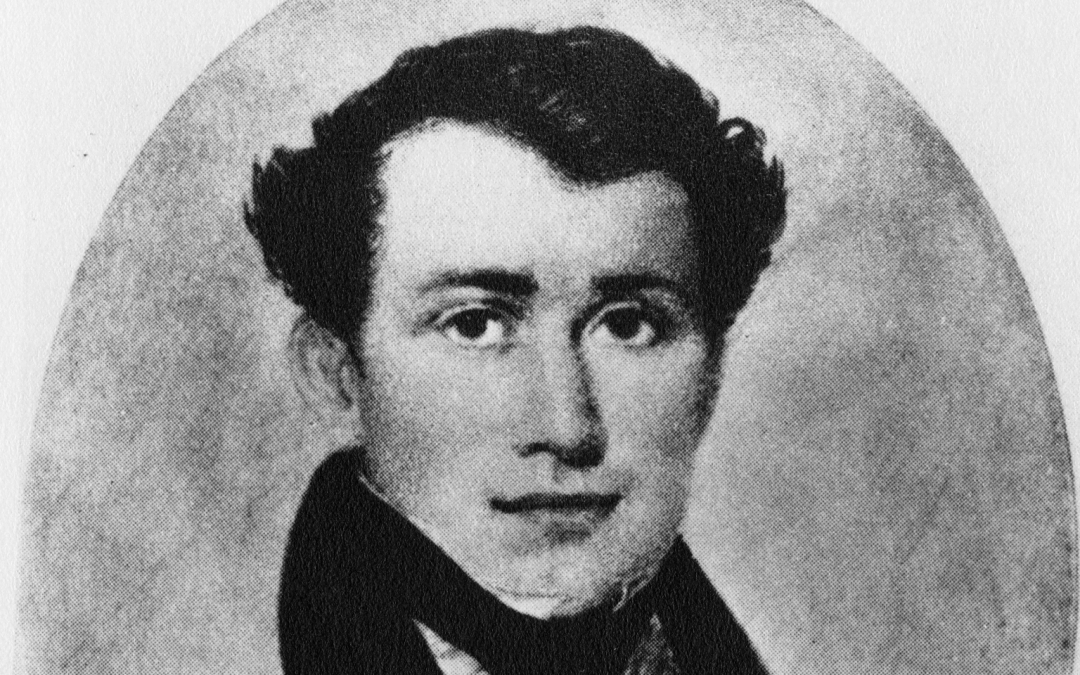

Photograph of a miniature of George W. Glover, n.d., P00782 © The Mary Baker Eddy Collection

The life of George Washington Glover (1811-1844)—Mary Baker Eddy’s first husband—is difficult to document; only three letters written by him are known to exist. One such letter is in our collection. Glover wrote it from Charleston, South Carolina, to his father John Glover (1773-1853) in Concord, New Hampshire, on July 30, 1839. This letter offers an insight into his daily life and captures the mood of Charleston in the months after the devastating fire of late April 1838, which according to accounts at the time destroyed a quarter of the city.

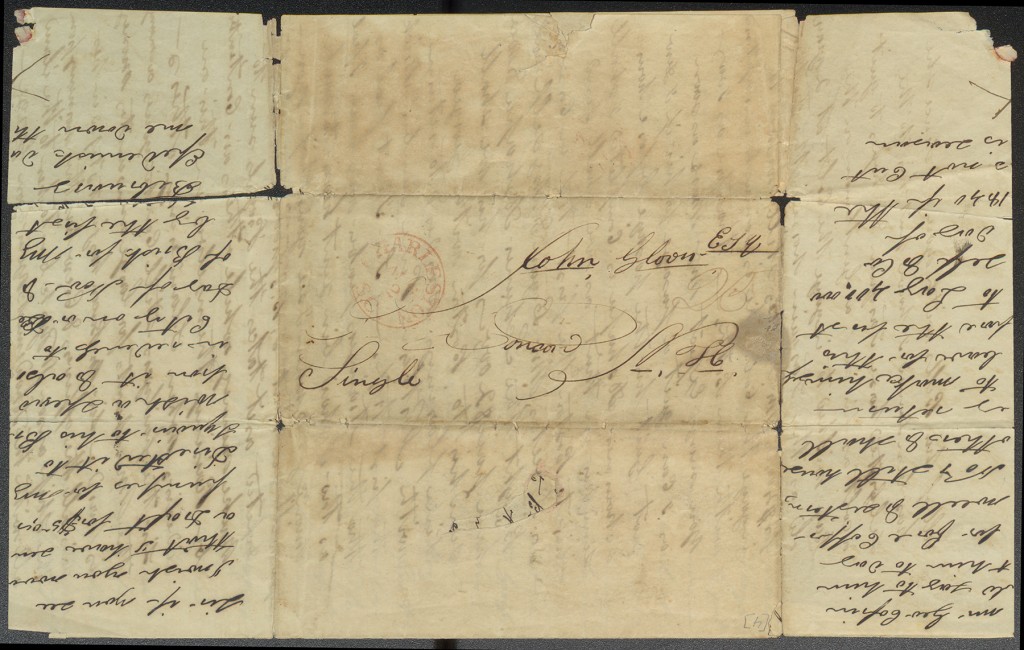

George W. Glover’s letter to his father, John Glover. This page shows the address and postmark. Library collections, Subject File 118

George W. Glover’s letter to his father, John Glover. This page shows the address and postmark. Library collections, Subject File 118

Glover’s first documented arrival in Charleston was on or about May 14, 1838.1 He possessed experience in several aspects of the building trade, having worked as a mason, carpenter, and builder. He arrived in Charleston two weeks after the fire and two weeks before the South Carolina General Assembly passed legislation to rebuild the area it had destroyed.2 His letter suggests he was able to capitalize on the publicly financed building boom, for he told his father about two properties he had under construction: “two young widows have [first] refusal of them two houses as soon as I complete at eight & twelve hundred a year.” It also seems he had other building projects planned for later that year, as he was preparing to “to lay four hundred thousand bricks for myself & company by the first day of February 1840.”

