Women of History: Martha Matilda Harper

Listen to this article

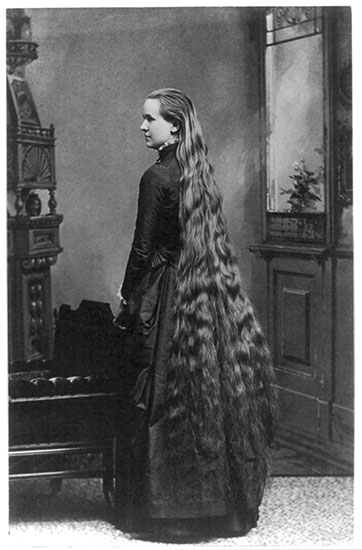

Photo of Martha Matilda Harper, circa 1914. LC-USZ62-76323 (B&W film copy negative.) Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

What could be more American than the business franchise? Popular restaurant, convenience store, and package delivery services are dominated by this model. Typically a parent company licenses franchisees to sell its products and use its branding, in addition to training and mentoring operators, who share a percentage of the profits.

Franchising owes a great deal to Canadian-American entrepreneur Martha Matilda Harper (1857–1950). Her hair salons, known as Harper Shops, changed the way women cared for their hair and navigated the evolving standards of grooming and beauty in the first half of the twentieth century. Like her African American counterpart, entrepreneur Madam C. J. Walker (1867–1919), Harper pioneered and defined women’s self-presentation in a rapidly changing world. She publicly credited Christian Science with healing her and sustaining her through decades in business.

Harper was born into poverty, in Munn’s Corners, Ontario, Canada. At the age of seven she started working for a relative as a domestic servant.1 A lack of means or formal education did not inhibit her, however; at age 25 she ventured alone to Rochester, New York, a center for social reform and business innovation. There she continued employment as a domestic worker for a wealthy family, using the same product to dress her employer’s hair that would launch her career—known as Moscano Tonique. She later claimed that this formula was given to her by a German-born physician on his deathbed.2

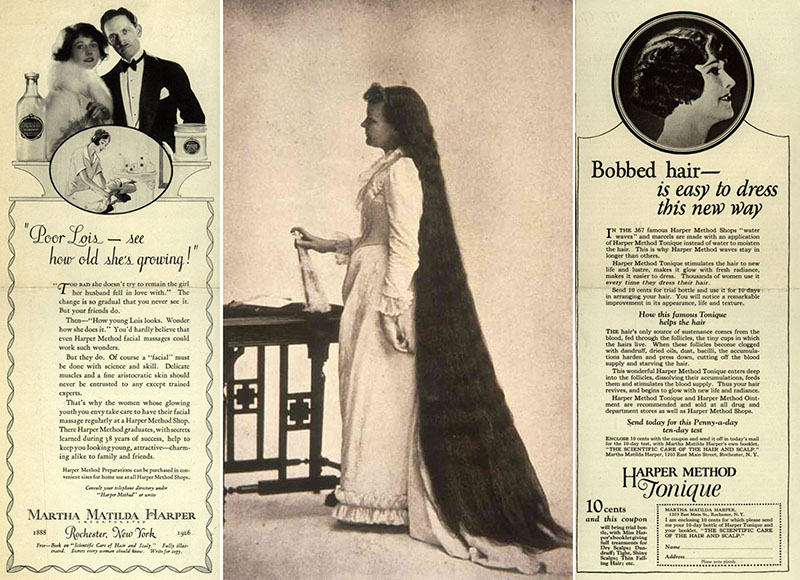

Advertisement for Harper Method Tonique, circa 1926.

In 1888, using her savings of $360, Harper opened a beauty salon in central Rochester. As the commemorative book Golden Memories later recorded, “She had her formula, her plan, and her two strong hands. She was ready to go.”3 This enterprise was a novelty; women at that time either cared for their own hair or employed hairdressers to visit them at home. But Harper’s salon was a success. Her clientele were primarily upscale, although she recruited employees from among Rochester’s domestic workers. She became the first female member of the city’s chamber of commerce and offered unusual incentives to customers that included child care during appointments and evening hours to accommodate working women.

The arduous task of establishing her business almost overwhelmed Harper, and the young woman became ill and unable to work.4 She had heard of Christian Science through her last employers, the Roberts family, and contacted Helen Pine Smith, a Christian Science practitioner in Rochester, appealing to her for help through prayer.5 A few days later, she was able to return to work. She continued to visit Smith regularly for some time afterward.

For the rest of her life, Harper maintained that this encounter with Christian Science marked a turning point in her life and career. In 1938 she prominently featured that story, with a picture of Smith, in a celebratory fiftieth-anniversary booklet about the Harper Method.6 Although she never became a member of The Mother Church in Boston, she joined one of its branches in 1897—First Church of Christ, Scientist, Rochester.7

Harper’s approach to beauty eschewed hair coloring and permanent waves. Instead it emphasized bringing out the natural beauty of customers. She embodied this ideal with her floor-length hair, featured in advertisements. Biographer Jane Plitt attributes that emphasis to the influence of Christian Science. Harper Method products were advertised in The Christian Science Monitor.

