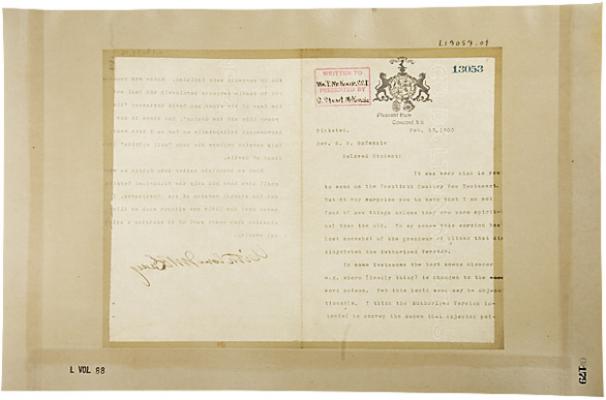

Silked letter by Mary Baker Eddy to William P. McKenzie February 2, 1900.

With all the focus on digitization of documents today, it’s easy to forget that preservation is not a new issue. In fact, proper preservation of Mary Baker Eddy’s letters and manuscripts was first considered over 90 years ago.

In 1917, the Christian Science Board of Directors put notices in the Christian Science Sentinel that announced the Church’s interest in donations of items written by Eddy for the archives. Preservation work on the letters and manuscripts had started earlier, in 1916. Almost all of the work was undertaken in the Extension of The Mother Church, where there was room for this project. Eventually the bound volumes of the letters and other manuscripts were kept in a climate–controlled vault in the extension.

The Emery Preserving Company of Taunton, Mass., performed the preservation work. The company was founded by Francis Walcott Reed Emery, a bookbinder who made mainly blank books. In 1891, Emery was treating fragile documents by stabilizing them with tissue; by 1894, he had added silk lamination to his product line. Emery changed slightly his product to lightly coat the silk with paraffin wax; he was then able to obtain a patent. His silking process was widely accepted as a standard well into the 1930s.

Before the documents were backed with silk, they were immersed in a paraffin wax solution and hung up to dry. Florence W. Saunders, a Mother Church employee, explained the technique in 1932.

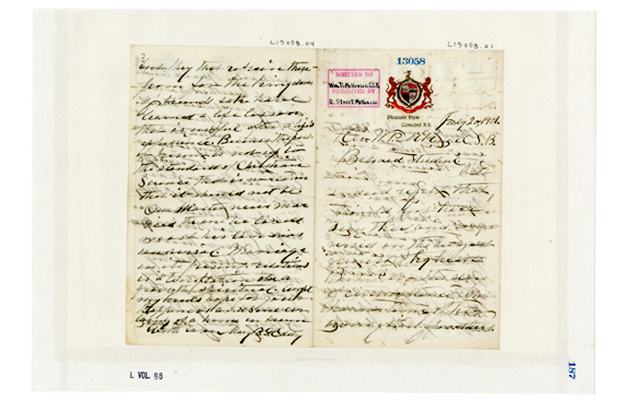

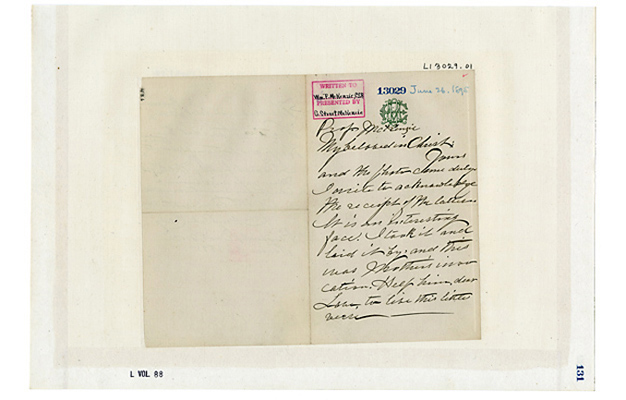

The Company takes a large sheet of the heavy paper upon which the letters are to be mounted, and a section of this paper is cut out, allowing the insertion of the letter, and a very narrow margin is allowed – merely sufficient to hold the letter. Over this is pasted a sheet of very thin silk, which is obtained from France, and over the edges of this silk, in order to keep them from fraying, is pasted a thin strip of tissue paper. The entire page is then put into a press and subjected to a very heavy weight. It is left there sometimes as long as forty–eight hours, and it comes out in perfect shape, without any wrinkles, and is very legible…1

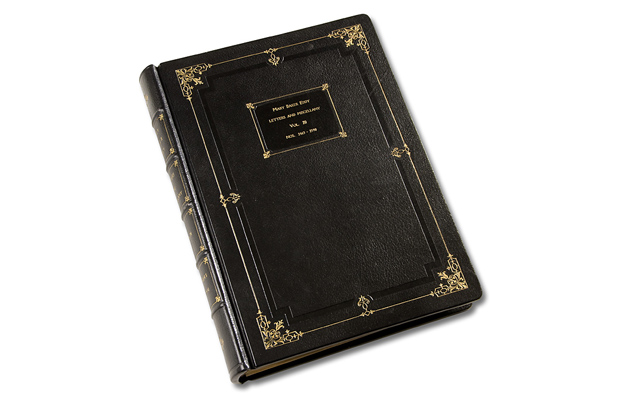

After the documents were silked and dried, they were bound into leather embossed books for storage in the vault. Saunders describes this method.

A number of pages are then sown together in regular book-binding manner, and then the binder comes to the church with his tools and the leather, which is obtained in England. The leather covering is made at the church, and the contents fitted in but not finally attached. The cover is taken to Taunton, where it is hand–tooled and the gold applied. It is then returned to the church, where it is permanently attached to the contents….2

The documents were organized by accession number—a unique identifier that is assigned to each letter or manuscript. Typed copies of the documents were made so staff could access them regularly. A card index was also made for easier searching by keyword or by subject. This way the original letters in the leather bindings were handled as little as possible to aid in preservation.

In 2001, when The Mary Baker Eddy Library was getting ready to open its doors, staff was given permission by the Christian Science Board of Directors, the owner of the collection, to remove the documents from the leather books. Each book contained 500 silked pages and there were 120 volumes. The silked pages were then laid flat on a scanner so digital images of documents could be added to a database searchable by staff and patrons. Additionally, once out of the bindings, single documents could be used in exhibits. The letters and manuscripts currently reside in archival boxes and are stored in a climate–controlled environment in the Library.

Today silking is no longer used as a preservation technique. Though it is not considered a present day archival preservation standard, this method certainly kept Eddy’s letters in beautiful condition, for all of us to research and enjoy today.