Mary Baker Eddy’s designation of the Christian Science pastor

By Eric Nager

As the woman who founded Christian Science, Mary Baker Eddy wore many different hats during the 1880s. After establishing a church in 1879, she became its pastor later that year. She was continually revising her book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures,1 first published in 1875, to present an increasingly clearer view of her discovery. By 1883 she had founded the Journal of Christian Science2 and was serving as its editor. And among many other duties, she continued to teach classes on Christian Science.

Over time these responsibilities began to weigh on Eddy, as she struggled to find others with a sufficient grasp of and commitment to her revelation to help in the work. Perhaps most pressing was her desire that the success of Christian Science not depend solely on her. How could she optimally scale the growth of a new religion? While she did not have a definitive answer by 1889, she did take definitive—and unexpected—action, disbanding her church and moving from Boston to New Hampshire. One important aspect involves how she addressed the role of pastor in the church over the following few years.

Eddy knew that successful church structure was an important protection to the Christian Science movement. But she faced a dilemma, summed up in an 1888 letter to one of her students. “I cannot be Pastor and all else that I am required to be,” she wrote, later concluding, “The Church is our only sure foundation for the upbuilding of C.S. in the minds of the community.”3

Although Eddy disbanded the church, Christian Science services continued expanding. For example, the group in Boston continued as a “voluntary association,” without much change to its activities. During the 1880s churches had been springing up around the United States. In some areas, Christian Scientists wanted church services but found no one available to preach a sermon. By 1890, absent of any public guidance from Eddy, some had started experimenting—for example, a new church in Chicago: “Recognizing that Science and Health is both our Teacher and Healer, we resolved to take it into our pulpit and make it our Preacher also, by reading selections from it, together with appropriate passages from the Scriptures in place of a sermon.” The result was a doubling of attendance in that church and its Sunday School within two months.4

Likewise in Cleveland, congregations turned to the textbook. According to George Day, who was delivering sermons, “Some have separated themselves to make S&H their preacher, and seek to discard a church where a man is their pastor and ‘personal opinion’ the substance of the sermon.”5 He went on to wonder if a church under female leadership could be successful. Could using a book as a preacher be a way to get around the misogyny of the day?

Eddy had privately referred to her book as a preacher as early as 1890. “I believe it will be shown us that Science and Health is the best preacher with a student that loves and understands it,” she wrote to Hannah A. Larminie, a Chicago student.6 Indeed, it’s likely that one of the main reasons Eddy moved away from Boston in 1889 was to work on the 50th edition of Science and Health, one of its most significant revisions. She completed the work in 1891.

Even in the latter half of 1891, Eddy still continued to expect the use of preachers in her church. Writing in the Journal, she noted, “The time approaches when each church of Christ (Scientist) will call to the pulpit Christian Science pastors, properly equipped for this solemn office.” Importantly, she allowed that until there were enough people ready for this calling, churches could copy and read “my works” for Sunday services, provided that these copies were then destroyed immediately.7 How long that stopgap might be necessary, she did not say.

The quality of the sermons was at the forefront of Eddy’s thought. Clearly she felt that having the wrong person as a preacher could temporarily set Christian Science back in a given location. Referring to Sunday sermons in a 1891 letter to her student Caroline Frame of New York City, she wrote, “At present I would take them wholly from the Bible and Science and Health …. These preachers are sure not to mislead the thought and my students do in their sermons make some sad mistakes.”8

Part of the challenge for a Christian Science preacher was speaking through inspiration alone—every week. As Eddy counseled her Chicago student Ruth Ewing in 1894, “Every preacher of Christian Science should speak without notes.” She went on to say that it was acceptable to make notes of topical headings and place them on a desk or podium, at the same time maintaining that it was most important to “let God give you utterance.”9 The lack of preachers—and the challenge of finding competent ones (some pastors were trained ministers who had become Christian Scientists)—was impeding the spread of Christian Science churches.

