The growth of the Christian Science movement in the early 1880s was due in part to Mary Baker Eddy’s skills as an orator, teacher, and entrepreneur. Ably assisted by her husband and students, she progressively grew her church, and services in parlors soon moved to rented halls. By the end of 1894, The Mother Church had a permanent home in the Back Bay section of Boston. This month’s objects—her calling cards and business cards—played a small role in this journey, helping to open doors so she could open minds.

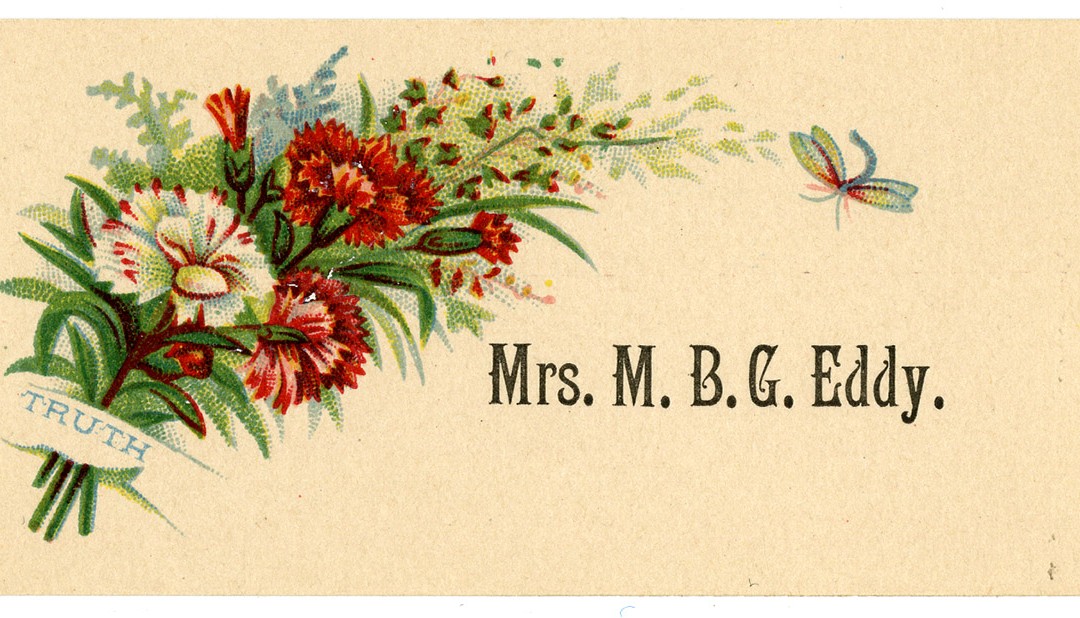

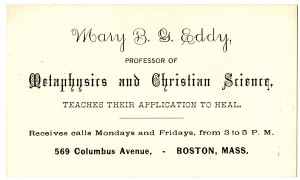

The use of the word “Truth” on Mary Baker Eddy’s colorful calling card (undated) suggests that Christian Science had a role in her social calls. In contrast, her business card (circa 1882) is black and white, and focuses on her work as a Christian Science teacher (1984.37.431.8.2, 1984.37.352).

While American author Emily Post commented that “with a hair-pin and a visiting card, [a lady] is ready to meet most emergencies,”1 Mary Baker Eddy certainly needed more than “a hair-pin and a visiting card” to share her discovery of Christian Science with the people of New England. Yet business and calling cards did play a part in helping Eddy promote her work as teacher, lecturer, and healer, particularly as she transitioned from Lynn, Massachusetts, to Boston in the early 1880s.

Today exchanging business cards is an informal way to distribute personal information for business or social reasons. Before the telephone became a means of communication, however, nineteenth century social etiquette required people to have a calling card (for social calls) and a business card (for business calls). An unannounced social visit to a friend or an acquaintance required a calling card to be presented on arrival to whomever answered the door, whether that was a servant or the lady of the house. If one was greeted by a servant, the card would be taken to the lady of the house; if she was out, the card would be left with the servant. If a visit took place at a hotel or a boarding house, the card went up to the room via waiter or bellhop and the visitor would wait downstairs in the parlor, where the face-to-face visit would take place.2

Calling cards were particularly useful for Eddy and her students. Christian Scientists traveled from all over the United States to take classes at the Massachusetts Metaphysical College, and they would leave their calling cards with Eddy or her secretary, Calvin Frye, to let her know they were in town and where they were staying. Eddy would then leave her calling card with students, to let them know when and where they could visit her.

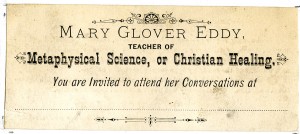

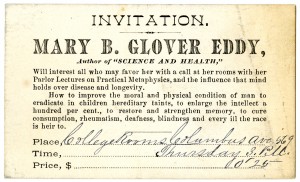

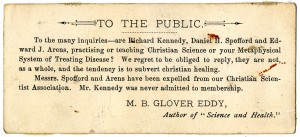

Calling card-size invitations to “parlor lectures” and “conversations” given by Mary Baker Eddy (SF – Eddy, Mary Baker – Calling cards).

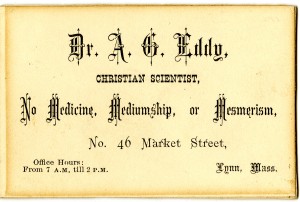

The importance of business cards as a means of identification cannot be underestimated. The New Thought movement of the late nineteenth century created a spiritual and metaphysical maelstrom, and Eddy and Christian Scientists were often identified with mesmerism or spiritualism. Eddy used her business card to establish credibility and clarity in this metaphysical muddle, and in 1886 she wrote to a number of her students about the importance of using uniform language on business cards and diplomas, saying this: “To command the public respect we must have uniformity in our System of public Schools and in the line of other educational methods. The good work of my good Students contrasted with the evil and ignorance of other claimants calling themselves Presidents and Professors …. In view of all this we have adopted the following Rules.” The First rule was “Give the name Christian Scientists to all business cards and identify your School by this name….” 3

In fact, Eddy’s business cards document the evolution of the term Christian Science, for she initially refers to her discovery on her cards as “Metaphysical Science” and “Christian Healing.” Eddy’s business cards, and those of other Christian Scientists, were also used to carry statements differentiating Christian Science from the offshoots of New Thought.

A business card (undated) of Mary Baker Eddy and the business card (circa 1876) of her third husband, Asa Gilbert Eddy. Kennedy, Spofford, and Arens were former students of Mary Eddy who had become involved with mind-cure movements (SF – Eddy, Mary Baker – Calling cards, 1984.37.349).

Mary Baker Eddy began lecturing on Christian Science around the time that Science and Health was first published in 1875. She spoke in small towns and large cities, in public and private halls, house parlors, and church auditoriums. She lectured to groups of all sizes—beginning with gatherings of ten, then to congregations numbering in the hundreds, and later in the thousands. Eddy and her students used their business cards to distinguish them from other religious groups, helping to facilitate and strengthen the growth of the fledgling Christian Science movement.