From the Collections: A forensic analysis of Calvin Frye’s diaries

Mary Baker Eddy’s life story has been told with varying degrees of accuracy and insight. Some of her antagonistic biographers claim that she was addicted to morphine, both before and after her discovery of Christian Science in 1866. Other biographers have stated that she was not an addict. Some Christian Scientists have gone further, maintaining that Mrs. Eddy never used morphine, even as the anesthetic for which it was often prescribed in her day.

Complicating this debate is the history of Calvin Frye’s diaries, which record several occasions of this use—including claims that the diaries fell prey to alterations, as well as forged entries.

We wanted to better understand what the diaries could tell us about these claims and counterclaims. In some ways, this controversy has been a distraction from Eddy’s larger record as discoverer, writer, teacher, healer, organizer, and leader. To learn more, the Library worked with a noted forensic examiner, who analyzed some of the documents. The steps taken to resolve this long-standing debate will benefit the Christian Science movement and all who are interested in the woman who founded it.

The following questions and answers explain this project and its conclusions.

QUESTION. Who was Frye?

ANSWER. Calvin A. Frye (1845–1917) worked for Mary Baker Eddy from 1882 until her passing in 1910. For most of those 28 years he served as her secretary, as well as a loyal confidant. He was a close associate and member of the household staffs that revolved around Eddy—first in Boston, then in Concord, New Hampshire, and finally in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. He was involved with, and aware of, the daily activities of as many as 25 household employees.

Q. What are the “Frye diaries”?

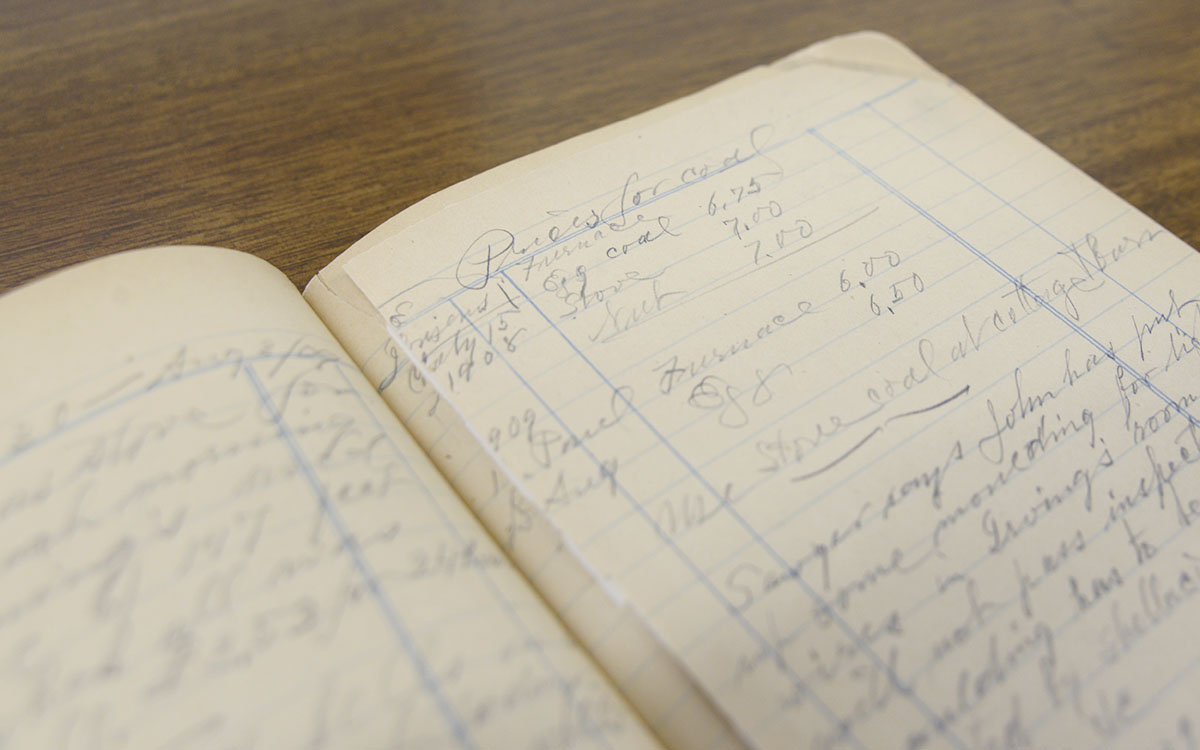

A. From 1865 to 1917, Frye kept daily records of events. He recorded financial transactions, accounting, general observations, and inspirational insights. Some are contained in small day books; others in more substantial hardcovers. Most were written in pencil, although some are in ink. Many include Frye’s short notations in Pitman shorthand. In a number of ways, the diaries more closely resemble dated notebooks than detailed records. Some were reused and include entries from different years.

Q. Why are the Frye diaries important?

A. They record daily life in close proximity to Eddy, as she and her followers established the Christian Science movement.

