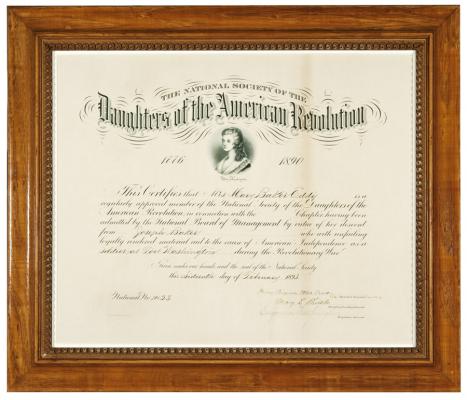

The National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (NSDAR) was founded on October 11. 1890. It came about at a time when women felt the need to express their patriotic feelings but were excluded from men’s organizations memorializing ancestors who fought for freedom and independence. A group of women in Washington, DC, formed the organization, which has since celebrated and advocated for patriotism. Since its founding, NSDAR has admitted over one million members. Mary Baker Eddy is National No. 1423.

Born less than 50 years after the end of the American Revolution, Eddy grew up hearing stories of Generals George Washington and Henry Knox. Her own grandfather and great-grandfather, both named Joseph Baker, had fought in the war for independence. She was therefore pleased when her old friend Martha Cilley (the daughter of one of her childhood ministers) wrote to her, inviting her to join the newly formed NSDAR.

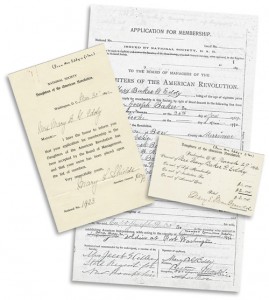

Copy of Mary Baker Eddy’s application for membership in the DAR, with acceptance letter and receipt for dues.

Cilley particularly hoped that Eddy would join. She had been tasked by Caroline Harrison, the wife of President Benjamin Harrison, to gain support among the women of New England for the new society. Eddy’s application—naming her patriot ancestor, great-grandfather Joseph Baker—was accepted in March 1892.

Two years later Eddy received a letter from fellow DAR member Effie Andrews, an ardent Christian Scientist. Andrews had heard that Eddy was a member of the DAR and wrote to her in November 1895, asking if she would like a DAR pin of her own.1 Eddy replied enthusiastically. “My dear Mrs. Andrews, Few things earthly could give me more pleasure than the insignia of the ‘Daughters’ which you named. I have longed to meet with them,” she wrote. “But I have so much to attend to that none else but I can do. I have to sacrifice all these worldly pleasures.”2

Andrews, who was no stranger to sending Eddy elaborate gifts, responded with an extraordinary display of generosity, in the form of an elaborately jeweled DAR pin. It arrived at Eddy’s home in Concord, New Hampshire, on December 21, 1895. Eddy’s thank you note, penned a few days later, was effusive:

At last I hail the moment to write and say. Your model par-excellence of beauty and love is a costly gift to me. But its chief value is not in Ruby and Diamonds but the heart that gave it…. Our names are inscribed together on your brilliant insignia of the DAR and your is inscribed on my heart as the Daughter in Science, Christian Science, of its Founder. Let them go down together in history….”3

D.A.R. membership pin with symbols of spinning wheel, set with 28 (2.44 CT.) diamonds. Blue enameled wheel with words: DAUGHTERS OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION. Hinged bale. J.E. Caldwell and Co. Jewelry Collection, 0.2568.1.

Eddy admired her pin. And she ended another letter to Andrews, written just a few weeks later, reiterating that fact. “My Insignia is admired by every one who sees it,” she wrote. “I almost think it was too costly, yet I only know it is above all price to me.”4 She wore her DAR pin in her Normal class of November 1898—the last class she taught.