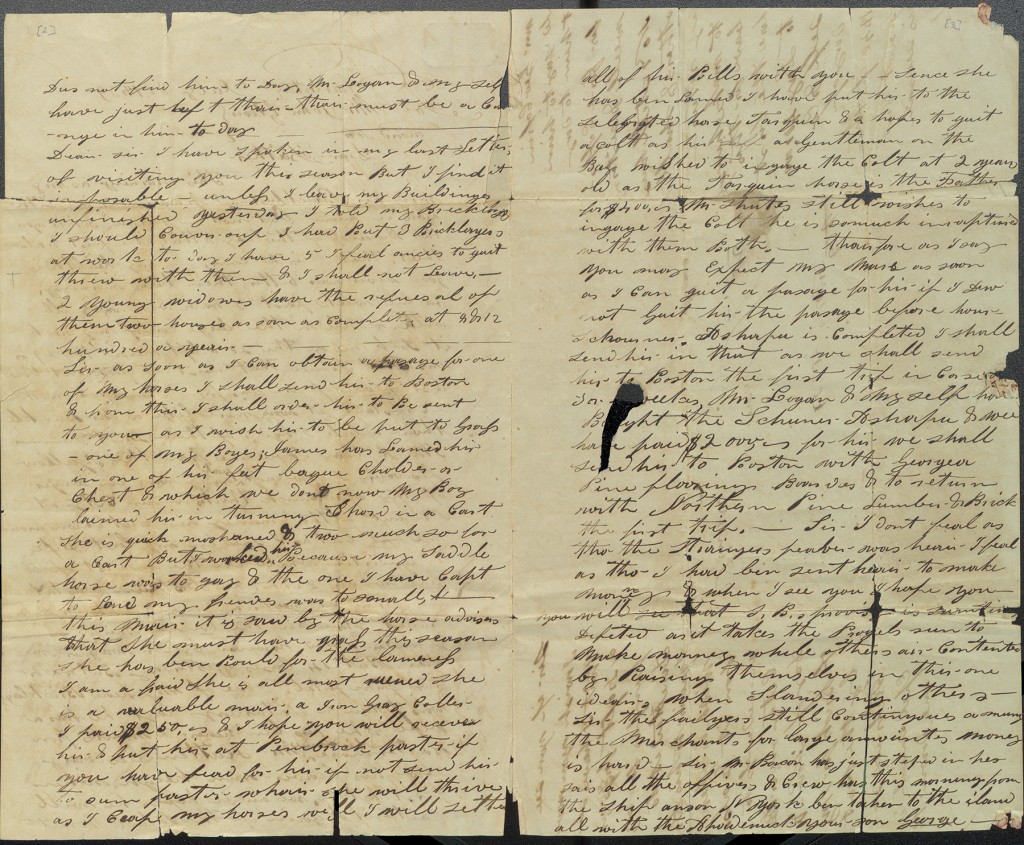

Another page from George Glover’s letter. Library collections, Subject File 118

Another page from George Glover’s letter. Library collections, Subject File 118

Perhaps believing he was on a kind of providential mission, Glover wrote to his father,“Sir I don’t feel as though the strangers fever [i.e., yellow fever] was here I feel as though I had been sent here to make money.” Armed with this belief, he began to diversify his business interests. Along with his business partner, George W. Logan, he purchased a schooner named Ashepoo for $2000, to transport building supplies between Charleston and Boston. The Ashepoo would run aground in November 1839, and the “hull, spars and standing rigging” would be auctioned off the following summer. We also learn that a “valuable mare” he had purchased was “put to the celebrated horse Tarquin.”3 Glover planned to return the horse to New Hampshire, where he hoped his mare’s colt would eventually derive at least $400 from stud fees. It’s not known whether or not this plan came to fruition.

Despite his efforts, none of Glover’s business ventures yielded any long term gains, while several ended in lawsuits brought either by him or against him. In January 1843, nearly 11 months before he married Mary Baker Eddy, he filed for bankruptcy in the United States District Court in Charleston. Then in February 1844, Glover and his young bride moved to Wilmington, North Carolina. There, tragically, “strangers fever” claimed his life on June 24, 1844, leaving his penniless and pregnant widow with no option but to return to her parents’ home in Sanbornton Bridge, New Hampshire. This marked the beginning of decades of personal challenges for Eddy, which she later referred to as “those lucid and enduring lessons of Love.”4 These lessons eventually led to her discovery of Christian Science in 1866.

[Note: Quotations from Glover’s original letter have been transcribed and the spelling corrected.]

- According to the May 14, 1838 edition of the Southern Patriot a Mrs. S. Glover (along with George Washington Glover) arrived from Boston aboard the brig Mohawk. She may have been the wife of George’s younger brother, Sullivan Glover (1813-1838) who possibly arrived in Charleston as early as June 1835. Sullivan and his wife Emily S. (Dame) Glover (c.1814-1838) would both die of yellow fever in Charleston within a few weeks of each other in the fall of 1838.

- On June 1, 1838, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified “An Act For Rebuilding the City of Charleston.” This legislation would see the state issue loans for the building of new stone and brick buildings.

- An advertisement in the June 12, 1839, Charleston Courier lists the lineage of Tarquin the “handsome and thorough bred horse,” as well as the stud fees, which were “$30 payable in advance, and $1 to the Groom.”

- Mary Baker Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection (Boston: 1892), 21.