In 1604, a process began that would culminate in the publication of the King James Version (KJV) of the Bible in 1611. After publication, this version gained popularity in England because of its accuracy and clarity, not because of its regal backing. For four centuries the KJV has inspired a countless number of people including Mary Baker Eddy. For her the Bible was a teacher and guide from childhood and throughout her life. It was her tireless study of the Bible that helped her define the theology of Christian Science and she later described the Bible as “a complete code of laws, a perfect body of divinity an unequalled narrative.” 1

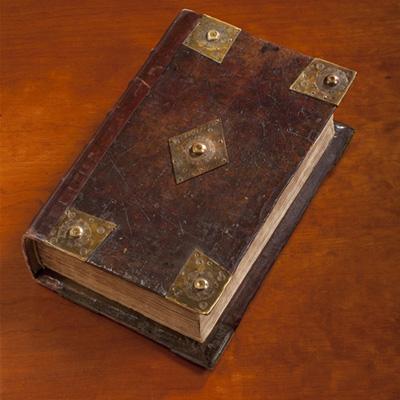

So as the Library celebrates the 400th anniversary of the King James Version it seems appropriate to highlight some features of the first edition, one of which resides in The Mary Baker Eddy Collection. According to renowned Bible Scholar, Donald L. Brake PhD., co-author with John R. Hellstern, of A Royal Monument of English Literature, there are only 174 editions of the original 1611 King James Bible left in the world today out of an estimated printing of around 1500–2000 copies. Brake and Hellstern undertook the first census of 1611 King James Bibles—this census is included in their book.

The process that led to the publication of the King James Version in 1611 lasted seven years and ultimately bankrupted the King’s Printer, Robert Barker. In 1589, Christopher Barker (Robert’s father), renegotiated the royal printing privilege, securing a monopoly on printing the Bible in English, for himself and his heirs. So, even though King James I authorized the translation, the “privilege” and cost of production were always going to belong to the Robert Barker. So Barker set aside £3,500 for the cost of production, and this sizable sum would play its part in Robert Barker spending the last ten years of his life in debtors prison. As he sat in his dark damp prison cell one can wonder if he realized the contribution he had made to the world!

The artwork on the title page was created by Cornelius Boel, a London-based Flemish engraver, born in Antwerp circa 1580. Boel was famous for engravings that depicted biblical scenes and epic battles; he had also painted a portrait of King James I’s son, Henry Frederick Stuart, Prince of Wales. So it seems as though this relationship with the Royal Family is probably why Boel was selected to create the artwork for the frontispiece.

At the very top of the image is the Hebrew name for the God of Israel “YHWH.” These four letters are also known as the “tetragrammaton” and are used by Boel to represent God. In the corners—each one holding a pen— are the evangelists; Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. At the very bottom of the page is the image of a pelican “vulning” (to wound oneself by biting at the breast) her young. In the seventeenth century this popular heraldic motif was used to represent Christ’s salvation of humankind.

The 1611 edition was “appointed to be read in churches,” and the front matter reflects this principal function.

As well as the lectionary the front matter contained a “calendar” identifying the main holy days of the church year, “An Almanack for 39 years,” setting out the main religious festivals from 1603-1641 and a series of instructions to help people work out the exact date of Easter. This collection of material provides a fascinating insight into seventeenth century religious life.