To best address this topic, we have reproduced an article on the topic by author and former Library Fellow, Paul Ivey. A brief biography of the author is also available.

Building Respectability: Christian Science Architecture in the U. S. A. and its Influence in Europe

Christian Science, a new American religion based largely in both Puritan and Transcendental strains of theology, was formulated by New Englander Mary Baker Eddy and organized as a denomination in the 1880s and 1890s, based on her discovery of a radical method of Christian healing found through a spiritual interpretation of the Bible—a science of Christianity.1

In 1875 in Lynn, Massachusetts, Eddy published the complete statement of this methodology in her book Science and Health. Through founding a church organized to reinstate primitive Christianity with its lost element of healing (1879, reformed 1892), and the Massachusetts Metaphysical College (1881-1889), her ideas began to be disseminated across the United States and by the 1890s in Europe. The organization grew rapidly and began attracting popular and critical attention in the secular as well as religious and medical press. In 1895 there were about 250 organizations, and by 1910 there were approximately 1100 congregations attached to the Mother Church in Boston.

In late 1894 the Mother Church of Christian Science was built in Boston. It was a Romanesque edifice built by Eddy as founder, and was similar to more traditional churches dotting the New England townscape. It was filled with symbolic stained-glass windows, many with women as their subject. A symbolic “Window of the Open Book” representing the City Foursquare from the Revelation of John dominated the program.2 By 1906, a massive extension of the Mother Church was built abutting the original church, in a grand renaissance classical revival style decorated with floral garlands and textual quotations from the Bible and Eddy on its massive walls (Fig. 1).3 This revealed a shift from the earlier more traditional figural symbolism and positioned architectural style and the Word itself as symbols for the new religion.4 The style of the immense church fit in with the more classicizing civic architectures defended by architects persuaded by the ideals of the City Beautiful movement, Swedenborgian Daniel Burnham’s civic reform movement that suggested that pure, rational architectural forms could reform not only the city’s physical fabric, but produce upright, efficient and moral citizens.

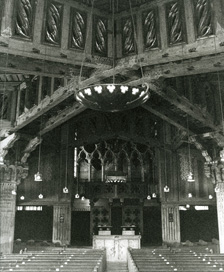

Architecture became the chief visible proclamation of Christian Science’s presence in American cities and towns, and also in Europe, where it grew rapidly in Great Britain and Germany after the 1890s. While early architectural ornaments and symbols in Christian Science churches were often taken from the traditional Christian iconography familiar to new Protestant converts to Christian Science, their more popular explanations were given metaphysical interpretations through the teachings of Christian Science. The dove, lambs and birds, as well as the seven-pronged candlestick that were carved in the Reader’s desks and decorative screen in Ramsey Traquair’s First Church, Edinburgh (1910) (Fig. 2), for example, were likely interpreted through their spiritual interpretations found in Eddy’s writings.5

Increasingly, however, most Christian Scientists turned directly to the Bible and Eddy’s writings for inspiration: the Word became their sacred decorations or declarations on the walls of their auditoriums. The words from the Psalmist, “He sent his word, and healed them (107: 20)” was taken quite literally by Christian Scientists. After all, Christian Science services consisted of lay Readers reading passages from a Lesson-Sermon: passages from the Bible with correlative readings from Science and Health that were believed to be divinely inspired. Bible texts and citations from Eddy’s writings were so commonly displayed on the walls, that she finally restrained their use.6

Fig. 2 (right): Interior, First Church of Christ, Scientist, Edinburgh. Courtesy of Paul Ivey

In the early 20th century, Christian Scientists began to practice a typically Protestant belief that had begun to fall out of favor with mainline Protestant churches, who were increasing their use of symbolic accessories: that figuration and even conventional symbols took away from the abstract and direct influence of thinking through the unmediated sacred Word.7 The Word, essentially, was viewed as a spiritual declarative medium, bringing into mental view spiritual ideas and substance. Eddy herself employed Christian symbols and metaphors in her writings. She wrote that, “Spiritual teaching must always be by symbols.”8 She preferred what one church official called “churchy church[es]” with “something pointing upward,” similar to her Mother Church and the one she donated to the citizens of Concord, New Hampshire in 1904, both of which had figurative windows with symbols.9 Nevertheless, the impersonality and unmediated quality of the Word trumped any consistent symbolization, other than the Cross and Crown registered trademark on the covers of Science and Health.10