Q. Why is there controversy surrounding these diaries?

A. Among the thousands of notations in these books, Frye included entries about Eddy’s occasional illnesses and the prayerful help she requested from Christian Scientists around her. This Christian Science treatment was a form of prayer applied to the cure of physical ailments and other life problems. Christian Scientists continue to employ this method today.

Between 1903 and 1910, Frye’s diaries record Eddy’s bouts with renal calculi, or kidney stones. On several occasions he recorded that Eddy or her staff summoned a doctor to inject morphine as an anesthetic, to relieve extreme pain associated with this illness. On other occasions a doctor was called as a precaution but does not appear to have administered morphine. The diaries include records of payment for these services.

Q. Why would Eddy’s use of morphine as an anesthetic be controversial?

A. By the last decade of her life, Eddy had become a public figure. Among other things the press was interested in the state of her health. Since she promoted Christian Science as a system of healing through prayer, her own reliance on its teachings was scrutinized. Some newspapers reported that she took drugs for various ailments; was under the regular care of a physician; was dying of cancer; and was addicted to morphine. None of this was true. But the few Christian Scientists who knew about Eddy’s use of morphine as an anesthetic may have believed that public knowledge of it would result in attempts to discredit her—as indeed it did.

Q. What happened to the diaries after Eddy’s passing?

A. Frye continued to keep diaries after Eddy died on December 3, 1910. At the time of Frye’s death in 1917, church official John Dittemore took possession of many of these diaries. Perhaps he was fearful that they contained damaging information on Eddy. It appears that around that time he, or someone else, cut out some—but not all—pages that contained references to kidney stones and morphine injections. Other diaries were in the custody of Frye’s nephew, Oscar Frye.

Q. Who was Dittemore?

A. John V. Dittemore (1876–1937) was a member of the Christian Science Board of Directors, beginning in 1909. He was removed from office in 1919. This coincided with a period of litigation between The First Church of Christ, Scientist (The Mother Church) and The Christian Science Publishing Society. Dittemore’s removal from office led to his alienation from Christian Science. For a time he was an ally of Annie C. Bill (1861–1936), who claimed to be Eddy’s successor. She attempted to launch an organization in competition with The Mother Church. Bill’s magazine, The Christian Science Watchman, claimed that Eddy had medical treatment, probably based on information supplied by Dittemore.1

Dittemore broadly misconstrued what appears to have been the limited number of analgesic morphine injections Eddy received between 1903 and 1910. He reinterpreted her teachings and finally, by the late 1920s, attempted to discredit her. Along these lines he supplied excerpts from Frye’s diaries to Edwin F. Dakin, whose critical (and widely read) biography Mrs. Eddy: The Biography of a Virginal Mind was published in 1930.

Q. How did Dakin make use of the excerpts Dittemore furnished?

A. He used them as a part of his mainly fictional portrayal of Eddy’s life, characterizing her as a fraud, hysteric, and megalomaniac, as well as a morphine addict. Dakin’s distorted picture of Eddy continues to influence scholarship and public opinion about her, as well as Christian Science.

Q. Did Dittemore himself co-author a biography of Eddy?

A. Yes. He was credited with Ernest Sutherland Bates as author of Mary Baker Eddy: The Truth and the Tradition. This unfavorable biography, published in 1932, also quoted the Frye diaries.

Q. How did the Christian Science church acquire the Frye diaries?

A. After the lawsuits that began in 1919 were resolved in favor of the Christian Science Board of Directors, Dittemore made his own settlement with them. He turned over some of the Frye diaries, but insisted on burning pages that he had cut out of them. But unknown to the Directors at that time, Dittemore had made photostatic copies of those pages. Over the years, more of Frye’s diaries came into the possession of The Mother Church from two sources: Dittemore2 and Frye’s family. Eventually well over 100 diaries—including photostats made by Dittemore of some of the pages that had been destroyed—were collected. Today they are housed in the archives of The Mary Baker Eddy Library. Since 2002 scans of the diaries have been available to the public, through the services of the Library’s Research Room.

Q. How did The Mother Church respond to accusations that Eddy was a drug addict or had frequently employed doctors during this period?

A. The Christian Science Board of Directors published a published a statement in the January 26, 1929, Christian Science Sentinel, defending Eddy while acknowledging that she had used an anesthetic in a few episodes of extreme pain, probably in response to claims in The Christian Science Watchman.3

Q. Did this resolve the issues surrounding morphine?

A. No. Questions about Eddy and morphine have continued to resurface over the decades. On the one hand, Eddy’s detractors picture her as a drug addict, or as a hypocrite who relied on medicine contrary to her own teachings. On the other hand, some Christian Scientists reject the evidence that she ever used morphine as an anesthetic, despite the 1929 statement from the Board of Directors, not to mention Eddy’s own words in her book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures:

If from an injury or from any cause, a Christian Scientist were seized with pain so violent that he could not treat himself mentally, — and the Scientists had failed to relieve him, — the sufferer could call a surgeon, who would give him a hypodermic injection, then, when the belief of pain was lulled, he could handle his own case mentally. Thus it is that we “prove all things; [and] hold fast that which is good.4

Q. Have more recent biographies of Eddy addressed this question?

A. Yes. In the final book of his three-volume trilogy, Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Authority, published in 1977, biographer Robert Peel offered a documented assessment of the morphine question for the first time.5 Subsequent biographers have also included accounts.

