From the Collections: The Christian Science Monitor and Boston’s settlement houses

“Settlement Workers Are Busy,” The Christian Science Monitor, 11 October 1913, 8.

In October 1910, just before The Christian Science Monitor’s two-year anniversary, Editor Archibald McLellan addressed a gathering of Chicago businesspeople. He asserted that “the newspaper has become practically indispensable to the working out of human problems, and through it human thought has awakened to a growing sense of the unity and community of vital interests which exists among all members of the human family.”1

Founded during the heart of the Progressive Era, the Monitor brought its own vision of reform to a period in United States history known for projects and initiatives aimed at addressing large-scale social problems. Those included poor living and working conditions, juvenile delinquency, and the compromised health and welfare of underprivileged children.

As a new institution in Boston, the Monitor paid close attention to Progressive Era reform efforts in the city, featuring regular reports and columns on social work and social workers. Notable in this type of coverage were regular stories on the activities of settlement houses. These institutions looked to improve the lives and prospects of the urban poor, who were often non-English-speaking immigrants. In 1912 and 1913 alone, the paper printed well over 50 articles on settlement houses. Here we will explore what that coverage reveals about Boston’s social history and how the Monitor’s coverage served that “unity and community of vital interests” for the city.

In his 1958 book Commitment to Freedom: The Story of the Christian Science Monitor, Erwin Canham discussed the nature of the paper’s early relationship with its home city. The Monitor, he noted, “sought to be an effective local newspaper . . . having many columns of civic and community news every day.”2 This included a regular series called “Among the Settlements,” which reported on educational and other programs for immigrant groups. Another was on “Social Service Work.” Along with other articles from this period, these series provide a significant reservoir of information about the history and legacy of social services and educationally minded philanthropic institutions in Boston. They bring to life the various activities and opportunities that shaped the prospects of first- and second-generation immigrants in Progressive Era Boston. Moreover, they reflected core Monitor journalistic values. McLellan spelled out the paper’s objectives at the time of its founding:

It is intended that the Monitor shall contain, in addition to the usual news features of the best city papers, such special departments as will make it a home paper of the highest grade, – one which will appeal to good men and women everywhere who are interested in the betterment of all human conditions and the moral and spiritual advancement of the race.3

Boston experienced a massive demographic transformation during the Progressive Era, a period identified with the late nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth. The peak years for immigrants coming to Boston during this period were the 1910s, when they constituted “nearly 40 percent” of the population.4 Frances J. Kemp calculated in her article “Impressions of Boston 1880–1910” that, at this time, “almost two-thirds of the population consisted of the foreign-born and their offspring.”5 And she explained how the impact of this sudden surge of population stretched the city’s resources:

Problems resulting from the overcrowding involved sanitation, employment practices, imbalance of the sexes, and destitution of those who couldn’t cope with the shock of being transplanted. In their letters to the Old Country, some immigrants discouraged others from coming to Boston, so ill-prepared was the city to receive them.6

As a result philanthropists, together with social workers, responded by making Boston a pioneering city in the establishment of settlement houses. These forms of outreach aimed at supporting these new communities in their efforts to build new lives in a new world.

Settlement houses were often referred to as “college” or “university” settlements, because the educators who resided in them often came directly from institutions of higher learning. They sought to break down class differences through communal educational activities. Core to their purpose was a commitment to the progressive educational ideas and practices they brought to the settlement houses as spurring upward mobility on a variety of levels, reflecting “the belief that the educated elite could materially, socially, and morally impact the mass of immigrants moving to cities.”7 A 2020 report by the Alliance for Strong Families and Communities supports that assertion:

These houses served as gathering places for fostering relationships that would serve as the foundation for stronger, healthier communities. Middle- and working-class individuals lived side by side in fellowship. . . . Child care, education for children and adults, health care, and cultural and recreational activities were common.8