Christian Science congregations generally eschewed any overt ecclesiastical symbolism by the 1920s, though stained glass windows, restrained ornamentation and even seven-pronged candlesticks and stars often had symbolic themes. Several churches used the seven-pointed star as a decorative symbol for Eddy’s seven synonyms for God from Science and Health: “. . .Principle; Mind; Soul; Spirit; Life; Truth; Love. . .”11 Certainly the “Glossary” in Science and Health underscored metaphysical definitions for scriptural words in the spirit of Swedenborg, suggesting many new possibilities for Christian Science symbolic representation. Sir Herbert Baker wrote that the building committee of Ninth Church, London (1928-30), after he completed the monumental 100 foot diameter auditorium for them, wouldn’t allow him to decorate save with a few sacred inscriptions: “the principles of the community were as antipathetic as those of Mohammedans to any representation of the works of the Divine Creator; nothing could be expressed but the inspired word.”12

In many ways, architecture itself became the primary symbol. When building their own churches, Christian Scientists looked to the Boston edifices as examples of appropriate architecture, though the Mother Church never had an official opinion on architecture. By 1907, debates about the appropriateness of the simplified classical revival style emerged in popular periodicals concerning the religion’s self-representation. Should Christian Science be associated with the timeless classicism of the past associated with primitive Christianity or with the more romantic Gothic style associated with historical and ecclesiastical Christianity?

Central to these debates was Solon Spencer Beman, who became the chief theorist of Christian Science architecture, whose classical revival churches were being built across the United States. By 1907, Beman had joined the Christian Science church and defended the classical style for which he was gaining popularity.13 To Beman, Christian Science represented a rational approach to spirituality, classicism oriented the denomination with the time of primitive Christianity, and the predominance of the classical in Christian Science commissions indicated that the church was progressive. Gothic architecture represented the past and the “ritualisms and [emotional ceremonies of the Orthodox Church].”14 When asked to help with the building of the Extension of the Mother Church, Beman minimized references to the mystical in favor of the rational: the Mosque of Ahmed I had been an eastern prototype for the edifice. Other American architects, such as Elmer Grey and William Purcell, believed that Christian Science architecture should rest on the democratic and local traditions of the individual congregations, and reflect the site-specificity and honest originality being supported by architects such as Louis Sullivan. Grey also felt that Christian Science should not “exclude from its architecture anything worthy in the Christian architecture of the past.”15

In many ways, the Columbian Exposition’s World’s Parliament of Religions that launched Christian Science into the public limelight, unlocked the silent and generally unfamiliar symbolism of eastern mysticism within the rational architecture of the White City. The classical style could be interpreted as the rational outgrowth of a Christian primitivism but it was equally associated with esoteric or specialized knowledge practiced by groups such as the Masons. Masonic interpretations of the Ionic column favored in many Christian Science commissions, for example, would suggest that they represented wisdom. While a penchant for Masonic symbolism was found in the decorative programs for several Christian Science churches,16 it is doubtful, even with Mrs. Eddy’s understanding and appreciation of Masonic symbolism, that most Christian Scientists discussed these interpretations openly.17 Most importantly to them, classical Christian Science architecture associated the religion and its adherents with a range of monumental buildings devoted to governmental, legal, and administrative functions, and many churches were sited close to new developing civic centers in an attempt to make them a legitimate part of future religious as well as architectural development.

