George Glover II circa 1905 (P00804).

Mary Baker Eddy’s only child was her son George W. Glover II (1844-1915), born a few months after the death of her first husband. Like many single mothers of her day, she did not possess the financial means to raise the boy, and before his seventh birthday the two were separated.

George’s life was a rough one, with lots of hard work and little time for schooling. After serving in the Union ranks in the Civil War, he and his young family ended up in Fargo, North Dakota (then called Dakota Territory).

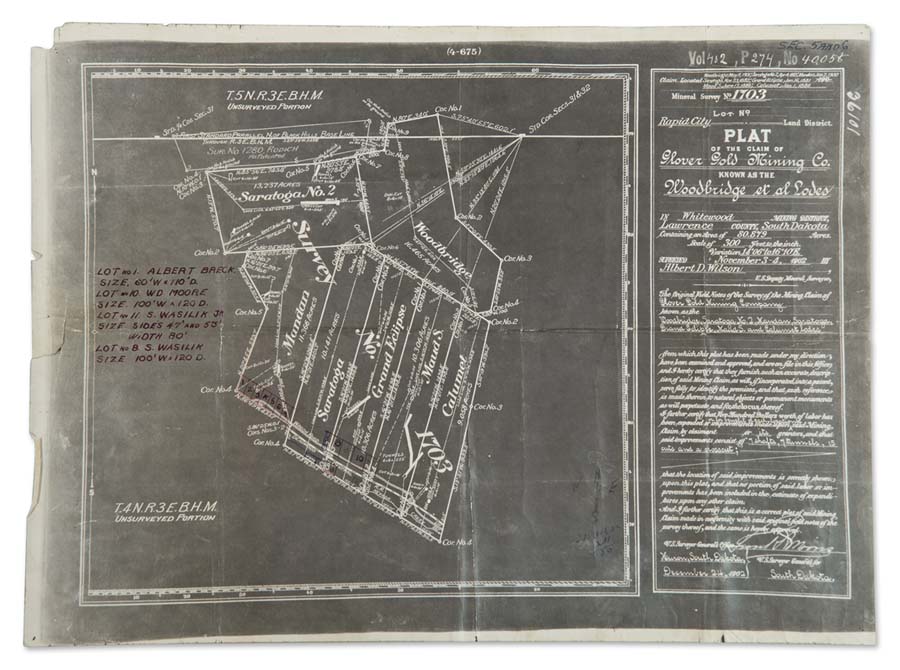

George made an initial visit to the Black Hills from Fargo in early 1878 in order to earn money, so that upon his return to Fargo he would have “feed for his team and seed for his land.”1 It is unclear when exactly Glover returned to his family in Fargo, but correspondence suggests he spent 1878 in the Black Hills. In the spring of 1879 he sold his land in Fargo and moved his family to Deadwood, South Dakota.2 Glover would spend the rest of his life in the Black Hills, prospecting and mining. Eventually he established the Glover Gold Mining Company in July 1900, with his partners Channing M. Woodbridge and James P. Wilson.3 In 1903 the company was granted the land patent for the “Woodbridge et al” claim and took ownership of the land from the United States Government.4 (Land patents are the legal documents that transfer land ownership from the U.S. Government to individuals.)

Early on in George’s mining endeavors, Mary Baker Eddy gave what money she could to help her only child succeed in his prospecting. As time wore on, however, she began to see that prospecting and mining were not an “exceptionally good investment” for George or his family.5 James P. Wilson, who at one time served as Glover’s lawyer and secretary of the Glover Gold Mining Company, commented: “He likes to do good and make people happy but he is bent on being a millionaire and money has for a long time absorbed his entire attention.”6 To counter this, Eddy made considerable investments in real estate to provide her son with an income and a comfortable family home. In doing this she hoped to steer her son away from prospecting and into a line of work that would provide a steady income that enabled her son to better himself and his family. She took a dim view of George’s prospecting: “You [George Glover II] are keeping yourself and your family down by your mining that amounts to but little less than sheer gambling.”7 But the lure of gold had taken hold of George, and his hopeless quest would do irreparable damage to both his finances and his family.

The map of the claim was generated as a result of the mineral survey carried out by the Office of U.S. Surveyor General, as part of the land patent application. The claim was located in the Whitewood Mining District, near Lead, South Dakota. It was made up of seven mineral lodes (the term “lode” referring to a deposit of ore embedded in the rock). These lodes were discovered by various individuals, including George and his son Edward Gershom Glover; however, all the lodes were patented by the Glover Gold Mining Company.8 The law restricted the maximum size of a lode to 1,500 feet long by 600 feet wide, and the purchase price to a maximum of five dollars per acre. The total area of the claim was 80.879 acres, and the Glover Company paid $405 for the claim, along with $898 in application fees. But this was just the beginning of the expenses.