The settlement house reflected the emergence of sociology as an important field of academic study, and with it the advent of the professional social worker. “‘Social reconstructionism’ became a profession,” said Kemp, “and workers tried to merge ethical motives with scientific methods in order to improve American life.”9 According to Dr. Meg Streiff, this stood in contrast with “mid-nineteenth century social reformers [who] focused on moralism, and viewed poverty as the product of vice and moral failure.” She explains that “settlement workers viewed poverty largely as an environmental problem that they could help solve through settlement-sponsored activities and amenities.”10

The institution of the settlement house began in 1884 in London’s East End. It came to the US through individuals such as Robert A. Woods, who studied the British model during a six-month stay in England. Woods became a political leader in the settlement house movement in Boston and in the United States. He was educated at Amherst College and at the Andover Newton Theological School, both located in Massachusetts. He helped found Andover House (named after the Andover Newton seminary) in Boston’s South End neighborhood in 1891, as the first settlement house in the city and the fourth in the nation.11 Andover House would soon change its name to South End House, reflecting its commitment to the neighborhood—which, in fact, bordered the Monitor’s own publishing site. In recent decades the South End has become heavily gentrified. That stands in sharp contrast to the neighborhood in the early twentieth century, when, along with other downtown neighborhoods such as the North End and West End, it was among the more impoverished. Initially these communities were home mostly to Irish immigrants, before “new immigrants, particularly eastern European Jews and Italians, began to take the place of the Irish in downtown districts.”12

Photo of Robert A. Woods, c. 1912. Photographer unknown.

Source: The Christian Science Monitor.

In a piece titled “American Social Workers Take Courage,” the Monitor invoked Woods’s work and ideas as representative of the advances in social work in the US:

In the 1913 annual report of the South End house, the veteran social settlement worker of Boston, Robert A. Woods, dwells upon the satisfaction which he and other men and women of his calling find in the present state of American national politics.” Social problems that, twenty years ago in this country, were just emerging above the horizon of those pioneers from universities and colleges who, like himself, decided to study urban conditions at first hand, are now vital and divisive in the field of national politics….13

In another article, the Monitor explored the growth of the social work profession in Boston, and its manifestation in the settlement houses. About its coverage, it noted that “much publicity has been given the excellent service rendered by the settlements and neighborhood houses of Boston, but hitherto only brief mention has been made of the men and women who devote their energies entirely to this work ….” The article went on to cite that “there are today in Boston, including Roxbury, 125 men and women devoting themselves to social service in the various settlements and neighborhood houses,” and adding, “social service, as every one knows, is not a money-making profession ….”14