The year 1894 was momentous, in that the original Mother Church edifice was under construction in Boston. As the time neared for the first service, Eddy sent instruction to the church’s directors: “God has spoken plainly to me that the Bible and Science and Health are to be the only preachers in this House of His.”10 At the time this applied only to The Mother Church. It was the first formal ordination of the two books as the pastor for a Christian Science church, and it has remained permanent.

Perhaps not yet willing to give up on the idea of a personal pastor, the Christian Science Board of Directors invited Eddy to become the “permanent pastor” of The Mother Church in March 1895—together with the Bible and Science and Health. In her response five days later, she declined, instead suggesting the title of “Pastor Emeritus” and explaining that, “through my book, your textbook, I already speak to you each Sunday.”11 On Sundays her “voice” was about to extend well beyond Boston.

Following the dedicatory services of The Mother Church, it did not take long for Eddy to ordain the pastorate of the books for all Christian Science branch churches in the world. The April 1895 Journal carried the announcement: “Humbly, and as I believe, Divinely directed – I hereby ordain that the Bible, and Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, shall hereafter be the only pastor of the Church of Christ, Scientist, throughout our land, and in other lands.”12 Finally, the problem of finding pastors to serve the churches was solved.

This did not mean that there were no rules or guidelines for the lay readers who would read from the Bible and Science and Health. In drafting the rules that applied to The Mother Church, Eddy was creating a template for all branch churches around the world. Among these was the request that the appointed readers would be a man and a woman; that they not read from copies, but from the books themselves; and that before the first reading from Science and Health in a given sermon, the book’s title and author be announced. Readers were to devote “suitable time” in preparing to read, and to remain “unspotted from the world.” In making these rules, Eddy acknowledged that the Sunday sermon was “a lesson on which the prosperity of Christian Science so largely depends.”13 14 The Directors adopted these rules in January 1895.

No sooner had Eddy ordained the new pastor for all churches than reports started coming back from the Christian Science field. A good example came from Sarah J. Clark in Toledo, Ohio: “While the Bible lessons have always meant so much to me, I am astonished to find the former study of them was not to be compared with the deeper meaning that comes from their study under the new dispensation.” She reported a growing congregation since the change.15 This must have been very gratifying to read!

Perhaps Lanson Norcross, who preached at The Mother Church in the 1880s, best summed up the reasons for ordaining the two books. In the August 1895 Journal, he cites four reasons for the change:

- doing away with personality in the pulpit

- giving Christian Science churches around the world one pastor (something unique within Christianity)

- creating unity and harmony of thought among the members

- serving to weaken rivalries within the church16

The last point was particularly meaningful to Eddy, who commended Norcross’s article.17 She had seen formerly loyal students break away from the movement before she disbanded the church in 1889.

