The founder of the Christian Science church, Mary Baker Eddy, was a Gilded Age celebrity. Her thoughts on issues, her comings and goings, even her carriage rides, were news. The papers reported on what she said and did, and often illustrated the articles with photographs and drawings. Eddy’s portrait was usually a part of these reports.

Her scrapbooks, which can be viewed in the Research Room of The Mary Baker Eddy Library, show us how widely these likenesses varied in their quality and accuracy. One infamous example is a supposed photograph of Eddy, used to illustrate the introduction to the highly critical McClure’s magazine series on her. This photograph, it turned out, was not of Eddy at all. (Author Robert Peel notes that the error “was a little too symbolic for editorial comfort in a journal that claimed to provide scrupulous documentation for its biographical bombshells.”)1

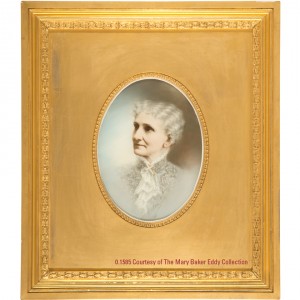

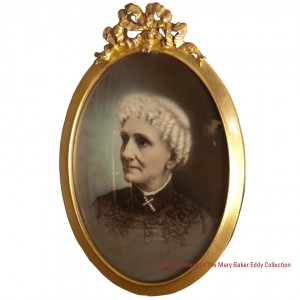

Mary Baker Eddy was not interested in self-promotion, but was aware of the need for good likenesses of her for use in publications. One of the best known and most widely published portraits of Eddy is by Alice C. Barbour (1879-1925), a Missouri artist who primarily painted on glass and ceramic. While Barbour did not paint her portrait from life, the work was created in Eddy’s last year, 1910, and received her approval just days before her passing that December.

The story begins several years earlier, when Barbour became interested in Christian Science and started to paint portraits of Eddy based on an 1886 portrait then placed in her Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896. Probably in about 1909 Barbour decided to use a more up-to-date portrait as her inspiration. An 1891 portrait of Eddy – showing her with white hair – became her model. Barbour found a market for her works among her fellow church members.2

This portrait of Mary Baker Eddy by Alice Barbour, based on an 1891 photograph taken by S.A. Bowers, was sent to Lillian Dickey in 1910. 0.1586.

By 1910, however, some had criticized her work, calling her portraits “unauthorized.” Barbour decided to consult Lillian Dickey, a good friend who was the wife of Adam Dickey, one of Eddy’s corresponding secretaries. In late May or early June, Barbour asked Mrs. Dickey if she might show her work to Eddy and receive her approval. Barbour hoped that perhaps in the future she could create a miniature portrait of Eddy “on a beautiful piece of ivory,” and she enclosed a sample of her work.3

Adam Dickey responded to Barbour. He felt it “one of the best reproductions of Mrs. Eddy that I have ever seen.” But he also noted: “Mrs. Eddy has never given anybody the right to make and put on the market a picture of her, except the one that is now being used in Science and Health; and while I do not think she would authorize you to make pictures of her, yet I do think she might allow it to be done without giving an official authorization, which would be all that you would require.” Dickey and Barbour continued to correspond throughout the summer, and both Dickey and Laura Sargent, a longtime member of Eddy’s Chestnut Hill household, gave Barbour valuable comments on capturing her appearance more accurately. By November 1910, Dickey reported that Eddy had seen the picture and was very pleased with it.4

Interestingly, at about this same time, Eddy was examining the portraits appearing in her books, and had decided that all should be removed.5 This might explain why Dickey was so explicit in his letter to Barbour: “You will understand that Mrs. Eddy does not give her consent to your making these pictures, but for the present her objection to it is withheld.”6

By the summer of 1911, this version of the Barbour portrait had been reproduced as a “photogravure” in sepia tones by The Christian Science Publishing Society and was available for sale. The Christian Science Sentinel announced the “admirable portraiture” as “an authentic and satisfactory picture of Mrs. Eddy.”7 (Color reproductions were not available until some decades later, in the 1940s.) Barbour continued to paint the portrait herself as well, in various sizes, on both porcelain and glass. These proved quite popular, especially with those who had known Mary Baker Eddy. In a letter to Barbour, Calvin Frye, Eddy’s longtime secretary, stated in his straightforward fashion: “Your portrait of Mrs. Eddy in water color on porcelain satisfies me; I am well pleased with it, and think you have made a faithful likeness of our beloved Leader.”8

Object of the Month readers: do you have a porcelain or glass painting by Alice Barbour? Would you like to tell us about your treasure? We’re interested in expanding our knowledge of her works, so please contact us here with your information (and your questions!)

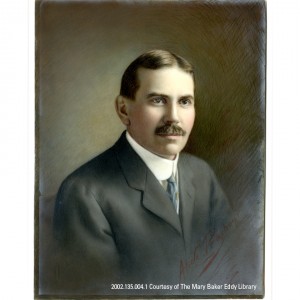

A portrait by Barbour, painted on glass, of Alfred Farlow, the first manager of the Christian Science church’s Committee on Publication. 2002.135.004.1.

- Robert Peel, Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Authority (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1977), 270.

- Daisy Alkire Logan, “History of the Barbour Picture of Mary Baker Eddy,” 2-3 (SF – Eddy, Mary Baker – Pictorial Works – Barbour, Alice). This document, dated 11 May 1955, appears to be based on Logan’s research into original documents then in the possession of the Barbour family. Unfortunately, the current whereabouts of these documents is not known, and so Logan’s research cannot be checked against the originals.

- Logan, “History,” 3-5.

- Logan, “History,” 5-10.

- Mary Baker Eddy to Allison V. Stewart, 26 October 1910, L09459; Eddy to Stewart, 10 November 1910, L07287.

- Logan, “History,” 10.

- Photogravure of Mrs. Eddy,” Christian Science Sentinel, July 8, 1911, http://sentinel.christianscience.com/shared/view/vvt73gcg4q?s=t.

- Logan, “History,” 27.