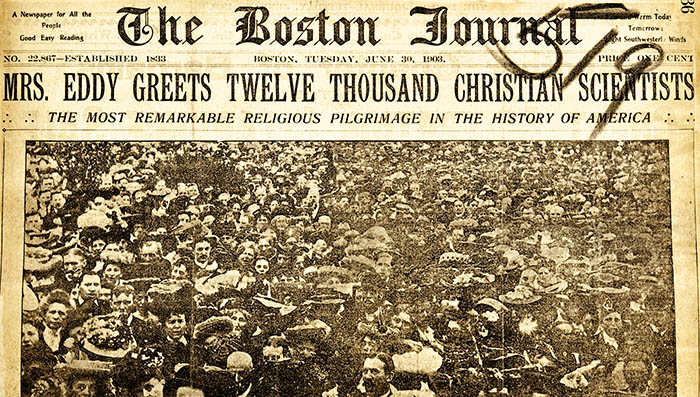

A front-page story in the June 30, 1903, Boston Globe tells about Mary Baker Eddy’s address on the previous day in Concord, New Hampshire.

In the late 1890s and early 1900s, June was often called the “Communion Season” at The Mother Church (The First Church of Christ, Scientist) in Boston. The year 1903 was especially memorable.

At the June 28, 1903, Communion services, Mary Baker Eddy extended an invitation to Christian Scientists to come to Pleasant View, her home in Concord, New Hampshire. The following day, throngs of people arrived in Concord. Many of them were able to see her and hear her give a brief address from the balcony.

Interest in the details of that day has only increased over the century following this unique event. For that reason we weren’t entirely surprised when, as preparations began for an open house at The Mary Baker Eddy Library in June 2012, a question was asked: Could we find any artifacts in our collections from Eddy’s 1903 address at Pleasant View? While it might seem like a simple project, we’ve found that this kind of exploration can actually be quite complex.

Fortunately, up-to-date museum collections management software allows curators, archivists, and researchers to record and access information in a more organized and accessible way than ever before. This vital information, giving the history of our documents and objects, provides the kind of meaningful context that assists researchers, scholars, and other visitors to the Library. In addition, the variety of resources available here is incredibly rich: original documents, newspapers, scrapbooks, firsthand accounts (reminiscences), photographs, artwork, and many different kinds of objects. For this project we also investigated our collection of Mary Baker Eddy’s clothing. All of these resources were carefully “mined” to bring new understanding to a story that was already familiar to many.

For example, there is much valuable information in the published photographs and news reports. The June 29, 1903, Concord Evening Monitor (2:00 p.m. edition) reported that the temperature at noon was just 68 degrees—quite cool for an early summer day. It had been cloudy with a trace of precipitation over the past 24 hours (though it was reported by people who were there that the drizzle had cleared by the time Eddy spoke in the afternoon).

The weather did not discourage too many people from making the trip, apparently, for the newspapers reported that as many as 10,000 to 12,000 were in attendance.

Alfred Farlow, whose work revolved around responding to the press on topics relating to Eddy and Christian Science, collected clippings from newspapers, and saved some of them in scrapbooks. These excerpts describe the events of June 29, 1903, as well as Eddy’s attire:

She wore a rich costume of violet, with a silk coat trimmed with lace medallions and appliqué. About her shoulders was a cape of white ostrich tips, lined with satin and with a long stole front. She wore white gloves and from her girdle hung a gold chatelaine bag. Her bonnet was of violet with ostrich tips of violet and white.1

Her gown was of royal purple velvet, trimmed in a lighter shade of the same material. A jacket of black was over a waist of white. Across the shoulders was thrown a cape of white ostrich tips dotted with black. Her bonnet was trimmed with purple and white.2

Over her shoulders was flung a magnificent ermine cape, fastened with silken ribbon, the ends of which reached the floor. A bright, colored bonnet, trimmed with violets, was on her head, and her dress was a navy blue silk, beautifully trimmed with ecru lace, and her hands were encased in white kid gloves.3

Another valuable piece of documentation is the series of images taken by a local photographer, W.G.C. Kimball. These are in our Historic Photograph Collection. John Lathrop, a member of Eddy’s staff, described the most famous image:

All are familiar with her balcony picture, which I consider the best picture of her that we have. At the time of the gathering of Christian Scientists at Pleasant View in June 1903. Mr. Kimball, the Concord photographer, asked to photograph Mrs. Eddy on the balcony. At first she declined, but afterwards said, if he would stand at a distance and not distract the visitors, he might take the photograph. This he did, and that was when the good likeness of our Leader known as the balcony photograph was taken.4

Looking at Kimball’s photograph, there is no question that Eddy was wearing her ermine cape, which is in our collections. The hat she wore is also there, and has been consistently documented as the one from her “balcony speech.”