While classical revival edifices made up the majority of church commissions in the United States between 1897 and 1925,18 the most architecturally celebrated Christian Science edifice was inspired by traditional Gothic architecture. It was designed by Bernard Maybeck, who modernized the style in his well-known Christian Science church in Berkeley, designed in 1910 (Fig. 3). Its poured concrete foundations and pillars with biblical narrative capitals, fir and redwood beams and trusses, medieval-looking glass placed in factory sashes, and painted stenciled decorations, expressed the unity, harmony, sincerity and honesty requested by the congregation’s building committee.19

In Britain, likewise, First Church, Manchester England, a striking expressionist Arts and Crafts design by Edgar Wood, was one of the most celebrated churches in Britain of any denomination, like the Maybeck church (Fig. 4).20 In 1903 the congregation hired Mr. Edgar Wood to be their architect, finding his work to be “most artistic and of a somewhat original character.”21 The church would be built in sections, and Lady Victoria Murray laid the cornerstone May 30, 1903. The stone was of Concord granite, from Eddy’s home state. This marked a new tradition: the cornerstones of British edifices, whenever possible, would be of New Hampshire granite. The façade presented a steep gable with a clear window shaped like a cross. The first section of the building was completed in April 1904, making it the first edifice erected for the purpose of a Christian Science church in England. The interior of the church was decorated with bronzed lettering for quotations on the walls, an Arabic organ screen, and beautifully carved chairs and Reader’s desks, the latter with doves descending, symbolizing divine Science. On the screen behind the readers was a symbolic cross, surmounted by a crown. A newspaper described the church as “one of the most strikingly original examples of architecture to be found, comprising a curious blending of ancient and modern, European and Eastern.”22Mrs. Eddy wrote to Murray that the “the architecture of your church is indeed suggestive and sweet.”23 The congregation replied to her, writing that “the building of this church has called forth spiritual qualities,—the sacrifice of material sense and self, and a greater sense of the unity of brotherhood,—all of which we know you will treasure more than any material structure.”24 The entire edifice was completed and dedicated in 1908. With its wings the shape of the church was like the inverted letter Y, said by a local newspaper to be symbolic “of the outstretched hands of love.”25

In Europe, the desire for respectability held sway. The church was growing rapidly and being openly criticized by both the clergy and the medical establishment as a new upstart American church, and represented what one newspaper called the “New World message.”26 By 1900, five congregations had organized in Hannover, Dresden, London, Edinburgh and Paris.27 In April 1903 Eddy founded Der Christian Science Herold.28 By 1910, there were over 55 congregations organized in English speaking countries, five in Germany, two in Holland and two in Switzerland, with smaller groups in Scandinavia and Italy. Growth remained dramatic in both English and German speaking countries over the next 20 years. In 1925 there were 22 congregations in Germany and nearly 150 churches and societies in Great Britain.

Christian Science churches built in Britain demonstrated a significant move towards the adoption of the American auditorium church plan or lecture hall, with congregants gathered around the dual pulpit used by lay Readers who perform church services. Architects focused on the need for excellent acoustics and commented on the American source of the auditorium church.29 Facades were characteristically non-religious, even somewhat eastern, but always respectable.

Christian Science came to Britain in 1890.30 Mrs. Eddy sent students to London, where fashionable West End women began to be attracted to it. By 1897, three years after the completion of the original Mother Church, the London congregation moved into an old Spanish Portuguese Jewish Synagogue. The members soon hired R. F. Chisholm to design them a new church edifice. Chisholm, having worked in eastern architectural idioms in India, provided them with what would have been a completely original Christian Science edifice (Fig. 5). A more traditional plan was asked for, and Chisholm provided them with a more traditional design, but one with some eastern elements and seven coupled windows across the façade (Fig. 6).

In 1904 the congregation laid their New Hampshire granite cornerstone. An architectural critic called the church an “Indian Reminiscence in Chelsea” and suggested that “one would not be surprised to see a Muezzin call the faithful to prayer” from the tower’s “lofty outlook.” He also told his readers that the “decorative details. . . are of an Anglo-Norman type well suited to the monumental character of the design” but, because it was a religion from America, “its projectors were under the influence of [Henry Hobson] Richardson, that architect who has invested American architecture with proportions almost Cyclopean.”31 The Architect and Contract Reporter thought differently: “The particular style of architecture for a Christian Science church should present no difficulties. The very early churches were mostly pagan temples converted into churches; when constructed as churches they exhibited many Eastern features,” implying that Christian Science was returning to the time of primitive Christianity, where both classical and Byzantine designs were historically located.32