Once a claim had been staked, the claimant was required to perform a minimum of $100 per year in labor or improvements until the land patent was granted by the government. An affidavit signed by Glover and dated 16 January 1903 states that his company had “done more than twenty-five thousand dollars worth of work in shafts and tunnels.” In fact, the results of the mineral survey valued the improvements at $41,465.9 So before any gold had been produced, a minimum of about $26,000 appears to have been expended. Glover’s company also estimated that an additional $75,000 would be needed to “put this property on a paying basis.”10

On April 25, 1903, Mary Baker Eddy received a letter from a Mr. J.W. Gregory—a Christian Scientist representing a mining development company—asking her or an “influential friend” to invest $30,000 in return for 60,000 shares of Glover Gold Mining Company stock.11 Eddy often received such letters; her son’s functional illiteracy meant that all his correspondence was written on his behalf. This also meant that Glover could never know if his scribes were conveying his thoughts or injecting their own.

The $30,000 was to be spent to install machinery and begin extracting ore, Gregory explained. He also noted that he had purchased some stock and believed that once machinery was installed (even before any gold had been produced) the stock would double in price. He suggested that following the installation “stock ought to sell readily at close to a dollar a share, probably more if any should be offered for sale.” Gregory was also keen to state that he was acting without Glover’s knowledge. (This may have been true; in early 1903 Eddy and Glover’s relationship had come close to breaking point following disparaging remarks made by Glover about his mother.)12 However, Gregory seems to have been well informed, because he also enclosed a letter to Calvin Frye, Eddy’s longtime secretary, offering him a $1,500 commission if he could persuade Eddy to invest.13 (This probably reflects George’s suspicion that Frye was controlling his mother’s business affairs.)

To attract other investors, the Glover Gold Mining Company produced a prospectus that talked about the fortune to be made by any would-be investor.14 This bold statement was based on the production figures of the Homestake Mine, which was located close to the Glover Company’s lodes. Between 1876 and 1937, Homestake produced 83.5 percent of all gold and silver in South Dakota (an accredited value of $340,790,554), and the claim would be continuously mined for nearly 125 years.15

Not so for the “Woodbridge et al” claim: “Apparently no commercial ore body was encountered although high values were reported as the shaft was sunk. No production has been reported from the property.”16

Eddy’s response to Gregory’s letter is not extant, but there is no record of her purchasing the stock. In fact, she had returned mining company stock several years before that had been gifted to her by Christian Scientists.17

Nevertheless, George’s pursuit of Eddy’s money for his schemes was relentless. It culminated in his participation in the “Next Friends” suit, a lawsuit designed to prove Eddy mentally incompetent and not in control of her business affairs—a sad denouement of their relationship. As biographer Gillian Gill notes, Glover “gained nothing by [the] suit but more debt, a heavy weight of public opprobrium, and worsened prospects.”18 It seems that Glover, whether gambling in the courts or in the mines, could not win.

- Harriet Ellen Glover to Mary Baker Eddy, 14 January 1878, IC197.

- George Glover II to Eddy, 12 August 1879, IC197.

- Land Entry Case File 36101, Rapid City, South Dakota Land Office, of Glover Gold Mining Company, 1903.

- “Land patents,” accessed July 18, 2014, http://www.archives.gov/research/land/.

- J.W. Gregory to Eddy, 25 April 1903, IC197.

- James P. Wilson to Eddy, 15 April 1903, IC590.

- Eddy to Glover, 2 December 1897, L02125.

- Land Entry Case File 36101.

- Ibid.

- SF – Glover – Mining, Articles, Prospectus, Clipping.

- Gregory to Eddy, 25 April 1903, IC197.

- Eddy to Glover, 7 April 1903, V00392.

- Gregory to Calvin Frye, 25 April 1903, IC197.

- SF – Glover – Mining, Articles, Prospectus, Clipping.

- Paul T. Allsman, “Reconnaissance of Gold Mining Districts In The Black Hills, S. Dak,” Bulletin 427, Bureau of Mines, 1940, 8.

- “Black Hills Mineral Atlas, South Dakota: Part 1 (in two parts),” U.S. Bureau of Mines Information Circular 7688, 1954, 81.

- Eddy to Ada M. Surbaugh, 2 July 1900, N00281.

- Gillian Gill, Mary Baker Eddy (Reading, MA: Perseus Books, 1998), 520.