From the Collections: Mary Baker Eddy’s carriage rides

Mary Baker Eddy seated in a Victoria carriage, with Calvin Frye holding the reins, Concord, New Hampshire, 1895. James F. Gilman. P00086

As head of the Christian Science movement, Mary Baker Eddy was occupied with many tasks, which included writing, teaching, and overseeing the establishment and growth of The Church of Christ, Scientist. This left few opportunities for leisure. By 1892, however, she was able to set aside time each day for an activity that provided a vital reprieve from work—a simple ride in a carriage.

Eddy began taking these excursions in 1892, after moving to the home in Concord, New Hampshire, that she named Pleasant View. She and her staff came to know them as her “daily drive.” While Eddy would often travel alone, occasionally other people accompanied her. For example, in 1900 she invited two of her students, Camilla and Septimus Hanna, to ride with her around the fairgrounds at the Concord State Fair.1

John Salchow, who worked for Eddy in several capacities over nine years, later recalled some of the preparations for the drives and the routes that she took:

It was my duty and privilege to see Mrs. Eddy at least twice a day nearly every day throughout the nine years I worked for her. I was always at the porte cochere [carriage entrance] regularly at one o’clock to hold the horses when she entered her carriage and at two o’clock when she returned from her drive – this being her customary hour. Mr. [Calvin] Frye always escorted her to the carriage, the maid holding the door open and tucking her in. August Mann drove and Mr. Frye sat on the box. At her request Mr. Joseph Mann would have peanuts and candies put up in little bags which he would give to Mrs. Eddy to take with her to distribute to the children she passed on her drive. She rarely if ever stayed out more than an hour and occasionally was only gone a half hour, except for the time that Mr. [Frank] Bowman drove her in from Chestnut Hill to see the Extension to The Mother Church. On her drives in Concord, Mrs. Eddy usually took one of three routes – down Fruit and South Streets, through Warren and State Streets, and until the St. Paul school closed the road, out past the school.2

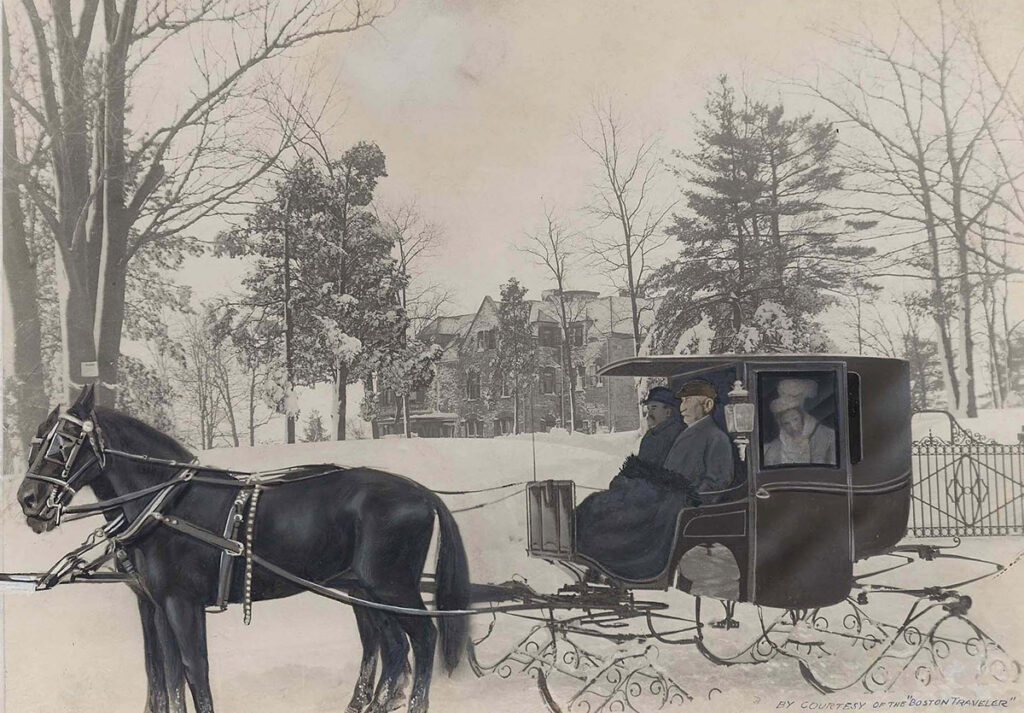

Eddy riding in a Brougham carriage, with sleigh runners for use in the snow, c. 1908–1910. P00164.

Salchow noted that “whenever there was the least bit of snow, enough to make the roads at all passable, we used to take the wheels off of her carriage and put on the runners [turning the carriage into a sleigh].” He went on to remember, “We had a couple of strings of silver bells for the horses and on a nice frosty day it made a pretty sight to see the sleigh and hear the jingle of the bells.”3

Eddy owned many carriages. They included a Brougham (which she had custom built to ensure her comfort on the drives); a Victoria carriage (named for Queen Victoria of England); an American station wagon; two American-built coaches; a two-seated buggy; a fringe-top surrey; and a double-runner sleigh.4

In addition to pleasure, the daily excursion was also what she once called “my time for communion with God.”5

And to that end, we find accounts of Eddy healing people she passed along the way. For example Julia Prescott, who served on the Pleasant View staff, recalled one such instance:

One day when Mrs. Eddy was taking her daily drive, she passed an old acquaintance on the street. He could scarcely walk with a cane, but her sense of God and the perfect man was so strong that he was healed. This was his statement in a letter following the incident, and which I heard our Leader read: “I have been very ill lately, and have suffered a great deal, but was entirely healed the day you passed me on the street. I am grateful to God.”6