Fig. 6: Elevation drawing for First Church of Christ, Scientist, London, 1908. Courtesy of Paul Ivey

By 1907, the Christian Scientists had grown in influence enough to interest over 9000 people to attend a Christian Science lecture delivered by American Bicknell Young in London’s Albert Hall. The idea that the acoustically perfected lecture hall or theater provided the best vehicle for Christian Science churches in Britain was henceforth continually suggested in the architectural press and demonstrated in several branch church designs: Byzantine styled Second Church by Sir John Burnett (1924-25); Lanchester and Rickard’s monumental Baroque Third Church (1910) in Mayfair, which included a lamp of wisdom in its elaborate entry cartouche surmounted by a tower of Wren derivation (Fig. 7); Paul Phipps’ modern Georgian Seventh Church (1926-29); and Oswald P. Milne’s simplified Georgian Eleventh Church (1925-27).33

One of the most prominent Christian Science commissions in Europe was First Church, The Hague (Fig. 8). By 1906, a group of Christian Scientists organized as a church in The Hague.34 By early 1920, the congregation was ready to build an edifice and by 1922, the church employed the internationally recognized “Amsterdam School” architect Hendrik Berlage to provide them with a church. Berlage represented a bridge between historical Dutch architecture and decoration, and the new Modern architecture then emerging in the United States and Europe, with its emphasis on structure and function in architecture. His First Church of Christ, Scientist in The Hague, designed and erected between 1924-1926, was built as a new architectural idea for a group that Berlage believed were rational and democratic thinkers representing a new American religion in his native Holland.

Berlage turned to examples of American church architecture, particularly Sullivan’s St Paul’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Cedar Rapids, Iowa (1910-1912) that he had visited on his 1911 tour of the United States, accompanied by architect and soon-to-be a Christian Scientist William Gray Purcell.35 He was particularly impressed that the church differed from traditional ecclesiastical architecture (that clung to the old forms of the Catholic church) in its emphasis on gathering the congregation in an “ideal community hall where everyone can see and hear the minister from every seat.” Sullivan created an “interior of his church [in] the form of a half circle and placed the tower above . . .[giving it] a higher ethical significance.”36

Purcell corresponded with Berlage about Christian Science in May 1918: “I think you will be interested to know that in America the new spirit has touched religion and produced a faith expressing itself with the simplicity of primitive Christianity but taking full account of modern intellectual equipment and world machinery. . . I connected myself with this body of spiritual workers shortly after I saw you last. . . I believe you would be interested in the type of citizens who are found associated with this movement, which is so essentially democratic in the broadest application of that word.”37 Purcell, who had worked with Louis Sullivan, was concerned with the proliferation of classical revival designs and expressed his strong commitment to modern non-historical principles in his 1926 Third Church of Christ, Scientist, Portland, which echoed a plan for a system of units to be built over time that he had recently addressed in an article in the Christian Science Monitor.38 He and Berlage subsequently shared plans.39

By 1922 Berlage had been invited to submit a design by the congregation.40 He was given a copy of Science and Health for his use during the design of the edifice. He apparently “found the concepts of man’s perfection appealing.”41 As one member put it, Berlage sought “by means of the construction of our church, to give figure to the ideal (of Science and Health)—the evolution of man towards perfection.”42 And certainly it was a challenge for him to create a church for a group that represented a new spirit in religion.