Q. Why did the Library conduct a forensic document analysis of the Frye diaries?

A. Dittemore tampered with the diaries, cutting out and photostating pages. Some have claimed that the photostats might have been altered and were not in Frye’s handwriting, and that erasures on those and other pages point to attempts to alter the diaries’ content. Apparently contradicting the Frye entries are the statements of several Christian Scientists who served in Eddy’s household.6 In order to find out if there was a basis for the claims of forgery or alteration, the Library employed a noted forensic document expert, Khody Detwiler. He examined ten diaries that refer to morphine injections and payments to physicians. He also examined photostated pages, as well as pages that show signs of erasure and overwriting. He performed this work March 8–12, 2021, at The Mary Baker Eddy Library in Boston. He submitted his report in May 2021.

Q. How was the work done?

A. Detwiler used a combination of high-resolution magnification and lighting techniques, including oblique (lighting from the side, raking along the surface of the paper), and transmitted (lighting through the paper), as well as short bursts of UV lighting and infrared lighting. He examined all of the Frye diaries with questioned entries, as well as samples of other documents in either Frye’s or Dittemore’s handwriting.

In analyzing the handwriting in the various documents, Detwiler compared the formation of letters (how they were made) and the execution of penmanship (its speed and flow). He also performed analyses of the paper stock, inks, and obliterations (erasures). Even in cases where obliterations are complete, an analyst may still be able to read what was written on underlying pages, depending on how much pressure was applied during the writing.

These examinations formed the basis for Detwiler’s conclusion. He utilized a scale ranging from “Identification” (confirming authentic authorship of the document in question) to “Elimination” (confirming inauthentic authorship of the document in question), with “Probable,” “Strong Probability,” and “No Conclusion” as intermediate rankings.

Q. What were Detwiler’s conclusions?

A. He found that Dittemore did not write any of the questioned entries in the ten submitted Frye diaries. He further found that Frye did write those entries. In other words, his findings were “Elimination” of Dittemore and “Identification” of Frye.

In examining the erasures, Detwiler found that some words could be reconstructed, but that most could not. This was due to the fragility of the paper. Further analysis could be undertaken; however, this would require removing pages from the diaries.

Q. In the light of this forensic analysis, what do we know now that we did not know before about the Frye diaries?

A. We now know that Frye wrote the entries in the diaries related to morphine injections. We also know that Dittemore did not write these entries. It may not be possible to determine who made all of the many erasures, or to determine all of the words that were erased.

Q. Do the Frye diaries show that Eddy was addicted to morphine?

A. No. It would be difficult to interpret the diaries’ entries on this subject as indicating either substance abuse or addiction. They do record the administration of the drug as an anesthetic in several cases of extreme pain.

There is more to learn from the Frye diaries and other historical documents available to the public at The Mary Baker Eddy Library. The diary entries confirm that Eddy herself did indeed depend on Christian Science for healing during large and small illnesses. She sometimes asked others for treatment through prayer, and they helped her. Health problems constitute a minor part of what is contained in dozens of diaries in our collections, and we invite readers to contact us for more information about Eddy, her households, and their daily activities.

Listen to Examining the evidence: forensic handwriting analysis at The Mary Baker Eddy Library, a Seekers and Scholars podcast episode featuring Khody Detwiler and two members of the Library staff.

- See “Christian Science Committees on Publication Regarding Mrs. Eddy’s Use of Drugs,” 15 November 1928, signed by “The Editors of The Christian Science Watchman,” stating that Eddy in her later years “on numerous occasions … employed doctors who administered drugs and anaesthetics.”

- The resolution of Dittemore v. Dickey did not include removal of Dittemore from the Board of Trustees of the Christian Science Benevolent Association or from his position as a Trustee under the Will of Mary Baker Eddy. In order to effect his resignation from these boards and recover historical materials, the Christian Science Board of Directors made a financial settlement with him in 1924.

- “A Statement by the Directors,” Christian Science Sentinel, 26 January 1929, 430; republished in The Christian Science Journal, March 1929, 669. Op.cit., “Christian Science Committees on Publication Regarding Mrs. Eddy’s Use of Drugs.”

- Mary Baker Eddy, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 464.

- Robert Peel, Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Authority (Boston: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1977), 236–241.

- For example, see Irving Tomlinson’s 1930 statement, “Mrs. Eddy’s Reliance on God,” found in his reminiscence files. However, the reminiscence of Adelaide Still corroborates the Frye diaries. A letter by William R. Rathvon is more tentative.