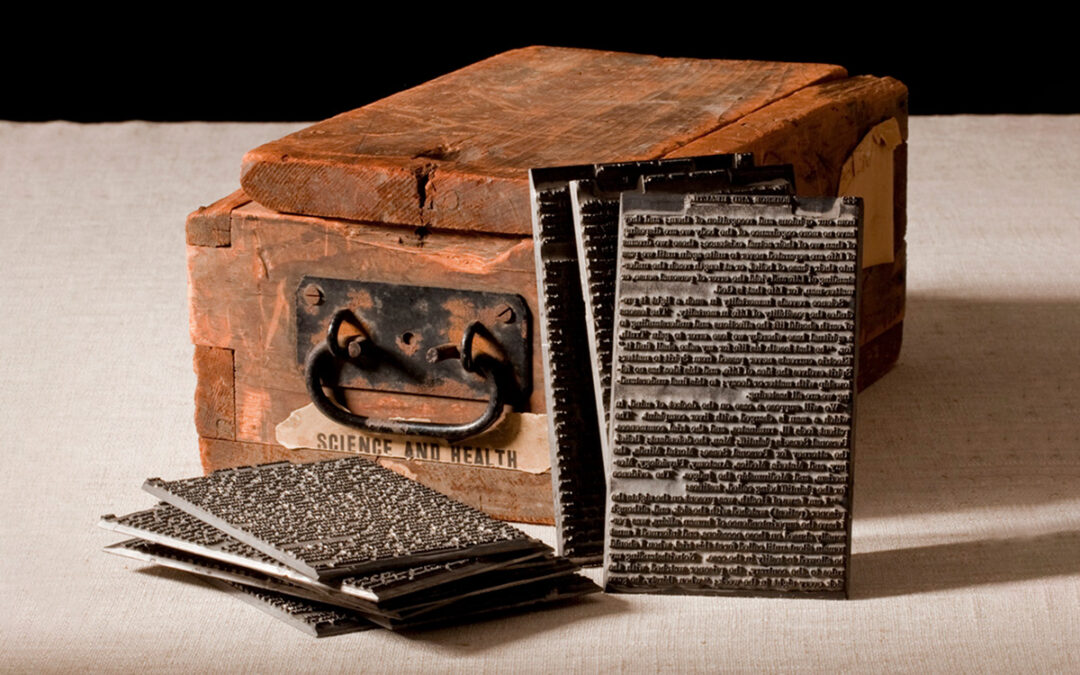

Perhaps some of the more inconspicuous items in the collections of The Mary Baker Eddy Library are a wooden box and a small group of metal printing plates. The box and its contents may seem lackluster—but they are full of history.

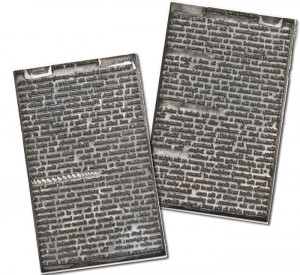

The plates document the first edition of Mary Baker Eddy’s book Science and Health, published in October 1875. They are relics of an era when the production of books was enormously different from the printing and publishing of today. Eddy self-published her books, and in her day this involved finding firms to do the printing and binding. These objects document her struggle to find a capable printer in her price range.

For the first edition of Science and Health, Eddy used W. F. Brown and Company of Boston. Three years later, the second (“Ark”) edition of Science and Health was printed by Rand, Avery & Company, another Boston firm. Like Brown, their specialty was printing brochures and leaflets, not books. It soon became evident to Eddy that the printer could not handle the size and complexity of the work, and typographical errors in the proofs were everywhere.

Eddy needed help. And she found it in John Wilson, of the nationally known University Press in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He helped her salvage the book, and she knew then that he needed to be her printer. University Press took over the work, with the third edition of Science and Health in 1881.

William Dana Orcutt worked for Wilson and assumed responsibility for printing Eddy’s works when Wilson retired. He was involved in the production of her books for about half a century. In 1950 Orcutt recalled what Wilson told him about his early meetings with Eddy:

In April, 1880, there was correspondence between Mr. Eddy [Asa Eddy, Eddy’s husband] and John Wilson concerning the third edition….Nothing came of this correspondence, undoubtedly because Mrs. Eddy was unable to advance one half the cost of the proposed new edition. At all events, she evidently decided to present the case in person, and this explained her presence at the University Press that January afternoon in 1881….Mr. Wilson at this point of the story always emphasized the amazing courage of this woman in meeting the difficulties which had beset her on all sides….Then, at last, they arrived at the crucial point. It was necessary, Mrs. Eddy told him, for her to explain to him the financial plight in which she found herself….Mrs. Eddy admitted frankly that while she could pay perhaps a few hundred dollars on account, she could not possibly advance half the cost as Mr. Wilson had insisted in his letter to her husband. Her only income came from her teaching and from the tenants to whom she rented a part of her house at 8 Broad Street, in Lynn, Massachusetts. If this third edition were produced as she believed Mr. Wilson would produce it, she was confident that she could sell enough copies to meet the cost, but she could not pay in full on delivery. Mr. Wilson never explained, even to himself, his reaction to Mrs. Eddy’s appeal. From a business standpoint there was every reason to decline the whole proposition. “Yet,” he would say, after frankly admitting the situation, “there wasn’t a moment’s hesitation in my acceptance of that order. I knew that the bill would be paid, and I found myself actually eager to undertake the manufacture.” He inquired when the manuscript would be ready. Mrs. Eddy reached into her handbag and produced it, completely finished, ready for the printer. “You brought this on the chance of my accepting it?” John Wilson asked, surprised. Mrs. Eddy smiled. “No,” she replied, “not on a chance. I never doubted.”1

The records tell us that Eddy hoped to give Wilson all the printing plates she had, in order to save costs. But she discovered that Rand, Avery & Company had already destroyed the second edition plates.

Is it possible that this small collection of plates (which cover the final pages of the first edition) was all that Eddy had left to give to Wilson in 1881? And is it also possible that these plates remained with Wilson and his firm for the many years that they printed Eddy’s books?

When Plimpton Press hired Orcutt in 1909, they took over the production of Eddy’s works. And we know that Plimpton deposited over 100 wooden boxes of plates, containing Eddy’s writings, in bank vaults in Concord, New Hampshire, for safekeeping. Was this one of those wooden boxes? We don’t know for sure—further archival detective work is needed. But hopefully an answer will come to light!