Berlage was asked to design a church to seat 700, with a Sunday School for 200 pupils, and a caretaker’s apartment.43 Het Haagsche Volk reported that the new church “consists of a combination of buildings. The church itself is placed on slightly rising ground. . . The walls of the church auditorium are quite plan. The rows of benches face the raised platform with its two readers’ desks.”44 The final church complex was made up of an assemblage of distinct geometric masses of different sizes and heights that legibly combined triangles and squares throughout the design. Each mass was clearly delineated for a specific function, making this one of Berlage’s most modern buildings.45 The Christian Science Monitor reported that this first Christian Science church in Holland would be one of the “chief modern architectural monuments of the Netherlands.”46

Berlage’s design followed Sullivan’s Cedar Rapid’s church, particularly with the tower placed at the apex of worship, soaring up above the Readers’ platform, and with seats for the congregants radiating out on a sloped floor, though not in as strict a semi-circle as Sullivan’s church. Architectural historian Leonard K. Eaton wondered if Berlage was simply “subconsciously reverting to the strong tradition of Dutch Protestantism as an amphitheater for preaching”47 but Het Haagsche Volk reported that the church, though unusual, “complies in every respect with the instructions received by the architect.”48

As architect H. Paul Rovinelli aptly put it, “The form of the church, in a more highly abstract and intellectualized manner, arose out of the delineation of the function, overlaid with a numerical and ornamental program drawn from Christian Science texts.”49 On the stairs to the auditorium was a quotation from the Revelation of John greeting the congregation as it entered into the services.50 Above the quotation was a ceiling mosaic of a lamb, not unlike those found in some British churches. In the auditorium, quotations from the Bible and Eddy were also present on the walls. On the ceiling was a skylight with a ten-pointed star. Architectural historian Sergio Polano suggested that in this church Berlage (together with De Stijl designer Piet Zwart) proved the mastery of “Dutch decorative geometricism.”51

Berlage had attempted a more traditional ornament of a cross and crown motif for the ceiling, and, though there were many examples to the contrary in branch churches throughout the United States and Europe, was told that Mrs. Eddy would have disapproved.52 Rovinelli states that nonetheless Berlage’s design was more subtle in its symbolism as it was based on “the use of numbers with symbolic significance in the Bible or Mrs. Eddy’s Science and Health: three, five, seven, ten, twelve, and forty.”53 The numerological significance of many of Berlage’s choices went un-acknowledged by the congregants, the esotericism of theosophy had been thoroughly attacked by Eddy in Science and Health, although by 1938 a numerological interpretation of Christian Science was being vetted by London Christian Science teacher John W. Doorly and his Zurich follower Dr. Max Kappeler. Berlage’s own interest in proportioning systems was strongly influenced by his theosophical colleagues.54

In the plain unornamented interior, orange, green and lilac glass blocks in horizontal and vertical bands in the auditorium created diffused lighting throughout the space, punctuated by the skylight. Berlage himself had suggested that “light from above was associated with the divine”55 and Purcell had advised Berlage “to flood the church with daylight, and with artificial light, as this religion stands for enlightenment as opposed to the dusky mysticism of the old theology.”56 The overall effect produced a “cool, restful character very much in keeping with the quiet nature of the Christian Science ritual.”57

Eaton noted that the Hague church was “the most striking evidence of the impact that Sullivan had on Berlage.”58 Other scholars have recognized multiple references to Wright’s Unity Temple, from skylights, to lamps and pulpit. To many the church “stands as a significant work illustrating the complex relationship between Berlage, Wright and rationalism.”59 Nevertheless, as the Het Haagsche Volk told its readers, the “building reminds one hardly in any respect of the traditional church edifice,” but “great satisfaction has been felt as the result of this experiment.”60

Certainly to the members of the European Christian Science congregations, even to those who experimented with more modernist designs,61 these church edifices reflected, whether with decorative symbols, quotations, or modern materials, the true definition of Church given to them in Science and Health: “The structure of Truth and Love; whatever rests upon and proceeds from divine Principle. The Church is that institution, which affords proof of its utility and is found elevating the race, rousing the dormant understanding from material beliefs to the apprehension of spiritual ideas and the demonstration of divine Science, thereby casting out devils, or error, and healing the sick. “62 As the members of the Hague church put it at the ceremony laying the cornerstone to their edifice: “This Church, ‘First Church of Christ, Scientist’, the first Christian Science temple in Holland, a symbol in stone of the spiritual building “The structure of Truth and Love,” is erected to the glory of God and in gratitude to Mary Baker Eddy, Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science.”63