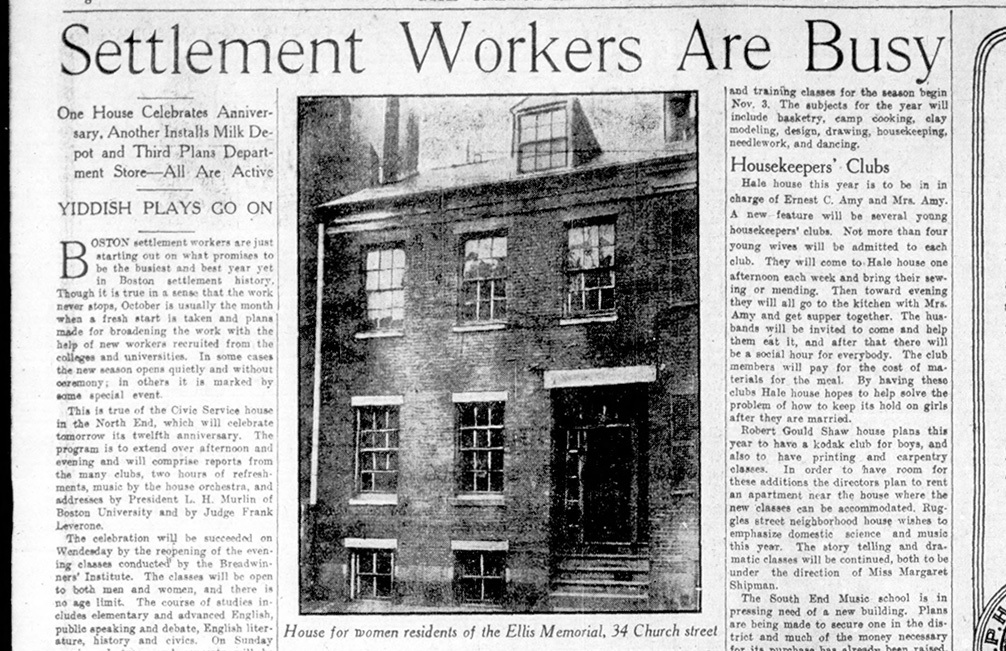

Indeed, the Monitor had “given much publicity” to the activities of settlement houses in Boston. There was coverage of Woods’s South End House and of other settlement institutions in that part of the city, including Hale House, established in 1895; Lincoln House (1895); Harriet Tubman House (1904); Ellis Memorial and Eldredge House (c. 1900); and the Children’s Art Centre (1918), as well as of settlement houses and social service agencies in other parts of the city. The nature of the coverage typically involved reporting on plans, activities, and accomplishments of various groups. For example, an article from October 11, 1913, titled “Settlement Workers Are Busy,” carried the subheading “One House Celebrates Anniversary, Another Installs Milk Depot and Third Plans Department Store – All Are Active.” And below that, in all capital letters: “YIDDISH PLAYS GO ON.”15 Information in the article reflected the Monitor’s style of reporting on settlement house activities, which was generally positive and supportive, while giving a rich and often detailed picture of the nature of the movement’s educational and cultural outreach:

Boston settlement workers are just starting out on what promises to be the busiest and best year yet in Boston settlement history. Though it is true in a sense that the work never stops, October is usually the month when a fresh start is taken and plans made for broadening the work with the help of new workers from colleges and universities….16

The article then went on to report on the twelfth anniversary of the “Civic Service house” in Boston’s North End, which was a hub for immigration, with a growing population of recent arrivals from Italy. It detailed plans for the anniversary celebration: “The program is to extend over afternoon and evening and will comprise reports from the many clubs, two hours of refreshments, music by the house orchestra, and addresses by President L. H. Murlin of Boston University and Judge Frank Leverone.” It then followed with an outline of post-celebration educational activities at the North End center, capturing the ethos of the settlement house mission to bridge the worlds of the immigrant and the established bastions of American higher education:

The celebration will be succeeded on Wednesday by the reopening of the evening classes conducted by the Breadwinners’ Institute. The classes will be open to both men and women, and there is no age limit. The course of studies includes elementary and advanced English, public speaking and debate, English literature, history and civics. On Sunday evenings lectures and concerts will be held under the auspices of the institute. The faculty will consist mostly of students from Harvard University and Emerson College of Oratory ….17

The Monitor also spotlighted the ingenuity and innovation of Boston’s tenement dwellers in finding solutions to the often-suffocating conditions in which they lived. One article titled “Picnics, Parks and Schools on Boston’s Roofs” noted:

So few Bostonians realize the extent to which roofs in the big cities are utilized, or what scope these utilitarian purposes are made to cover . . . .

Yet in the North and West ends where crowded narrow streets and small dark rooms combine to make the refuge of the roof doubly valuable to the tenement families, particularly on hot summer nights, these novel uses of house tops are to be found in extended variety….18

The article described the variety of uses roofs played as flower and vegetable gardens, parks, alternative sleeping areas, outdoor schoolrooms, and places to view fireworks on the Fourth of July (something Bostonians continue to enjoy today). The piece also portrayed boys taking woodworking at the North Bennet Street Industrial School, which afforded the opportunity for them to be caretakers of the roof at the local Social Service house in the North End neighborhood. “[They] are given a chance to repair it,” the article noted, “and thus learn the meaning of cooperation for the good of the neighborhood.”19 Of note, in 1885, the school’s librarian requested a copy of Mary Baker Eddy’s book Science and Health, which Eddy provided.

