy [Reading, MA: Perseus Books, 1998], 159).

- Eddy, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany (Boston: Christian Science Board of Directors), 307–308.