Dr. Paul Eli Ivey is an Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Arizona where he teaches Modern and Contemporary Art and Theory. His primary research interests concern alternative religions in the American built environment. He received his Ph.D. from SUNY, Binghamton in 1992 and is author of Prayers in Stone: Christian Science Architecture in the United States, 1894-1930 (University of Illinois Press, 1999). He also contributed the essay “Solon Beman and the Metaphysics of Christian Science Architecture,” to the Chicago Architectural Club Journal, 10 and authored “Christian Science Architecture in the American City” in John M. Giggie and Diane Winston, Faith in the Market: Religion and the Rise of Urban Commercial Culture (Rutgers University Press, 2002). Dr. Ivey began using The Mary Baker Eddy Library to research Christian Science architecture in Britain as a Library Fellow in 2004 and recently published the entry on “Christian Science,” with help for the library’s researchers, in Peter Williams and Charles Lippy, Encyclopedia of Religion in America (CQ Press, 2010). He is currently working on completing a book length study of Christian Science architecture in the British Commonwealth and will work in the Library this summer.

Bibliography: Download Bibliography (PDF)

Footnotes:

1 See Gottschalk 1973; Gottschalk 2006; Gill 1998.

2 Armstrong 1897; Williamson 1939.

3 Eddy suggested that perhaps there shouldn’t be so many picture windows in the extension, since there were many in the original edifice. Williamson, 1939, 33. Williamson writes that there was “a general impression that all suspicion of symbolism was to be avoided,” but she was writing in the 1930s when most symbolism in Christian Science had been deemed inappropriate.

4 Jeanne Halgren Kilde explores the differences between the use of figurative images in the original edifice and the change to abstraction in the extension, with a specific gender component. See Kilde 2005, pp. 164-197.

5

6 See Eddy 1913, pp. 213-214.

7 See Smith, 2006. Smith argues persuasively that many of the common features found in mainline Protestant churches today, including the crosses, candles, sanctuary flowers, stained glass, and Gothic architectures, were appropriated directly from Roman Catholicism.

8 Eddy, 1875, final revision 1906, 575. back 9 Farlow 1905, pp. 33-47.

10 The larger coronet crown reminded many of the motif used by the Masons. It was featured on the cover of Science and Health from the 3rd edition from 1881, and in the decorative programs of many early branch churches, until it was replaced by a smaller crown in 1908. On symbolism see Beasley 1952, 77-78. The Christian Science Journal, 26, 186 explained that Eddy wanted the “Christian Science seal” to be “truly emblematic of what it stands for,” stating that the “crown now used is what is known in heraldry as a celestial crown, whereas the one formerly used was in fact not a crown at all, but a coronet, and possessed no significance when combined with the cross. The celestial crown, or, as it is sometimes called, the Christian’s crown, is the one described in Revelation, and it always has been emblematic of the triumphant life of the saints and martyrs.”

11 Eddy 1906, 587. See Ivey 1999, 159, endnote 43.

12 Baker 1944, 154. Ninth church, partly through the influence of building committee leaders Viscount and Lady Astor (the first woman in the House of Commons), was able in only four years to build a church within a few hundred yards of Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament. See “The Building of Ninth Church of Christ, Scientist, London, England, Report for Members’ Meeting, November, 1930,” unpublished manuscript, organizational archives of the Mother Church. The church was designed and built in 1928-30 in a simplified style that architectural historian Nicholas Pevsner called Early Christian. Baker, who was working on his plan for the Indian capitol at Delhi, designed the church, which he took on as primarily an acoustical problem. Hope Bagenal was the acoustical consultant. Bagenal 1927, pp. 727-28. On Ninth Church see Braithwaite 1931, pp. 806-09.

13 Beman 1907, pp. 582-590.

14 Beman 1907, pp. 587-588.

15 Grey 1907, 43.

16 For example see the classical churches of California architect Carl Werner, a Mason and architect of the Oakland Masonic Temple (1925). He designed Fourth Church, San Francisco (1913), and Fourth Church, Oakland (1922) among others and included low-relief braziers and flaming lamps of wisdom across his facades. Many churches at this time, including the extension of the mother church, had heraldic, symbolic, even Masonic references in their decorative elements. The cross and crown in windows, carvings and terra cotta tiles, sheaves of wheat, vines, individual fruits like pomegranates, lamps of wisdom, braziers of the temple, shields, all can be found in the decorative programs of many early Christian Science churches.