“Picnics, Parks and Schools on Boston’s Roofs,”

The Christian Science Monitor, 19 July 1913, 8.

While there has been much literature critiquing the settlement house as a “paternalistic” institution, other research into the movement suggests a more nuanced, and even reciprocal, relationship between the new arrivals and the residents who came to the settlements to teach and work with them. For example, it’s been noted that for South End House leader Robert A. Woods, the settlement house “became ‘common ground’ where representatives of all groups met and mingled together and where prejudices were discountenanced. As Woods expressed it, such intergroup contact encouraged a reciprocity of influence among the foreign-born and the native-born.”20

In keeping with Woods’s sentiment, Monitor reporting on activities in Boston settlements suggested an affirmation that the contributions of immigrant culture were important—typified in an October 11, 1913, piece in its coverage of the activities of Jewish immigrants:

Yiddish plays at the Elizabeth Peabody house theater are to be continued indefinitely every evening and Saturday afternoon. Various types of plays are to be tried and sometimes operettas. Special days will be chosen for the presentation of plays before the students from Harvard, Radcliffe, Wellesley and the Institute of Technology….21

“Jewish People’s Institute Does Helpful Things for New Comers,”

The Christian Science Monitor, 11 September 1912, 5.

Many of the settlement houses that the Monitor reported on continue to this day. For example, Woods’s South End House is now part of the United South End Settlements, a merger of various settlement houses in that neighborhood with origins in the Progressive Era.22 The North Bennet Street School has also developed an international reputation for training students in fine craftsmanship.

In a 1912 editorial titled “Urban Neighbors Unite,” the Monitor noted:

During the past decade, largely through the service of the South End house and its auxiliaries, a change has come over the depressing situation facing owners of property…. An improvement association has been formed, with officials and members representing all the various racial, religious and economic differences of citizens…. There is a note of hope now where gloom was fast settling down. The old ideal of neighborliness is being restored.23

Another editorial from 1912, titled “Transmission of Ideals,” signals why the Monitor devoted such consistent attention to the subject of settlement houses in Boston. In it, the paper opined on the achievements of the South End House in response to the institution’s twenty-year anniversary report on service to that neighborhood. It began with a sketch of the history of the settlement movement with its origins in England, “where Stanton Coit, Jane Addams and Robert A. Woods got the insight and training to initiate settlement work in New York, Chicago and Boston.”24 Later on the piece observed:

Twenty years of residence in a district, all the time studying it, with a view to its uplift, gives a man knowledge that educators, priests and preachers, lawmakers and police, who come and go, value. Thus the settlement becomes a civic center, a power-house, a social center.25

Moreover, Monitor interest in activities associated with Boston’s settlement movement extended beyond reporting and editorializing. A piece in the paper’s column on “Social Service News” reported that young women from the Saturday Evening Girls of the Library Club would have “a visit to the Christian Science Publishing Society, where the girls will inspect the workings of the various departments of The Christian Science Monitor.”26 Designed “to provide intellectual and social stimulation on Saturday evenings to poor, young Jewish and Italian working women and girls living in the North End of Boston,” the Saturday Evening Girls Clubs began at the North Bennet Street Industrial School in 1899.27 “Many of the Saturday Evening Girls went on to inspire and educate others through civic service, social service careers, teaching, the arts, and philanthropy,” observed Kate Larson in a 2001 article in The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy. “They became librarians, office and clerical workers, social workers, teachers, saleswomen, business owners, musicians, and artists.”28

The Boston settlement house was a testament to the ideals of Progressive Era reform efforts. Christian Science Monitor coverage of and interest in this work shines a generous light on its influence in shaping the lives of new (and old) Bostonians, women as well as men, during a time of mass immigration to the city—one that still resonates today.

