Women of History: Dorothy Adlow

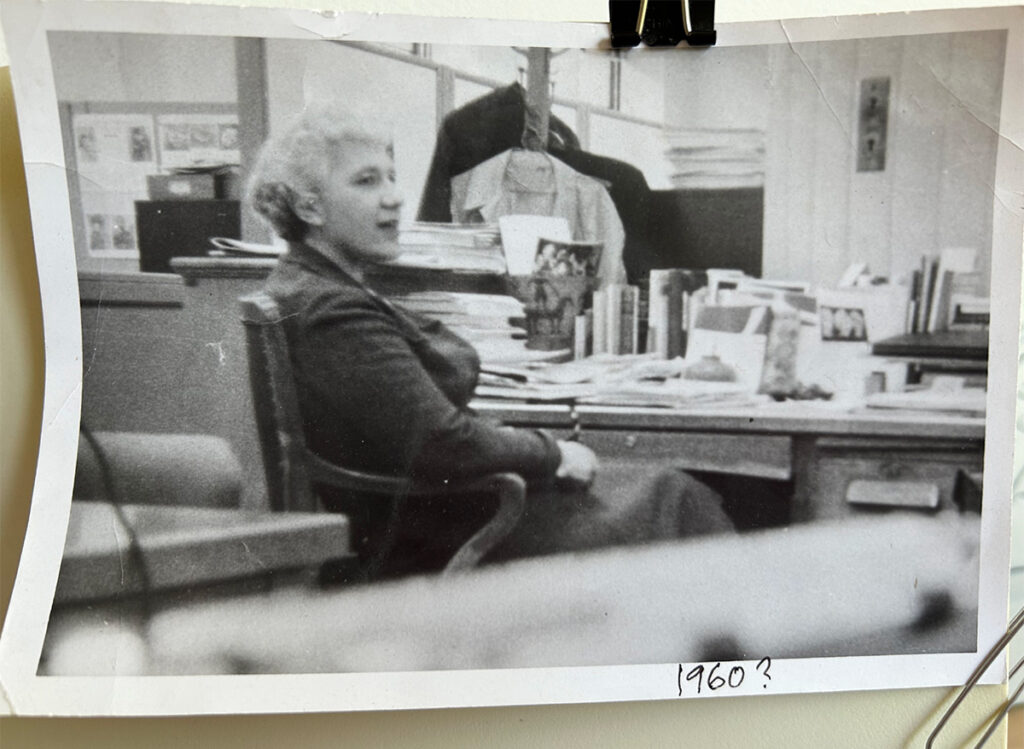

Portrait of Dorothy Adlow, n.d. Courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

In 1960 the famed illustrator Norman Rockwell sent a note of thanks to The Christian Science Monitor’s long-serving art critic, Dorothy Adlow (1901–1964). “Maybe this is unethical but I can’t resist writing you and telling you how much I appreciate the review you wrote,” he told her. “To tell you the truth I was scared to death about the reviews but your review was so kind and thoughtful, I feel reassured.”1

In that case, Adlow was not operating in her usual role of reviewing exhibitions but rather commenting on Rockwell’s recently released autobiographical work, Norman Rockwell: My Adventures as an Illustrator. Still, Rockwell’s words mirrored those of a wide range of twentieth-century artists who found in Adlow a penetrating critic who offered insight and understanding they trusted and valued.

A robust career

Adlow wrote art reviews for the Monitor for just over 40 years. To explore her work is to receive a comprehensive education in art history. Longtime Monitor editor Erwin Canham noted this in a foreword to a book manuscript of Adlow’s work (as yet unpublished):

Men and women living on remote ranches, far from any museum or collection, often wrote her in gratitude for the windows she opened in their lives. Yet the expert did not turn his nose up at her writing, for it was as sound as it was clear.2

Canham’s tenure as the newspaper’s managing editor, and then editor, overlapped significantly with her career there.

Dorothy Adlow, c. 1960. Courtesy of Electra Slonimsky Yourke.

Many of Adlow’s reviews were necessarily short, fitting into a measured amount of available print space in a global newspaper that provided comprehensive news coverage. Still, both her long- and short-form work was avidly followed and respected, both in artistic circles and by the general reader. Curators, museum directors, and art historians admired and sought out her perspective and criticism. Through these associations, a strong spirit of collegiality developed over the course of her career with leaders in the American art world. Among them was James Johnson Sweeney, director of New York City’s Guggenheim Museum. “Dear Dorothy,” he wrote, in response to Adlow’s review of a 1957 exhibition, “you were very kind to us in your review of the current show.” He continued, “It amazes me how few reviewers look at pictures. It always shows in their stories and the way you look at pictures always shows in yours.”3

A gifted critic

Adlow’s review of Sweeney’s international exhibition was a case in point of her ability to both describe an artwork with an economy of words and place it within a larger cultural and historical context. Commenting on “Portico” by Juan Miro and J. J. Artigua, she explained that it included “nine oblong sections, resembling stone” and was “decorated by two methods: the impress of the human foot, and freely devised painted motifs such as crescent shapes, disks, stars.” She then summarized that “there is about this portico a sense of agelessness. Nothing in it reflects the 20th-century world, except an absolute contrariness on the part of the artist in his reaction to materialism, mechanization, and standardization.”4