17 See Eddy 1896, pp. 142-143; Eddy 1913, 351. A Church Manual by-law (43rd edition, Article XXVI) requiring members to be free from other organizations at first excepted Free Masons. See also Christian Science Journal 22 (1904), 184. Some masons spoke out against Christian Science, see ‘Masons and Christian Science’, New York Times (May 18, 1904), 8.

18 See Ivey 1999.

19 See Bosley 1994.

20 Architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner wrote that this church was the “boldest religious building of the early [twentieth century].” Pevsner

21 Woodhead 1934, 33.

22 “Christian Scientists,” Manchester Courier, Jan. 4, 1908.

23 Woodhead 1934, 38.

24 Woodhead 1934, 40

25 ‘Christian Science, Extension of Manchester Church’, Manchester City News, (Jan. 4, 1908). ‘Christian Scientists, Origin and Growth of the Church in Manchester,’ Daily Dispatch Manchester” (Jan. 6, 1908). ‘Church of Christian Science’, Daily Telegraph (London), (Nov. 8, 1899).

26 ‘Church of Christian Science’, Daily Telegraph (London), (Nov. 8, 1899).

27 One public practitioner, Frances Thurber Seal, opened the Berlin Christian Science Institute by 1900 and began consolidating interested students throughout Germany. See Seal 1931.

28 This later became Der Herold der Christian Science. A couple of tracts had been prepared in French and Norwegian, and the April, 1902 Christian Science Sentinel had carried a German translation of a Christian Science lecture but this was the first official foreign language periodical.

29 See Kilde 2002.

30 J. S. Braithwaite 1931, pp. 806-9. On Oswald Milne’s Eleventh Church of Christ, Scientist, London see Fletcher 1927, pp. 309-15, with plans. See also Dixon 1908, pp. 178-183.

31 ‘The Stones of London, An Indian Reminiscence in Chelsea’, Evening Standard (London), (March 25, 1911). On the early central churches in London see Lessiter 2004.

32 ‘First Church of Christ, Scientist, Sloan Square’, The Architect and Contract Reporter, (August 19, 1910), 120. The church is now Cadogan Hall, a performance venue. Architect Paul Davis and Partners won a European Heritage award for its conversion. See ‘Chelsea church is reborn as concert hall’, Country life 199 (2005) 31, 32.

33 See ‘The Second Church of Christ, Scientist’, The Architectural Review, (August 1926), 63-73. Architectural historian Nicholas Pevsner called Third Church a “remarkably secular-looking front” like “the entrance to a prosperous insurance company.” Pevsner, 1957, revised 1983, 503. ‘The Seventh Church of Christ, Scientist’, The Architects’ Journal, Nov. 20, 1929. Fletcher 1927.

34 Growth must have been steady in Holland, but certainly not as dramatic as in English and German speaking countries. By 1910, another smaller Christian Science congregation had organized in Amsterdam, and two more congregations had formed by 1925. In 1925 there were 7 Christian Science Journal listed practitioners in the Hague; these were full-time workers who had entered into the healing ministry of Christian Science. The Bible Lessons, the centerpiece of the public Sunday worship service, published as the Christian Science Quarterly, had been available in Dutch since April 1917, and by 1924 the first translations of the religious article from The Christian Science Monitor appeared in Dutch. Mary Baker Eddy’s Rudimental Divine Science and No and Yes were translated in Dutch in 1928. Other publications followed: The Herald in Dutch began publication in January 1931 as did Eddy’s autobiography Retrospection and Introspection; and Science and Health was translated by 1951.

35 An account of his travels can be found in Eaton 1972, pp. 208-216. On other sources of possible influences, see Reinink 1970), pp. 163-174; and Singelenberg 1972.