By the late 1890s, Eddy was considered a celebrity, and the carriage rides constituted her most public-facing appearances. Crowds, which included Christian Scientists, would often line the streets in Concord (and later Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts) to glimpse her passing by. On July 1, 1904, Eddy wrote to the Christian Science Board of Directors, proposing a new By-Law for inclusion in the Manual of The Mother Church:

Neither a Christian Scientist, his student, or his patient, nor a member of the Mother Church — shall daily and continuously haunt Mrs. Eddy’s drive by meeting her once or more every day when she goes out – on penalty of being disciplined and dealt with justly by her church. Mrs. Eddy objects to said intrusion inasmuch as she desires one hour for herself. And she who for forty years has “borne the burden and heat of the day,” should be allowed this. The only exception to this By-Law is on public occasions, when she has the privilege of seeing others and of being seen.7

A few newspapers were taking notice of the crowds. This included the Boston Herald, which in July 1904 ran the headline “Faithful Annoy ‘Mother’ Eddy.”8

The By-Law was adopted as Article XXVI, Section 15, of the Manual’s 42nd edition (1904). For the 57th edition (1906), Eddy revised the text and changed the heading to “The Golden Rule.”9

During this time, some newspapers were publishing false claims that Eddy was ill or had died. One such claim in 1906 prompted her to write to the editor of the Boston Herald:

Another report that I am dead is widely circulated. I am in usual good health, and go out in my carriage every day.10

Minnie Scott, a maid at Pleasant View, noted that despite hostile attacks from the press, Eddy still went out on her ride:

… she was patient, courageous, and joyful. She never missed a day from her only recreation—her daily drive. [One] day when she returned, she no doubt felt the atmosphere of her home was intense ….11

False news reports were also circulating that staff member Pamelia J. Leonard was impersonating Eddy on the drives. Leonard and others were quick to deny such claims, and those refutations were published in a November 3, 1906, article in the Christian Science Sentinel titled “Baseless Charges Refuted.”12

On January 26, 1908, Eddy moved from New Hampshire to a large house that she had purchased in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, at 384 Beacon Street (now 400 Beacon Street). The purpose of the move was twofold: to allow her to be physically closer to the headquarters of the Christian Science movement in Boston, which would in turn make her better able to attend to her responsibilities as Pastor Emeritus of The Mother Church.

Some of the various carriages Eddy owned during her residence in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, c. 1908–1910. P05420.

The rumors that Eddy was ill or dead continued. Adam Dickey, one of her secretaries from 1908 until 1910, remembered a conversation he had with her about how the daily drives had now become more of a necessity:

She said to me, “Mr. Dickey, I want you to know that it does me good to go on this drive.” Instantly she felt my questioning thought and she replied, “I do not mean that the physical going for a drive does me good, but the enemy have made a law that it hurts me to go on this drive, and they are trying to enforce it, while I want you to take the opposite stand with God and know that every act I perform in His service does me good. I do not take this drive for recreation, but because I want to establish my dominion over mortal mind’s antagonistic beliefs.” 13

Eddy continued her daily drive until just two days before her passing on December 3, 1910. Salchow noted the following:

I remember the last day Mrs. Eddy went for her drive that while I did not notice anything very unusual, I was struck by the fact that her face did not show its habitual happy expression, though there was no outward evidence that she suffered from any special physical difficulty. When she returned, Mr. Frye and I escorted her to the rocking chair in the elevator and assisted her to her room. It was then that I noticed that she seemed to be contending with some strong belief. When I left her she was still seated in the rocker and I said good-bye as I always did. She had usually answered me with a simple “good-bye” or maybe a few pleasant words, but this time she did not. I got the impression that her thought was preoccupied. This was the last time I ever saw her. 14

Eddy’s daily carriage rides served as a vitally important activity during her later years, providing her with valuable solitude, recreation, and reflection. In fact, William Rathvon, her corresponding secretary from 1908 to 1910, remembered her as once having proclaimed, “I have uttered some of my best prayers in a carriage.”15

- Septimus J. Hanna, “Reminiscences of Mary Baker Eddy,” 1918, Reminiscence, 59–60.

- John Salchow, “Reminiscences of Mr. John G. Salchow,” 1932, Reminiscence, 25–26.

- “Reminiscences of Mr. John G. Salchow,” Reminiscence, 27.

- Photocopy of inventory book from Chestnut Hill, Newton, MA, 1951, Subject File, Eddy, Mary Baker (1821–1910): Residences – Chestnut Hill, MA – Inventory Book, 1951 – Access Copy, 182.

- Maurine Campbell, “The Story of the Busy Bees: An Account of Pioneer Experiences in Christian Science,” 1918, Reminiscence, 38.

- Prescott, untitled reminiscence, 1918, Reminiscence, 6.

- Eddy to Board of Directors, 1 July 1904, L00858.

- “Faithful Annoy ‘Mother’ Eddy,” Boston Herald, 11 July 1904.

- In the current (89th) edition, see Eddy, Manual of The Mother Church (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 48.

- Eddy to Editor of the Boston Herald, 19 October 1906, A10175.

- Minnie A. Scott, “Serving Mrs. Eddy – An Invaluable Experience,” We Knew Mary Baker Eddy, Expanded Edition, Volume II (Boston: The Christian Science Publishing Society, 2013), 377.

- See “Baseless Charges Refuted,” Christian Science Sentinel, 3 November 1906, 147–154.

- Adam H. Dickey, Memoirs of Mary Baker Eddy (Brookline, MA: Lillian Dickey, 1927), 73.

- Salchow, “Reminiscences of Mr. John G. Salchow,” Reminiscence, 121.

- William R. Rathvon, “Reminiscences of William R. Rathvon, C.S.B….,” 1941, Reminiscence, 66.