We found that locating the other items of clothing that Eddy wore that day was not quite as easy. Our research began with a return to the newspaper descriptions, as well as other documentation. We consulted reminiscences of Christian Scientists who were present that day; only a few mention Eddy’s clothing. Ralph Moody gave one interesting description: “…Mrs. Eddy [was] robed in purple (the prevailing color of the season) with a mantle of white ostrich-plumes ….”5 Not surprisingly, most reminiscences concentrated on Eddy’s demeanor, voice, and words, as well as on her message. Emma Shipman remembered this:

We found that locating the other items of clothing that Eddy wore that day was not quite as easy. Our research began with a return to the newspaper descriptions, as well as other documentation. We consulted reminiscences of Christian Scientists who were present that day; only a few mention Eddy’s clothing. Ralph Moody gave one interesting description: “…Mrs. Eddy [was] robed in purple (the prevailing color of the season) with a mantle of white ostrich-plumes ….”5 Not surprisingly, most reminiscences concentrated on Eddy’s demeanor, voice, and words, as well as on her message. Emma Shipman remembered this:

I attended the last large gathering in Concord in June 1903, when Mrs. Eddy stood on the balcony and stretched out her hands so lovingly to the great congregation gathered on the lawn. Her ringing words at that time, imploring us to “trust in Truth, and have no other trusts” grow in import to those who follow her teachings.6

Dorothy Dellano Rumage had this recollection of the day:

There was no stir, just a joyous receptivity to our Leader’s message. Mrs. Eddy spoke quietly, but with great strength and spiritual conviction. Although microphones and public address systems were unknown at that time, every word was perfectly and distinctly heard. There was not the slightest apparent sign of the accumulation of years. Mrs. Eddy was erect, gracious, with great ease and activity of movement.

As she ended the address with the words “Trust in Truth and have no other trusts,” my parents said that they felt such a great sense of release and uplift….7

This oil painting is a color depiction of the event—although artist Jean Jacques Pfister completed his first oil portrait of Eddy in 1938, some 35 years after the gathering. Reproduction prints of this color portrait were sold in Christian Science Reading Rooms, and later through the catalogue of The Christian Science Publishing Society. It has become a well-known and recognized representation of Eddy. It shows her attired in a purple ensemble, wearing the ermine cape over her shoulders, and a bonnet also adorned with what appears to be ermine. Examining Kimball’s photograph and Pfister’s painting, we noted a bellflower that is part of the embroidered decoration on the skirt. Also clearly shown in each picture is a scalloped lace trimming that runs along the lapel of the bodice portion of the garment.

This oil painting is a color depiction of the event—although artist Jean Jacques Pfister completed his first oil portrait of Eddy in 1938, some 35 years after the gathering. Reproduction prints of this color portrait were sold in Christian Science Reading Rooms, and later through the catalogue of The Christian Science Publishing Society. It has become a well-known and recognized representation of Eddy. It shows her attired in a purple ensemble, wearing the ermine cape over her shoulders, and a bonnet also adorned with what appears to be ermine. Examining Kimball’s photograph and Pfister’s painting, we noted a bellflower that is part of the embroidered decoration on the skirt. Also clearly shown in each picture is a scalloped lace trimming that runs along the lapel of the bodice portion of the garment.

A search using the computer database helped us find a purple dress—but the trimmings and lace on the bodice were not the same as that photographed or painted. Our conclusion is that Eddy was apparently wearing the skirt, but not its matching bodice.

By comparing the lace details and the buttons evident in Kimball’s photograph, and nicely rendered in Pfister’s painting, we found that she was wearing a black silk faille jacket, which has an accompanying white silk brocade vestee (this may be the white waist mentioned in the Globe newspaper account).

Although Pfister’s oil painting is not entirely accurate, it did provide us with important clues. Working from Kimball’s black-and-white photograph, Pfister had interpreted the entire ensemble as purple…perhaps because that was one of Eddy’s favorite colors.

Eddy’s attire of June 29, 1903

Over the dress and jacket, she wore the ermine cape so well depicted in Pfister’s painting. Newspaper accounts described both Eddy’s cape and hat as being adorned with ostrich tips. However, neither garment contains any ostrich feathers. It is probable that, from a distance, the long mouton (curly sheep fur) stole in front of the ermine cape appeared to be ostrich feathers fluttering in the breeze.

We’ll conclude this case study with an excerpt from a letter by William P. McKenzie, a Christian Scientist who was present at the 1903 address. He wrote to a friend decades later, when sending him a copy of the Pfister painting:

I am sure you will be glad to have this picture in your house, because in a way of speaking, it is Mrs. Eddy’s own idea of herself…she put on heavy clothing which she felt would express the dignity of the occasion. She put on gloves which did not conceal the gracefulness of her hands, and as Mrs. McKenzie says, this is her picture of herself, since she posed for it…Otherwise, there might not have been any record of it, except the impression that was so wonderfully made upon all of us as we listened to her words, appreciated her grace, and felt the message burn within us.8

- Concord Evening Monitor, 29 June 1903.

- Boston Globe, 30 June 1903.

- Boston Evening News, 30 June, 1903.

- John Lathrop, “Some Recollections and Human Impressions of Mary Baker Eddy,” Reminiscence, 4.

- Ralph Moody, Reminiscence, 7.

- Emma Shipman, Reminiscence,19; See Eddy, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 171.

- Dorothy Dellano Rumage, Reminiscience, 1–2.

- SF – McKenzie, William P. and Daisette Stocking Papers – William P. McKenzie – Correspondence – 1934–1945.

![During Eddy's address, a photographer (in foreground) set up his shot. [P00105]](https://www.marybakereddylibrary.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/P00105forweb-239x300.jpg)