Elizabeth Earl Jones, passport photograph, c. 1920. Courtesy of the

National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Washington D.C.

Elizabeth Earl Jones (1879–1963) is known in particular for her early efforts to defend the rights of Christian Scientists to practice their faith. She was a Christian Science practitioner and teacher who spent the majority of her life dedicated to healing, and even played the role of citizen detective and compiler. She was skilled in gathering historical information relating to the lives of early Christian Scientists. And she strongly believed this work played just as much a part in furthering the mission of Christian Science as did her own healing practice.

Born in Hendersonville, North Carolina, Jones suffered ill health in her early years. When she was still very young, her family moved to the nearby city of Asheville, where the climate was rumored to promote well-being and health. Apparently more than a change in location was needed, however—for by the time she was seventeen Jones was considered a semi-invalid. Doctors advised her father to withdraw her from school and encouraged outdoor exercise. Sophie B. Hazzard, a widowed friend of the family, invited Jones to stay with her during the winters on her South Carolina plantation. It was there she met friends of Hazzard who described the healing work of Christian Scientists in their home city of Charleston.

Hazzard encouraged Jones to write to Sue Harper Mims, a Christian Science practitioner in Atlanta, for help. Mims healed Jones through prayer, and soon both Jones and Hazzard began studying Mary Baker Eddy’s book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures. Three months later Jones wrote to Eddy and asked if Eddy could teach her Christian Science. Eddy responded that she had retired, but she recommended that Jones write to Mims for further instruction, which she did.1 More than a just a teacher, Mims became like a mother to her.

After her introduction to Christian Science, Jones dedicated much of her adult life to furthering its impact in North Carolina. She became a member of The Mother Church in 1899 and was also a charter member of First Church of Christ, Scientist, Asheville, where she served as First Reader from 1902 to 1905. She also worked as the assistant to Mary Hatch Harrison, the state’s Christian Science Committee on Publication (a position charged with correcting false reports about Eddy and Christian Science). Jones assisted Harrison for three years and then continued the work by herself until 1908. She recalled that even before then, when there was yet no Committee for either North Carolina or South Carolina, she had responded to newspaper attacks and “paid personal visits to clergymen and editors in her hometown….”2

Jones’s faith was tested in 1903, when legislation threatened to limit the protections of Christian Science practitioners. In response to charges of manslaughter,3 the state legislature introduced a bill stipulating that anyone practicing “suggestive therapeutics” would need to pass an examination before the medical board of the state.4 The bill was recalled and referred, and a hearing was scheduled before the joint Committee on Health of the House and the Senate.5 Jones relates that after the initial arguments, and testimonies from Christian Scientists, their lawyers proposed an amendment that granted an exception to the “treatment of the sick or suffering by mental or spiritual means without the use of any drugs or other material means.”6

Jones’s letter to Eddy, celebrating the amendment’s inclusion, was reprinted in The Christian Science Journal, along with a newspaper clipping from the News and Observer.7

Another significant chapter in Jones’s life involved the time she spent in England, from 1916 to 1920. After the United States entered World War I, she volunteered with the American Ladies’ Red Cross Aid Committee. Two letters, describing her experiences there are located in the North Carolina State Archives. The first gives us a detailed description of her work:

I was in England when America came into the war, and therefore I offered my services as a volunteer worker in ‘Eagle Hut,’8 and also as a volunteer worker in the ‘American Ladies’ Red Cross Aid Committee.’ This Aid Committee was formed of American women in the whole of England, and we co-operated with the American and British Red Cross. Our object was to do for our American wounded in the British Hospitals, what their own people at home would have done if they had been with them. We kept a record of every American who was in any hospital in the whole of England – and we visited them 2 or 3 times a week, lent them money, took them papers from home – and anything on earth they wanted from our big store rooms at 154 New Bond St. London. We also entertained them regularly as soon as they were well enough to get out and see things….We had a large house – 4 stories, on New Bond St. as our headquarters, – and we had a meeting once a week to report and to hear from one another and to perfect our work. I was a hospital visitor. Later…I was assigned to the United States Naval Hospital at ‘Allford House’ Park Lane, London….9

The second letter describes Jones’s sense of peace during an air raid and the Fourth of July celebrations overseas:

…we are not frightened and not downhearted, although they dropped leaflets saying they were coming again. In this house we knew nothing of it until it was right upon us. We went into the cellar and declared the truth out loud. They passed right over our heads but the nearest explosion was some way off, although it sounded as if each bomb was coming right through our roof. The noise is awful – it took me all day to get over it, and I was not frightened, either.…The 4th of July was wonderful….The Lord Chief Justice of England (Lord Reading) whom I met last weekend at Mrs. Guest’s country home – said he got the Monitor regularly and he thought it a most excellent paper….10

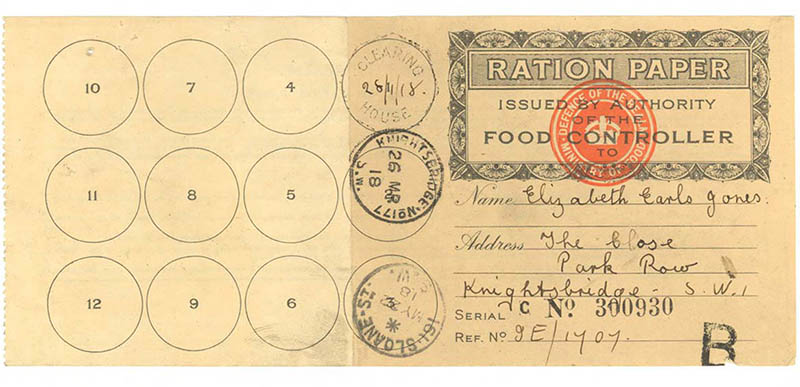

Elizabeth Earl Jones’s Ration Card, 1918, Courtesy of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources

In the late 1930s Jones wrote her memoirs, which included her investigations into Eddy’s life in the South during the early 1840s. Utilizing detective skills to try to recreate this era, she diligently asked locals and city officials for information and traveled to the locations where Eddy (then Mrs. Mary Glover) may have lived. Our collections include Jones’s sketches, drawings, letters, and newspaper clippings, which continue to help us understand this period of Eddy’s life.

While accomplishing much as a researcher and aid worker, the focus of Jones’s life was her work as a Christian Science healer. She began her practice in the early 1900s and became a teacher of Christian Science in 1940. She continued her healing and teaching work until her death in 1963.

Jones is buried at Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, North Carolina—the same resting place as famous authors O’Henry (William Sydney Porter) and Thomas Wolfe.

- Elizabeth Earl Jones, Mrs. Eddy in North Carolina and Memoirs, 146.

- Ibid., 96.

- Mary Hatch Harrison was found “not guilty” in 1901 after a patient of hers had passed on; there was insufficient evidence to prove her guilty of neglect.

- Ibid., 189.

- Ibid., 156.

- Ibid., 166.

- See Mary Baker Eddy, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany, 326-336.

- Jones explains that the “Eagle Hut” on “The Strand” was one of the most celebrated “Y.M.C.A.” huts abroad during the war and the largest one in London.

- Jones to Colonel Fred Olds, 2 September 1921, Courtesy of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, accessed June 29, 2016, http://digital.ncdcr.gov/cdm/ref/collection/p15012coll10/id/3379

- Elizabeth Earl Jones to May, Emmie, and Cammie Jones, 7 July 1917, Courtesy of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, accessed June 30, 2016, http://digital.ncdcr.gov/cdm/ref/collection/p15012coll10/id/3399