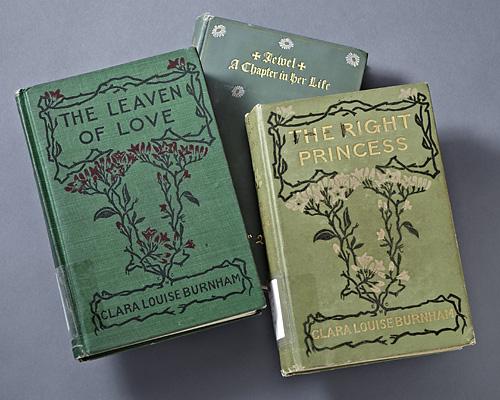

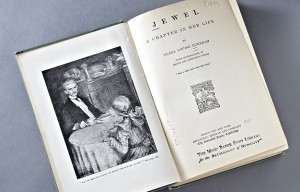

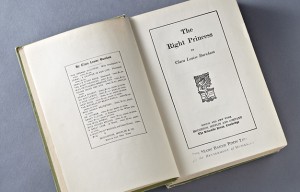

The American author Clara Louise Burnham wrote 26 novels between the years 1881 and 1925. Amongst these were Christian Science themed fiction: The Right Princess (1902), Jewel (1903), and The Leaven of Love (1908). These three novels are considered her “Christian Science trilogy.” Burnham’s short stories and novels enjoyed widespread success and were well received, and several of her books were adapted for stage and screen.

Burnham was born Clara Louise Root in Newton, Massachusetts, on May 26, 1854. She was the daughter of Dr. George F. Root, a composer famed for his American Civil War songs, such as “The Battle Cry of Freedom” and “Tramp, Tramp, Tramp, the Boys Are Marching.” Her brother Frederick W. Root was a musician who wrote both hymn texts and one hymn melody found in the Christian Science Hymnal. The Root family moved to Chicago, Illinois when Clara was a child, and she spent the rest of her life living between Chicago and her summer home at Bailey’s Island, Maine, where she died June 20, 1927.

Burnham, a Christian Scientist, sent an advance copy of The Right Princess to Mary Baker Eddy, which Eddy enjoyed reading, saying that the novel was “a rare production in the line of fiction.”1 Eddy praised The Right Princess and Jewel in private and in public. After receiving a copy of Jewel, she sent copies to her cousin Hon. Henry Moore Baker—a New Hampshire lawyer and politician—and to Edward Augustus Jenks—a local poet. Eddy reported to Burnham that both men “were pleased with it.”2

The Christian Science Sentinel printed an announcement by Eddy praising The Right Princess. Eddy said of Burnham: “The author dissects character with the skill of a metaphysical surgeon: she uses the knife and leaves the patient healed. She has portrayed a Christian Scientist with simplicity and candor: her pen is the pencil of an artist.”3

Despite her praise for The Right Princess, Mary Baker Eddy did not approve of the ending, asking Burnham to clarify whether the characters Frances and Burling get married or just remain friends. In a letter dated September 10, 1902, Eddy wrote to Burnham about this:

Here is the point I ask: Please make your meaning plain at the close of your book. As it now is its secrecy is enchanting. But my dear friend, you can make your Princess the heroine to refuse marriage and retain the love of her lover in the purity of spirit in your admirable style and that would turn passion into sentiment….4

Eddy also requested Archibald McLellan, Editor of the Christian Science periodicals, to contact Burnham and ask if she could amend the ending.5 McLellan asked Burnham: “Can you not … definitely define the attitude of Mr. Burling and Frances as friends and not leave the reader to infer that they marry?”6 However, it was too close to the publication date for the first edition, and Burnham explained to McLellan that she hoped her publisher, Houghton & Mifflin, would agree to publish revisions at a later date.7 Burnham wrote an additional chapter titled “Whither thou goest” that was never published, though there is a copy of the manuscript in our collections.8

Eddy’s endorsement of The Right Princess and her reconsideration of that endorsement meant that she also had to reconsider the role of The Christian Science Publishing Society in advertising and selling such literature. On September 25, 1902 she sent a telegram to Burnham saying “God has spoken and this, it is not right for Christian science press to advertise fiction in any form.”9 Simultaneously Eddy also made an amendment to the Church Manual By-Law “Rule of Conduct” (now Article XXV, Section 7), adding the sentence “Novels shall neither be advertised nor sold by the Christian Science Publishing Society.” This sentence was published in the 27th and 28th editions of the Church Manual (both 1902).

While Clara Louise Burnham’s fiction may not be well known today, her popularity went well beyond the Christian Science community, as one biographer noted: “To write twenty-six books is something, is it not? To have written twenty-six books which have sold half a million copies (the publisher’s offhand guess) is something else again and more. Clara Louise Burnham has done that; and the cold arithmetical statement does not begin to convey the real nature of her achievement. You must read her to know how capable a novelist she is, how expert, how gifted with humor, insight, fertility in those slight inventions which make up the reality of a fictionist’s whole….”10

- Mary Baker Eddy to Clara Louise Burnham, 10 September 1902, L08337.

- Eddy to Burham, 4 January 1904, L08340.

- Mary Baker G. Eddy, “Question Answered,” Christian Science Sentinel, October 2, 1902, http://sentinel.christianscience.com/shared/view/1z9p0hfo33i?s=t.

- Eddy to Burnham, 10 September 1902, L08337.

- Eddy to Archibald McLellan, 10 September 1902, L03032.

- McLellan to Burnham, 11 September 1902, IC 5a.

- Burnham to McLellan, 16 September 1902, IC 48.

- Burnham, IC 48.

- Eddy to Burnham, 25 September 1902, L09170.

- Grant M. Overton, The Women Who Make Our Novels (New York: Moffat, Yard & Co., 1918), 267.