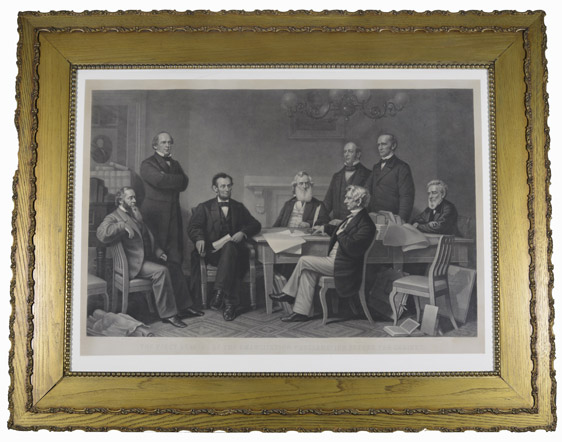

One of the two copies of “First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation,” by Francis Bicknell Carpenter, belonging to Mary Baker Eddy (0.2309).

The Emancipation Proclamation is one of the most important documents in the history of the United States. Written by President Abraham Lincoln in the summer of 1862, and announced in September of that year after the Battle of Antietam in the American Civil War, it went into effect on January 1, 1863.

While it is often believed that the Emancipation Proclamation freed all slaves in the United States, in fact it only freed slaves in the territories under control of the Confederate States of America. It didn’t free any slaves in the Union, although slaves who lived in Confederate states that came to be occupied by the Union army were emancipated. Additionally, the proclamation allowed African-Americans to join the Union army. In spite of the shortcomings of the Proclamation, it symbolized to many, including Mary Baker Eddy, the end of slavery, thus giving hope to millions of African-Americans. In a sense it also portrayed the Union army as liberators. This changed the focus of the war as not just about preserving the Union but also about the abolition of slavery.

To commemorate the publication of the Emancipation Proclamation, artist Francis Bicknell Carpenter (1830-1900) sought to depict President Lincoln reading it to his cabinet in September 1862. Carpenter described the publication of the document as “an act unparalleled for moral grandeur in the history of mankind.”1

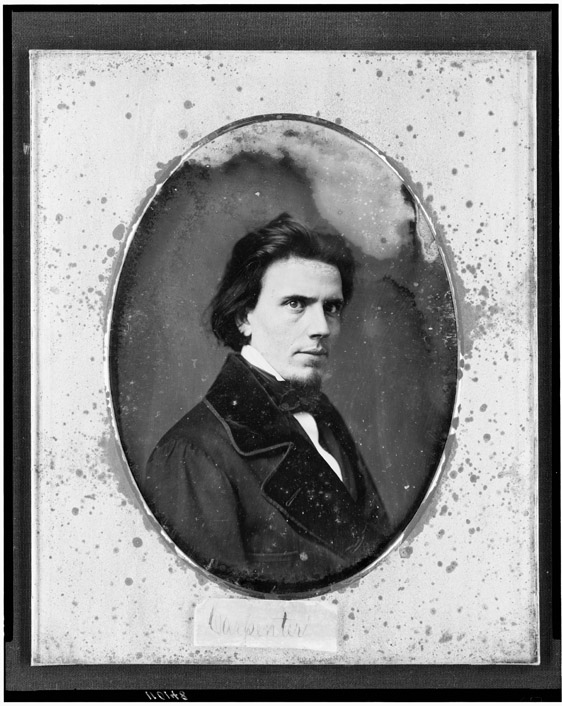

Francis Bicknell Carpenter (1830-1900), artist of “First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation” (Courtesy of the Library of Congress).

Carpenter was born in Homer, New York, in 1830. From a young age he showed a great talent for painting, and eventually moved to New York City, where he made his career as a portrait artist. He painted portraits of many politicians, including Presidents Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, and John Tyler. His most well-known painting, by far, was “First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation,” completed in 1864.

After his experience recreating the dramatic moment when Lincoln finished reading the proclamation to his cabinet, Carpenter recalled the inspiration for the creation. “There had…come to me at times glowing conceptions of the true purpose and character of Art, and an intense desire to do something expressive of appreciation of the great issues involved in the war.”2

Carpenter knew Schuyler Colfax, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Indiana. Colfax, in turn, put Carpenter in touch with Owen Lovejoy, an Illinois Representative. Lovejoy and Colfax then met with the President. He agreed to sit for his portrait, gave Carpenter access to his cabinet, and also provided him with studio space in the State Dining Room at the White House. Carpenter also utilized photographs by Civil War photographer Matthew Brady as a guide.

The completed oil painting of Lincoln and his cabinet is nine feet high by fifteen feet wide. Cabinet members portrayed include (from left to right) Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War (seated); Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of the Treasury; Gideon Welles, Secretary of the Navy (seated), Caleb B. Smith, Secretary of the Interior; William Seward, Secretary of State (seated); Montgomery Blair, Postmaster General; and Edward Bates, Attorney General (seated).

