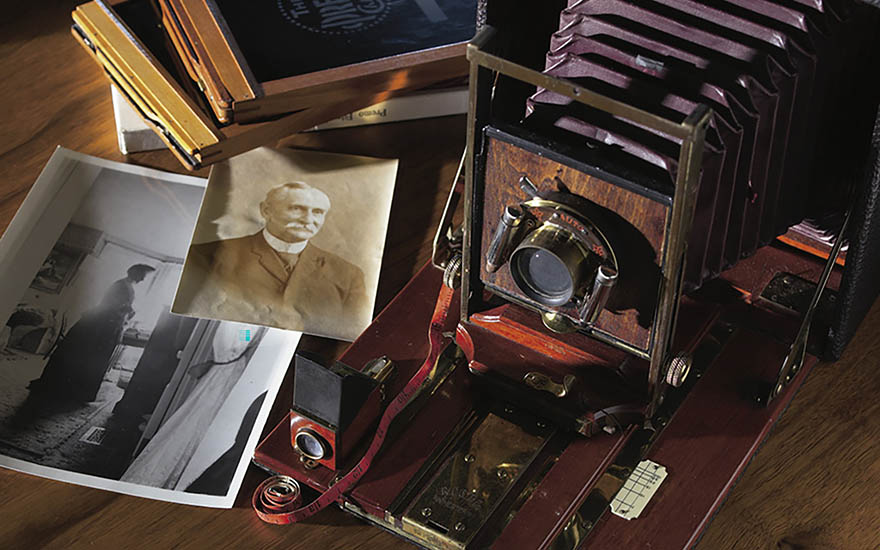

Calvin Frye’s camera

Pony Premo No. 6 camera owned by Calvin Frye.1984.37.407 A. Sold from 1903 to 1906, it was considered to be of higher quality and more versatile than the previous “Premos.”

Our collections include reminiscences from a number of people who served on Mary Baker Eddy’s staffs, in both her Concord, New Hampshire, and Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts homes. These often include descriptions of Eddy’s daily activities. As we read these accounts today, we might well wish we could go beyond imagining what the activities they describe were like, and actually see them.

And in a sense, we can. Because among the thousands of historic photographs in the Library’s collection many—some posed and some candid—depict daily life in these locations. As a matter of fact, we have these photos today largely because several staff members enjoyed photography as a hobby.

Eddy sometimes used optical terminology to illustrate her religious teachings. For example, she referred to the forerunner of photography, the camera obscura, in a letter to Christian Science churches in Chicago: “What is gratitude but a powerful camera obscura, a thing focusing light where love, memory, and all within the human heart is present to manifest light.”1

Photography became practical during the nineteenth century, after French doctor Joseph Nicéphore Niépcee (1765–1833) produced what is considered to be the first photograph in 1826. By 1835 he and Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851) had developed a technology that enabled the production of photographs known as daguerreotypes. One disadvantage of these images was that they could not be duplicated—each was unique. That problem was overcome by Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877), who developed a process called “calotype,” enabling the duplication of photographs. Improvements continued as the years went by, and by the time members of Eddy’s staff was enjoying picture-taking, photographic technology had developed to the point where cameras had hit the mass market.

Eddy’s employees used some of those cameras. One of them—a Kodak “Pony Premo No. 6”—is our object for this month. It belonged to Eddy’s secretary Calvin Frye and is a part of the Library’s Artifact Collection. The “Premo” camera line was developed by the Rochester Optical Company, which was taken over in 1903 by the Kodak Company.

While the collection contains photographs by various members of Eddy’s, Frye’s photos are particularly notable. He maintained a lively interest in technology throughout his life. So it was only natural that he’d be enamored by a technology that enabled people to permanently record visual images of events.

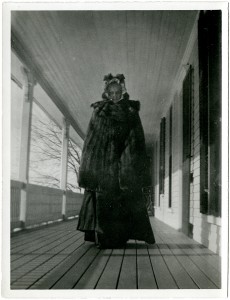

Mary Baker Eddy walks on one of the verandas of her Pleasant View home, undated. P00029.