Photo of Harper salon, Rochester, New York, circa 1920s. From the Martha Matilda Harper collection. Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, New York.

On the other hand, as Harper developed her brand, she also emphasized facial, neck, and shoulder massages for customers. To facilitate the use of Harper’s products, her training school offered a complete course for operators of new stores. This included lessons in anatomy and techniques for treating the face, scalp, and hair. These emphases were less connected to Christian Science and, as Plitt admits, “Devout Christian Scientists might wince at Martha’s interpretations” of their religion—perhaps because of the perceived incompatibility of its spiritual basis with some of her methods. But Harper, like many others attracted to Christian Science, valued its emphasis on what Mary Baker Eddy described as “a higher and more practical Christianity, demonstrating justice and meeting the needs of mortals in sickness and in health” that “stands at the door of this age, knocking for admission.”8.

This passage, also from Eddy’s book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, may have resonated with her:

The term Science, properly understood, refers only to the laws of God and to His government of the universe, inclusive of man. From this it follows that business men and cultured scholars have found that Christian Science enhances their endurance and mental powers, enlarges their perception of character, gives them acuteness and comprehensiveness and an ability to exceed their ordinary capacity. The human mind, imbued with this spiritual understanding, becomes more elastic, is capable of greater endurance, escapes somewhat from itself, and requires less repose. A knowledge of the Science of being develops the latent abilities and possibilities of man. It extends the atmosphere of thought, giving mortals access to broader and higher realms. It raises the thinker into his native air of insight and perspicacity.9

Beginning in 1891 Harper expanded her business, when she introduced the franchising of Harper Method Shops.10 Most of these “Harperite” franchisees were women, many from modest backgrounds like their founder’s. They were trained in Rochester (and later in two additional locations), using The Harper Method Textbook. Courses lasted several weeks for experienced beauty operators and six months for neophytes. By the 1930s about 500 Harper Shops were located in the United States, Canada, England, France, and Germany.11 Harper is credited with inventing the reclining shampoo chair and shampoo basin, which are found today in almost every hair salon and barber shop. However—unlike Moscano Tonique—she did not patent them. The Harper Method attracted male customers, too, although its clientele remained primarily women.

In the 1930s, approaching age 80, Harper increasingly turned over management of the organization to her husband, Robert McBain (1882–1965). His new management team tried to update the Harper Method by including hair coloring and permanent waves in the services that shops offered. But they deemphasized the family feeling that had marked Harper’s relationship with her franchisees. Periodic gatherings at headquarters in Rochester and elsewhere had included banquets and garden parties that the women and their families universally loved. This changed atmosphere accompanied a strategy to make the business more competitive, but the new practices also made Harper products less distinctive. McBain sold the company in 1956. It operated under several names until 1972, when two buyers purchased its assets. One of them, Niagara Mist Marketing, Ltd., retained the formulas for Martha Matilda Harper’s original products.12 The original Harper Shop continued on, finally ceasing operations not long after the year 2000.

After McBain took over her business, Harper was not actively involved in it for the remainder of her life, due to declining health. In 1941 she withdrew from membership in the Christian Science church in Rochester for unknown reasons. Plitt remains convinced, however, that she continued to identify as a Christian Scientist.13

Listen to Martha Matilda Harper and the beauty of social entrepreneurship, a Seekers and Scholars podcast episode featuring author and scholar Jane Plitt.

- “Guide to the Martha Matilda Harper Papers,” Rochester (New York) Museum & Science Center, 2019.

- Ingredients in the Moscano Tonique later produced in Harper-owned facilities were listed as “Cantharides, Sage, Salt, Quinine and Alcohol 50% by Volume.” See Joanne Brokaw, “Martha Matilda Harper—Innovator in Beauty and Business,” Rochester Subway, 26 December 2015. http://www.rochestersubway.com/topics/2015/12/martha-matilda-harper-innovator-in-beauty-and-business/ accessed 4/27/2020; Jane R. Plitt, Martha Matilda Harper and the American Dream (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2000), 15.

- Golden Memories, 1938, Rochester, NY: Harper Methods, Inc.

- Golden Memories, 1938, Rochester, New York: Harper Methods, Inc.

- Helen P. Smith took Primary class instruction from Mary Baker Eddy at the Massachusetts Metaphysical College, in a class that began March 5, 1888. “The Students of Mary Baker Eddy,” The Mary Baker Eddy Library, https://www.marybakereddylibrary.org/research/who-took-classes-on-christian-science-with-mary-baker-eddy/ accessed 4/27/2020.

- Golden Memories, 1938, Rochester, New York: Harper Methods, Inc.

- Plitt, Martha Matilda Harper. A system of dual membership includes joining with The Mother Church in Boston and affiliation with a local branch church.

- Plitt, Martha Matilda Harper, 28; Mary Baker Eddy, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, 224.

- Eddy, Science and Health, 128.

- “Guide to the Martha Matilda Harper Papers,” 2019.

- A list “Authorized Harper Method Shops” is reprinted as back matter in Plitt, Martha Matilda Harper.

- Plitt, Martha Matilda Harper, 138–139.

- Plitt, Martha Matilda Harper, 133.