For more discussion on this topic, listen to our Seekers and Scholars podcast episode “The Christian Science Monitor, social work, and Boston’s settlement houses.”

- Archibald McLellan, untitled address, n.d., 1, Subject File, McLellan, Archibald (d.1917) – Addresses by and Biographical Material.

- Erwin Canham, Commitment to Freedom: The Story of The Christian Science Monitor (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1958), 103.

- Archibald McLellan, “The Christian Science Monitor,” Christian Science Sentinel, 17 October 1908, 130.

- “Second Wave Immigration, 1880–1921,” Global Boston, n.d., https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/home/eras-of-migration/test-page-2/

- Frances J. Kemp, “Impressions of Boston: 1880–1910,” Quarterly News (Longyear Museum), Autumn 1981, 283. https://www.longyear.org/learn/research-archive/impressions-of-boston-1880-1910/

- Kemp, “Impressions of Boston,” 283.

- Russ Lopez, Boston’s South End: The Clash of Ideas in a Historic Neighborhood (Boston: Shawmut Peninsula Press, 2015), 49.

- Alliance for Strong Families and Communities website, “History of the Settlement House Movement,” 2020. https://www.alliance1.org/web/resources/center-engagement/history-settlement-house-movement.aspx

- Kemp, “Impressions of Boston,” 284.

- Meg Streiff, Boston’s settlement housing: social reform in an industrial city,” Doctoral dissertation, Louisiana State University, 2005, viii. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1217&context=gradschool_dissertations

- See Lopez, Boston’s South End, 48.

- James J. Connolly, The Triumph of Ethnic Progressivism: Urban Political Culture in Boston, 1900–1925 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1998), 17.

- “American Social Workers Take Courage,” The Christian Science Monitor, 12 March 1913, 28.

- “Hundred or More Regular Workers in City Social Service,” Monitor, 16 March 1912, 21.

- “Settlement Workers Are Busy,” Monitor, 11 October 1913, 8.

- “Settlement Workers Are Busy,” Monitor, 8.

- “Settlement Workers Are Busy,” Monitor, 8.

- “Picnics, Parks and Schools on Boston’s Roofs,” Monitor, 19 July 1913, 8.

- “Picnics, Parks and Schools on Boston’s Roofs,” Monitor, 8.

- George Cary White, “Social Settlements and Immigrant Neighbors, 1886–1914,” Social Service Review, March 1959, 59.

- “Settlement Workers Are Busy,” Monitor, 8.

- United South End Settlements (USES) website, accessed 1 May 2023. https://www.uses.org/about-us/mission/

- “Urban Neighbors Unite,” Monitor, 6 September 1912, 16.

- In 1886, Stanton Coit founded “the Neighborhood Guild, a settlement house in New York City, now known as University Settlement House” (see Jane Addams Papers Project, https://digital.janeaddams.ramapo.edu/items/show/24, Accessed August 21, 2023). In 1889, Jane Addams founded Hull-House in Chicago, often credited as the first settlement house in the United States (see Peter Gibbon, “Jane Addams: A Hero for Our Time—Remembering the Founder of Hull-House,” Humanities, Fall 2021, 42, no. 4, and The National Endowment for the Humanities: https://www.neh.gov/article/jane-addams-hero-our-time). As noted above, Robert A. Woods helped found Andover House, Boston’s first settlement house, in 1891, subsequently renamed South End House.

- “Transmission of Ideals,” Monitor, 21 March 1912, 16.

- “Social Service News,” Monitor, 4 November 1912, 5.

- Kate Clifford Larson, “The Saturday Evening Girls: A Progressive Era Library Club and the Intellectual Life of Working Class and Immigrant Girls in Turn-of-the-Century Boston,”The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, April 2001, 195.

- Larson, “The Saturday Evening Girls,” 198–199.