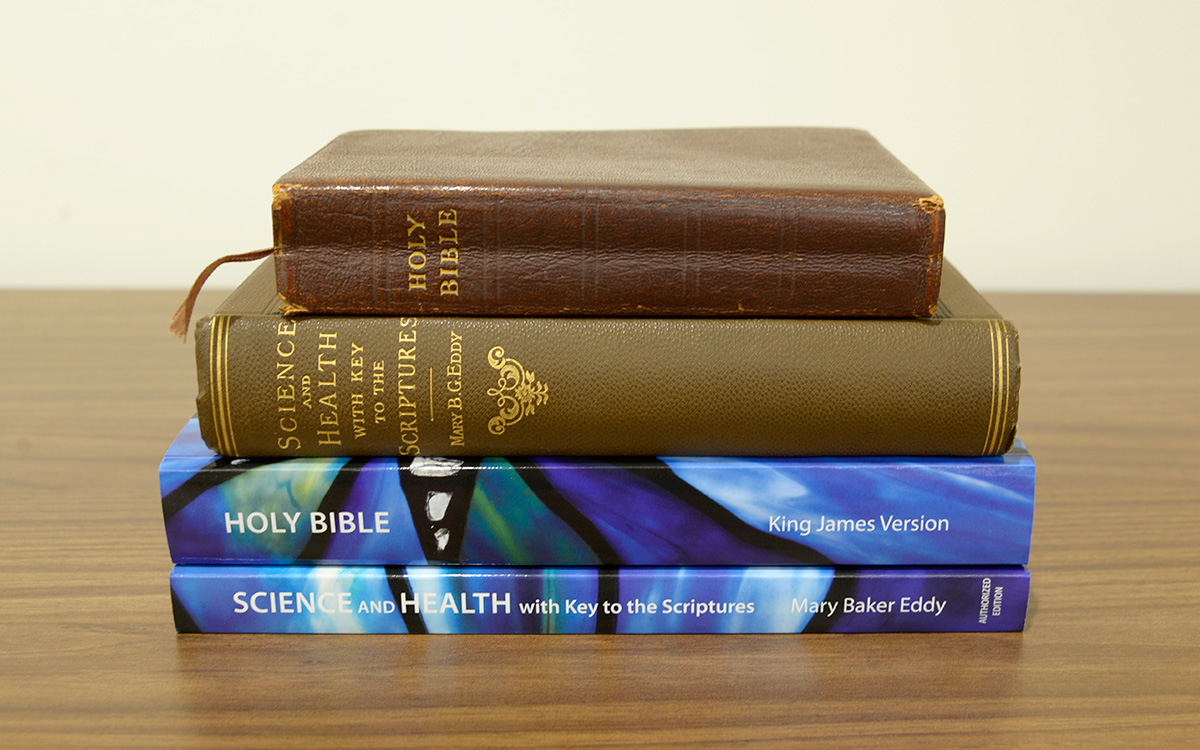

Other than Science and Health, the case can be made that nothing served to extend and grow the Christian Science movement beyond Mary Baker Eddy more than her ordaining the Bible and Science and Health as the church pastor. To this day, at every Christian Science church worldwide, an explanatory note is read from the Christian Science Quarterly at the beginning of every Sunday service. It begins, “Friends: The Bible and the Christian Science textbook are our only preachers.”

Eric Nager holds a master of liberal arts in history from Harvard University Extension and has taught as an adjunct history professor at Huntingdon College in Montgomery, Alabama. He served for 30 years in the US Army Reserve, in which his final tour was as Command Historian of the US Army Pacific. He currently works in the Treasurer’s Office of The Mother Church.

- This title was first used in 1883.

- Retitled The Christian Science Journal in April 1885.

- Mary Baker Eddy to unknown recipient, 24 September 1888, V01076.

- G. P. Noyes, “Church Service,” The Christian Science Journal, May 1890, 65. This is Eddy’s student Caroline Noyes; read more about her in the website article Women of History: Caroline Noyes.

- George Day to Lanson P. Norcross, 7 July 7 1891, 060a.17.058.

- Eddy to Hannah A. Larminie, 8 April 1890, L04501.

- Mary B. G. Eddy, “Advice to Students,” Journal, August 1891, 182.

- Eddy to Caroline W. Frame, 21 September 1891, L12815.

- Eddy to Ruth B. Ewing, 23 February 1894, L08507.

- Eddy to the Christian Science Board of Directors, 18 December 1894, L02747.

- See Eddy, Pulpit and Press (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 86–87.

- Eddy, “Church and School,” Journal, April 1895, 1.

- Eddy, “Rules of The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston,” 14 January 1895, L00663.

- As early as 1891, Eddy was expecting uniformity in church services. See Journal, December 1891, 365.

- Sarah J. Clark to Eddy, 18 April 1895, 050.15.038.

- See Lanson P. Norcross, “The New Pastor,” Journal, August 1895, 178–182.

- See Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings 1883–1896 (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 313.