Did Mary Baker Eddy say it? “Grandmother and the big black dog”

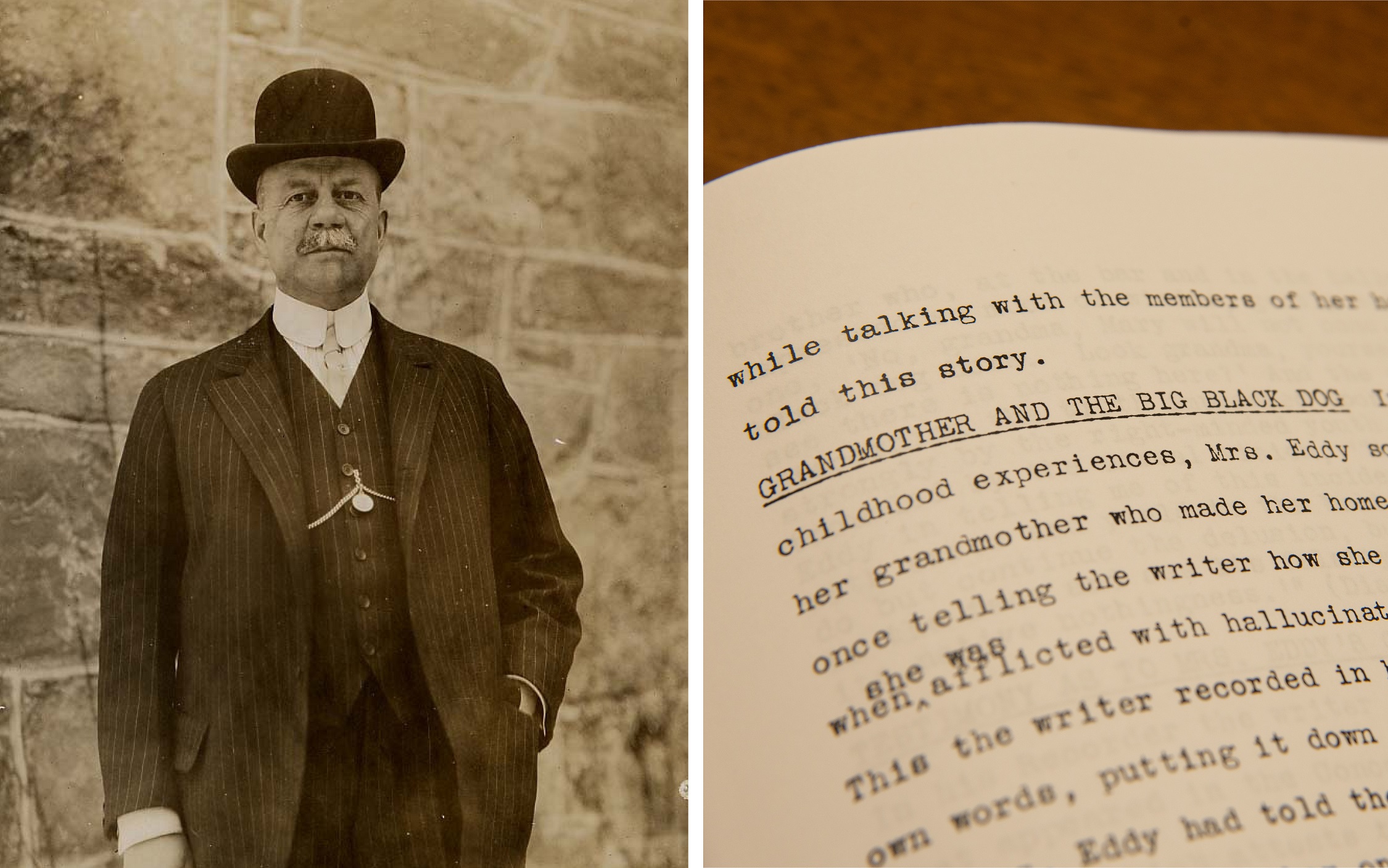

Irving C. Tomlinson, n.d. P01727. Photo by American Press Association.

Recently we were asked about the authenticity of an experience attributed to Mary Baker Eddy that mentions sight, hearing…and a dog!

The inquirer was likely thinking of the following account from the 1932 reminiscence of Irving C. Tomlinson (1860–1944). He worked on Eddy’s staff for a number of years, attended her last class in 1898, and was one of the first Christian Science lecturers.

Here is what Tomlinson recollected:

GRANDMOTHER AND THE BIG BLACK DOG In speaking of her childhood experiences, Mrs. Eddy sometimes referred to her grandmother who made her home with the Baker family, once telling the writer how she comforted her grandmother when she was afflicted with hallucinations about a big black dog. This the writer recorded in his diary at the time in his own words, putting it down as nearly as possible in the way Mrs. Eddy had told the story herself: “The aged grandmother on the paternal side made her home in the Baker homestead. It was little Mary’s joy to run errands for and to wait upon her dear grandma. In whatever way she could be of help she gladly rendered the service. At the time of which we write, the elderly lady was an invalid and occupied the front room on the first floor of the New England farmhouse. She was possessed with the strange delusion that every afternoon at about four o’clock a big black dog came into her room, ran under the bed, around the table, and over the sofa, very much to her annoyance. Every afternoon she was wont to call out, ‘Mary, Mary, Grandma wants you.’ When the obedient child had quickly answered the call, she would say, ‘Mary, please drive out the big black dog.’ Happy to gratify her beloved grandparent, little Mary would pretend to see the big black dog and would then shoo him out of the door. Grandma was satisfied and rested free from any trouble from the four-footed beast until the next afternoon, when Mary was again called to eject the fancied intruder. This continued until it attracted the attention of Mary’s brother Albert, and he said to her, ‘Mary, the next time grandma asks you to drive out the black dog, don’t you do it. There is no dog there, and she must get rid of her wrong notion.’ But the next afternoon, when the call came for help, the desire to bring comfort for the dear one in distress overcame her wish to obey the brother she loved, and going out of the doors to avoid her brother, she was about to enter the grandmother’s room by another door. As she was entering she saw her brother standing at the bedside of the invalid and heard her say, ‘Where is Mary? I want Mary to drive out the big black dog.’ Then the brother who, at the bar and in the halls of legislature expressed so much wisdom, gently said to the enfeebled one, ‘No, grandma, Mary will not come. There is no black dog here. Look grandma, yourself, do you not see there is nothing here?’ And the dear one looked, and discerning the truth impressed upon her so clearly and strongly by the right-minded youth, was never again troubled by the unreal vision, ‘Thus it is,’ said Mrs. Eddy in telling me of this incident, ‘when we agree with error and yield to the belief of its reality, we do but continue the delusion, but when we look it full in the face and see its falsity, then it vanishes into its native nothingness.’”1