Carpenter had reasons for his placement of the cabinet members on the canvas. “Those supposed to have held the purpose of the Proclamation as their long conviction, were placed prominently in the foreground in attitudes which indicated their support of the measure; the others were represented in varying moods of discussion or silent deliberation.”3 Lincoln scholar Harold Holzer, however, points out something interesting:

The little regional irony here is that it actually doesn’t show the moment when Lincoln was reading the proclamation. He set it in his lap. It shows Secretary of State Seward gesturing rather grandly. So it’s really the moment when Seward tells him not to issue the proclamation: The timing isn’t right. So why on earth did Carpenter do this? … Well, Carpenter is from the suburbs of Auburn, N.Y., and William Seward is the hero of Auburn. So, you’ve got to get your local hero, your pride of place in this picture.4

Nevertheless, upon its completion, Lincoln remarked, “It is as good as it can be made.”5

After Carpenter finished the painting in 1864, it was shown for a short time in the White House and then in the U.S. Capitol building. Interestingly, it wasn’t until 1877 that New York philanthropist Elizabeth Thompson purchased the work from Carpenter and offered it as a gift to the nation. Congress held a joint session on February 12, 1878 (Lincoln’s birthday), and accepted the painting. It now hangs in the Senate wing of the U.S. Capitol.

The painting proved to be quite popular with the public. After Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, he was exalted as a great leader, and the Emancipation Proclamation was seen as one of the crowning achievements of his life. To possess a copy of the print helped Americans memorialize a great hero who had fallen before his time. Initially the publisher Derby and Miller created engravings, sold by independent salesmen and through the mail.

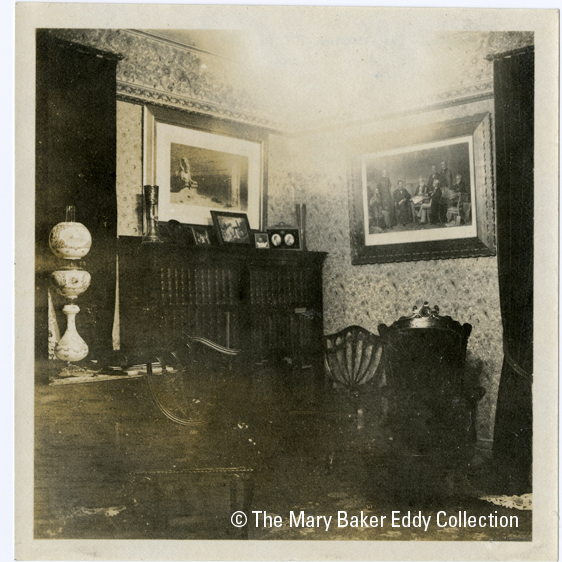

In 1866 the engraving was reissued by a New York City newspaper, The Independent, ”with copies going to tens of thousands of subscribers.” Eddy’s two copies of the etching are from this source. Both hung in different rooms at her Pleasant View house in Concord, New Hampshire, and her Chestnut Hill house in Newton, Massachusetts. One photograph in our collection shows a copy of the etching hanging in the library at Pleasant View. Another photo shows it on the wall in a sitting room reserved for the women workers at Chestnut Hill.

“First Reading of the Emancipation Proclamation” (1864) on the wall in the library at Pleasant View (P06306).

We don’t know how Eddy came to own the prints (or why, for that matter, she had two copies); we do know that she had a longstanding admiration for Lincoln. Her published articles and poems at the time of his presidency reveal her support for him.

Eddy was brought up as a Jacksonian Democrat (a supporter of President Andrew Jackson, who believed in more individual rights for the common man). She later became a supporter of the abolitionist cause, likely due to her experiences living in the Carolinas and seeing the treatment of slaves. A published account of an 1864 lecture she delivered titled “The South and the North” describes her life in South Carolina and speaks of “instances of the barbarous workings of the slave system.”6

Following the surrender of Fort Sumter to Southern forces in 1861, Lincoln first called on the loyal states for volunteers to fight the Confederacy. An 1863 request from the governor of New Hampshire, Eddy’s native state, asked for volunteers to fill Lincoln’s quota. This prompted her to write a published poem urging her fellow New Hampshire residents to enlist and “join the onward march of truth–’tis freedom’s hour.”7

From a published essay we learn that Eddy was no “Copperhead”—as the northern Democrats who opposed the war were called. In one 1863 piece, “Wayside Thoughts,” she wrote of her opposition to slavery and those who would keep others from being free:

“The dearest idol I have known,” molded into wrong, injustice, and the hydra-headed tyrannies of copperhead identity, binding with cold manacles the warm palpitating current of humanity, holding capital the free-born individual right, belittling the soul,—in the dignity of offended justice I would tear it from its throne and worship at a holier shrine.8

In two poems published near the end of 1865—the year the war ended—Eddy wrote of “Shades of our heroes! the Union is one,”9 and lamented the assassination of “our loved Lincoln,” who was murdered soon after the war’s conclusion.10

- Francis B. Carpenter, Six Months at The White House (New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1872), 10.

- Carpenter, 12.

- Carpenter, 14.

- “‘Emancipating Lincoln’: A Pragmatic Proclamation,” National Public Radio, accessed December 10, 2014, http://www.npr.org/2012/03/14/148520024/emancipating-lincoln-a-pragmatic-proclamation.

- Carpenter, 28.

- S., “The South and the North,” Waterville Mail, September 9, 1864.

- “Written on Reading the Call of the Governor of New Hampshire for Soldiers,” Portland Daily Press, December 12, 1863.

- “Wayside Thoughts,” Portland Daily Press, January 29, 1864.

- “Our National Thanksgiving Hymn,” Lynn Weekly Reporter, December 30, 1865.

- “To the Old Year 1865,” Lynn Weekly Reporter, January 13, 1866.