Frye took quite a few candid photos of Eddy—she seems to have been one of his favorite subjects! And one of these these photos shows her walking on one of the Pleasant View verandas, dressed for cold weather. This may be somewhat similar to how she looked when artist James Gilman saw her on the veranda in December 1892. He described it in a letter to a friend:

I was sketching some details of the house from the rear, at the lower end of the grounds, some sixty rods away from it, when a dark figure came out upon the upper verandah [sic] (there are three of them the full length of the house…) and began to walk the length of the verandah and back. I was there sketching some fifteen minutes or more and the black figure walked vigorously back and forth the length of the piazza and return, constantly.2

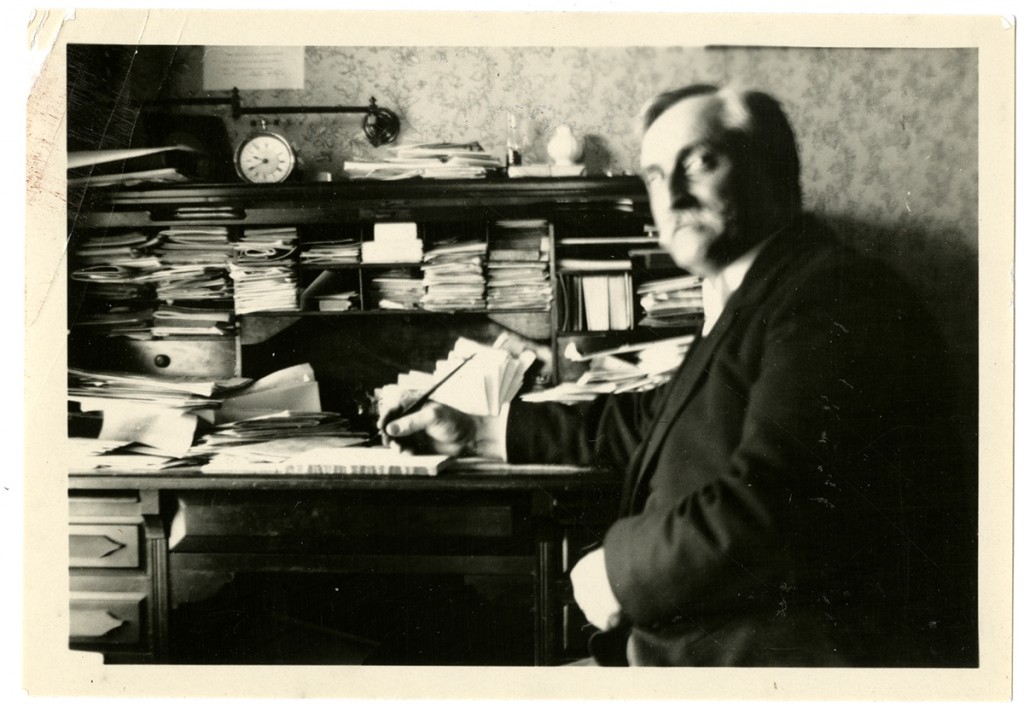

Today it’s common for smartphone owners to take “selfies.” And Frye may have enjoyed taking them, too—we have several possible examples in the collection. To take them, a person would mount a camera on a tripod and stand, or sit, holding a bulb connected by a cord to the camera’s shutter. When they were ready, a squeeze of the bulb would capture an image of the person.

When one compares photos taken in the nineteenth century to those of today, one difference is striking—the general absence of smiles. There have been various speculations as to why this is so. But the consensus today among scholars is that Victorians thought that smiling in photos would make them look foolish and frivolous. As Eddy’s contemporary and critic Mark Twain wrote, “A photograph is a most important document, and there is nothing more damning to go down to posterity than a silly, foolish smile caught and fixed forever.”3

Possible self portrait taken by Calvin Frye, undated (P00729). Courtesy of The Mary Baker Eddy Collection

Some of the photos that members of Eddy’s staff took do not show smiles. Others do. But whatever the demeanor of her dedicated workers, these pictorial records have come down to us as valuable visual images of what daily life was like as she and her staff enjoyed recreation, in addition to their labors in establishing the cause of Christian Science.

- Mary Baker Eddy, The First Church of Christ, Scientist and Miscellany (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 164.

- Painting a Poem: Mary Baker Eddy and James F. Gilman Illustrate Christ and Christmas (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors, 1998), 18, 19.

- Mark Twain and the Happy Island (Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co., 1913), 34.