For Monitor readers and devotees, Adlow’s final line on the Miro/Artigua piece would have stood out. Although a secular news organization, the Monitor’s approach to covering world events drew, and continues to draw, from the vision of its founder, Mary Baker Eddy, leader of the Christian Science church. As Canham noted in Commitment to Freedom: The Story of The Christian Science Monitor, “this fundamental concern with spiritual values gives the paper its confidence in man’s best self and in the triumph of decency.”5 Insofar as modern art has urged an expanding view of what constitutes the reality of human experience and of the cosmos, its purpose would have found a degree of common cause with Canham’s next statement about the influence the Monitor’s spiritual ethos had on journalism: “It does not impair, but enhances, its ultimate realism.” Sculptor George Aarons’s 1931 bust of Adlow, with its emphasis on the concentrated look of her eyes, suggests a recognition of her commitment to seeing deeply into the work she was covering.6

Bust of Dorothy Adlow, 1931. George Aarons. Staff photo.

But Adlow maintained a strong independent voice throughout her career, which at times could challenge some Monitor subscribers. Her reviews and commentary found space in its pages on an almost daily basis, many of which appeared in the paper’s “Home Forum”—a section dedicated to cultural and spiritual topics. Of these contributions, this reader expressed gratitude:

For many years I have both enjoyed and been slightly amazed by Dorothy Adlow’s little articles in the Home Forum page. It seems that there is hardly an art subject on earth, past or present, that she is not qualified to write informatively about. So engagingly does she do so, that through simple means alone we gain insight in the manner and customs, not only of the artists themselves, but the times and manners of the subjects themselves.7

The Monitor also featured longer reviews by Adlow. A six-part series she wrote in 1963, “Roads to Understanding: Modern Art,” drew widespread interest. Some 14 years earlier, the United States State Department had asked for “permission to distribute to State Department missions in continental Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, the Far East, and Africa for translation and possible republication in local periodicals ‘Van Gogh Retrospective Show’ by Dorothy Adlow.”8 She also wrote “‘Twentieth Century Highlights of American Painting,’ a catalog for a traveling United States Information Agency exhibit.”9 Whether through the Monitor as a global newspaper or other channels, Adlow’s reviews had what its editor prized as “a world-wide audience.”10

Boston birth and background

Although Adlow’s reach was international, she was in many ways very much a Bostonian. Born at the beginning of the twentieth century to a Jewish family in the Roxbury section of the city, she experienced both the cultural influences that reflected the Old World from which her parents had come and the educational opportunities afforded by their new home city. Both parents were immigrants. Her mother, Bessie Bravman Adlow, had come to America from Lithuania; her father, Nathan Adlow, from Poland. Neither of them had received much in the way of schooling, and they leaned on familiar customs when settling into a new land. Electra Slonimsky Yourke, Adlow’s daughter, has noted that “the traditions of the old country were constantly maintained and reinforced” and that “there were prayers in the morning and before meals, and the Sabbath was strictly maintained.”

Roles for female members of the family were particularly limited in connecting with the larger society: “Women worked in the kitchen in a seemingly endless round of scrubbing, cooking, cleaning, laundry, and dressmaking, and the daughters helped in each task.”11 Yet prosperity came as Nathan Adlow became a successful furniture store owner. This newly acquired affluence opened avenues to higher education for both boys and girls in the family. Dorothy and all her sisters attended Boston’s prestigious Girls Latin High School. Her brother, Elija, obtained degrees from Harvard University and Harvard Law School, and went on to hold important positions, including as Chief Justice of the Municipal Court of the City of Boston.12 Likewise, Dorothy pursued higher education at Radcliffe, then the women’s college associated with Harvard. There she earned a bachelor’s degree in 1922 and a master’s in 1923. After Radcliffe, she had a short stint with the Boston Evening Transcript, and then began her career with the Monitor.

Marriage and family

In 1931 Dorothy married the mercurial musicologist, conductor, and composer Nicolas Slonimsky (1894–1995). Of their union her daughter, Electra, wrote:

Here is a beautiful young woman, clear of voice, proud, and self-confident. As early as her mid-twenties, she has achieved independence, self-sufficiency, and professional status, despite family opposition and the larger society’s reluctance to open its social, professional, or economic doors to women…. Here is a talented, neurotic young man in his early thirties. He is rather charismatic, multilingual, a local celebrity as a conductor of modern music, and assistant to the conductor Serge Koussevitzky.”13

Despite Slonimsky’s formidable abilities, Adlow was the more reliable breadwinner for the family: “She was what is now called imbued with the work ethic,” observed Electra. “She worked steadily, met all the deadlines, and essentially provided the baseline income, small as it was, on which the household depended.”14

Nicolas Slonimsky and Dorothy Adlow, 1949. Courtesy of Electra Slonimsky Yourke.

