How did Eddy respond in times of national crisis?

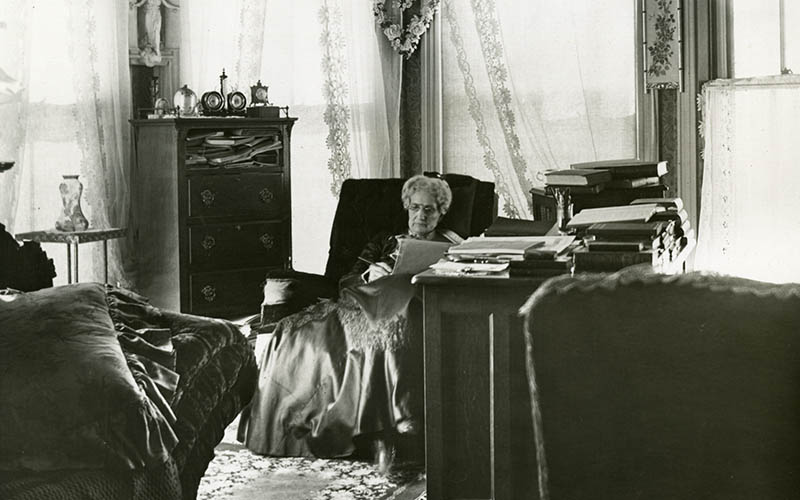

Mary Baker Eddy seated at her desk at Pleasant View, early 1900s. P00036. Calvin A. Frye.

Considering the events at the United States Capitol on January 6, we wondered what our archives could tell us. What example did the leader of the Christian Science movement set in such turbulent moments?

A number of national calamities arose during Mary Baker Eddy’s lifetime. One of particular significance was the 1901 assassination of William McKinley (1843–1901), the 25th American president.

On September 6, Leon Czolgosz shot McKinley at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. For almost ten days the president held to life. Initially many expected him to recover, and his death on September 14 brought grief and anger to the nation.

Eddy had been interested in McKinley, saving articles about his presidency in her scrapbooks, where she kept track of people and events she found significant.1 She had written to his wife, Ida S. McKinley, on March 30, 1898, during the time she was First Lady. The letter mentioned the growth of Eddy’s religion and legal attempts to limit its practice. “Notwithstanding this,” Eddy wrote, “I admonish Christian Scientists never to take the sword but always endeavor to overcome evil with good. And obeying this rule the prosperity of Christian Science is unexceptional, for the Principle [which governs it] is mighty in demolishing wrong and sustaining right.” She closed, “Accept my heartfelt hope that you are in health and the enjoyment of a peace that the world cannot disturb.”2

Aware of the assassination, Eddy wrote a letter of condolence and comfort to Ida McKinley. Dated the day of the President’s death, it began: “My soul reaches out to God for your support, consolation, and victory. Trust in Him whose love enfolds thee. ‘Thou wilt keep him in perfect peace, whose mind is stayed on Thee: because he trusteth in Thee.’ ‘Out of the depths have I cried unto Thee.’”3

A tribute to McKinley by Eddy quickly appeared in her church’s magazines. In the last paragraph, she wrote:

What cannot love and righteousness achieve for the race? All that can be accomplished, and more than history has yet recorded. All good that ever was written, taught, or wrought comes from God and human faith in the right. Through divine Love the right government is assimilated, the way pointed out, the process shortened, and the joy of acquiescence consummated. May God sanctify our nation’s sorrow in this wise….”4

Houses of worship had offered fervent prayers for the President’s recovery, as did many individuals. His lingering death had gripped the country. Sensitive to this malaise, Eddy responded with “The Power of Prayer,” an article that began by asking a question on the minds of many: “Why did Christians of every sect in the United States fail in their prayers to save the life of President McKinley?”5 Eddy’s 1875 book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures includes a chapter offering an extended treatment of prayer,6 and this article applied some of its ideas to Americans’ current crisis of faith.

Mary Baker Eddy’s response to this national emergency was both alert and pastoral. It expressed a thoughtfulness and depth that the editor of Harper’s Weekly remarked on:

All the preachers preached on President McKinley; all the editors wrote about him. There was a great deal to say, and most of it seems to have been said. Of course thousands of writers and speakers said about the same things, for they dealt with the same facts, and they were moved by the same feelings. Among others who have spoken was Mrs. Eddy, the mother of Christian Science. She issued two utterances which were read in her churches, one a letter of sympathy and advice to Mrs. McKinley. Both of these discourses are seemly and kind, but they are materially different from the writings of any one else. Reciting the praises of the dead President, Mrs. Eddy says: May his history waken a tone of truth that shall reverberate, renew euphony, emphasize humane power, and bear its banner into the vast forever. No one else said anything like that. Mother Eddy s style is a personal asset. Her sentences usually have the considerable literary merit of being unexpected. Her letter to Mrs. McKinley was short, sympathetic, religious, and very much to the point. Her position in the country as the head and chief spokesman of an important religious body is very curious and highly interesting.7

- “The diplomatic officials congregated at the British embassy …,” Concord Monitor, Scrapbook 6, SB006; “The Fight Against Mr. Quay,” The Outlook, Scrapbook 24, section 3, SB024.03; “Claims Descent from King David,” unknown journal, Scrapbook 25, section 2, SB025.02, The Mary Baker Eddy Collection.

- Mary Baker Eddy to Mrs. William P. McKinley, March 30, 1898, L09560.

- Mary Baker Eddy, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 290.

- Mary Baker Eddy, “True Greatness,” Christian Science Sentinel, September 26, 1901;The Christian Science Journal, October 1901; reprinted in The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany, 292.

- Eddy, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany, 292.

- See Mary Baker Eddy, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 1–17.

- E.S. Martin, “This Busy World,” Harper’s Weekly, 5 October 1901, 1011, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015030326337&view=1up&seq=11. Also quoted by Irving C. Tomlinson in “Notes,” n.d., A11788.