36 Berlage 1912 in Gifford 1966, 609.

37 Polano 1988, 240.

38 This plan was probably inspired by an earlier project from 1914 for Third Church, Minneapolis that was never realized. Purcell 1925, 6. >

39 Correspondence quoted in Polano 1988, 240.

40 “Church History,” unpublished manuscript, organizational archives of the Mother Church.

41 Hosmer 1985, 335. According to Rovinelli 2001, a pamphlet by Eugenie Kohler, published by the church, also reported that Berlage had been given a copy of Science and Health. >

42 Quoted in Rovinelli 2001.

43 Berlage 1925, 487-490.

44 ‘Unusual Design in Hague Church,’ Christian Science Monitor, (Aug. 15, 1927), 7.

45 Rovinelli argues that the early sketches of the church held in the Berlage archive at the Nederlands Documentarie Centrum voor de Bouwkunst, Rotterdam, reveal a composition much closer to his Kröller-Müller hunting lodge, 1914-1920.

46 ‘Christian Science Church Being Erected at The Hague’, Christian Science Monitor, (December 8, 1925).

47 Eaton 1972, 219.

48 ‘Unusual Design in Hague Church’, Christian Science Monitor, (Aug. 15, 1927), 7.

49 Rovinelli 2001.

50 Hosmer 1985, 333-336.

51 Polano 1988, 240.

52 Rovinelli 2001 quoted Berlage at length on this point, “I thought with this I was finished, and used that symbol [cross and crown] as a center for the middle panel of the ceiling [in the sanctuary], so that the space would be illuminated in the night as well as in the day with artificial light. Various congregation members thought it a wonderful discovery, when suddenly from the ‘higher hand’–that is, from Boston–came the news that Mrs. Eddy had apparently once let it be known that she would not tolerate a single symbol on a Christian Science church building, as such a symbol would be in conflict with their belief. On this point I had of course to submit; but the logic escapes me why the obviously recognized symbol of a cross with a crown was acceptable on a Bible but not on a church. Berlage 1929, 70.

53 Rovinelli 2001.

54 Rovinelli 2001 points out that Berlage’s interest in the spirituality of sacred geometries was influenced by his colleagues J.L.M. Lauweriks, K.P.C. de Bazel and J. H. de Groot, “and thus contained an element of quasi-religious mysticism.” See Reinink 1972, pp. 455-472. On Doorly, see Brook 1973.

55 Quoted in Rovinelli 2001.

56 Quoted in Polano 1988, 240. The Christian Science Monitor took notice as well, and published an article concerning the making of the colorful glass bricks: ‘Glass Factory Making Bricks,’ Christian Science Monitor, (Dec. 6, 1927): “The hall where the services are held does not have ordinary windows, but receives its light exclusively through these glass bricks. The light streams in, evenly diffused through lone and rather narrow horizontal and vertical spaces, and gives and almost brighter appearance than ordinary windowpanes.”

57 Eaton 1972, 219.

58 Eaton 1972, 218.

59 Polano 1988, 26, 29.

60 ‘Unusual Design in Hague Church’, Christian Science Monitor, (Aug. 15, 1927), 7.

61 Another church with modern appointments was built in Amsterdam in 1938. See ‘First Church of Christ, Scientist, Amsterdam’, Bouwkundig weekblad architectura 59 (1938), pp. 147-152. In Switzerland Christian Science congregations turned to two of the Swiss pioneers in modernist architecture for their churches, O. R. Salvisberg’s First Church, Basel (1936), and Hans Hofmann’s [with Adolf Kellermüller (1895-1981)] First Church, Zurich, Switzerland (1938), during which time Hofmann was chief architect of the Swiss National Exhibition in Zurich. These architects were all associated with the Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, Hoffmann as student from 1918-1922, Salvisberg as a professor after 1930. See ‘First Church of Christ, Scientist, te Zurich’, Bouwkundig weekblad architectura, 66 (1948) 28, pp. 221-227.

62 Eddy 1906, 583.

63 “Church History,” unpublished manuscript, organizational archives of the Mother Church.