Dorothy also opened doors for her husband at the Monitor. According to David Miller in the Journal of Musicology, “In 1936, she arranged for Slonimsky to write articles on music for the Monitor’s Children’s Page.”15 Their household served on occasion as a Boston salon of sorts. As Monitor writer Roderick Nordell remembered in a tribute, “To go to a gathering at the Slonimskys’ was to be immersed in art, music, and topics of the day.”16

Boston Artists

While Adlow’s reviews included artists from across time and the world, she devoted considerable attention to local artists, many of whom developed strong international reputations. Local galleries allowed her to study and get to know key figures in the arts in her own backyard. For her, Boston was prim and proper—and at the same time a seat of artistic daring and experimentation. In a diary entry from early in her career, she made these observations:

Charles Street…cleansed and purged with sandblast and paint…is quite aristocratic and Bostonese…with its numerous antique shops featuring violet and gold (lustres?), colored glass, hook rugs, cabinets…. The windows sparkle—there is too much “arrangement”…antiques must always retain the odor of the attic and an association with a mild muddle. Foodshops show too dainty cakes, little rabbits and brownies and prismatic icings, marmalades in bottles. Things quite “extra speshul” for people that have taste and especially money.”17

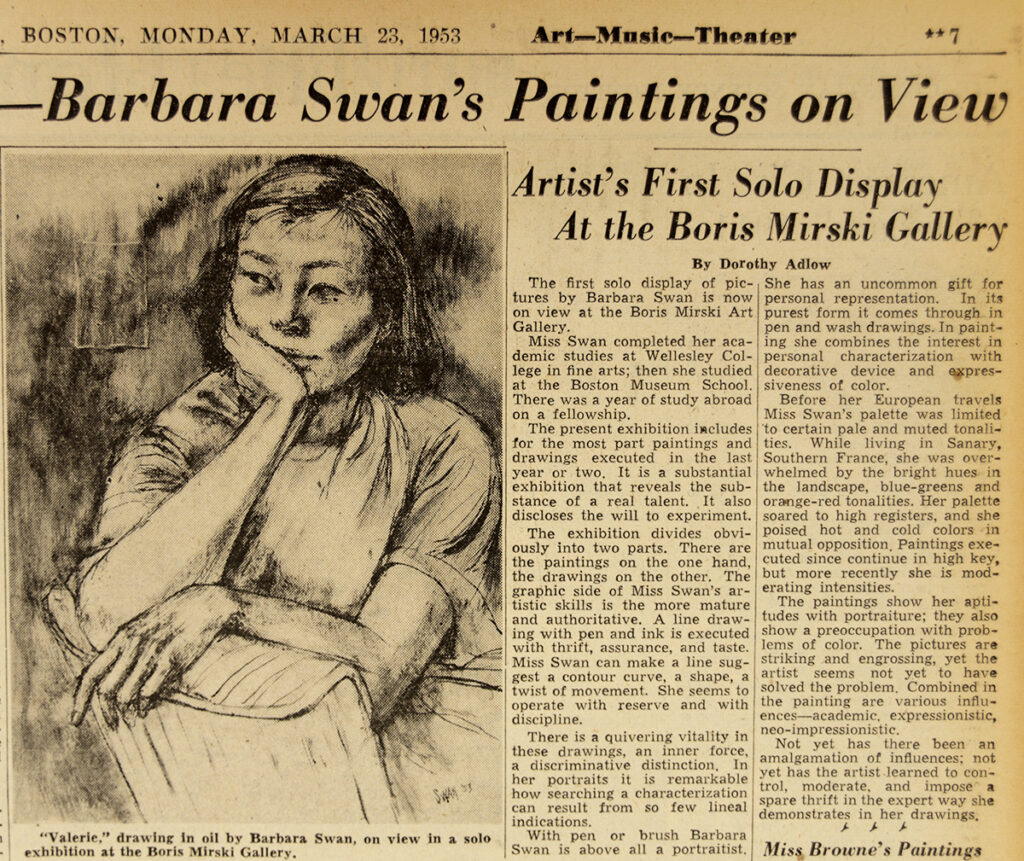

On the other hand, Charles Street was home to the Boris Mirski Gallery, which “created opportunities for artists working against the generally conservative tradition of the Boston School, and helped establish an identity for the local avant-garde.”18 Adlow developed strong relationships with many of the Mirski fold, a number of whom came to be known as the Boston Expressionists. Included among them was Mitchell Siporin, Bernard Chaet, David Aronson, Barbara Swan, Karl Zerbe, and Hyman Bloom—names that would earn distinction in the art world as well as in the academy, including at Yale, Brandeis, Boston University, and the Museum School at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Hyman Bloom was perhaps the most impactful of the group, described by Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning as “the first Abstract Expressionist artist in America.”19

Dorothy Adlow, “Artist’s First Solo Display At the Boris Mirski Gallery,” The Christian Science Monitor, March 23, 1953, 7.

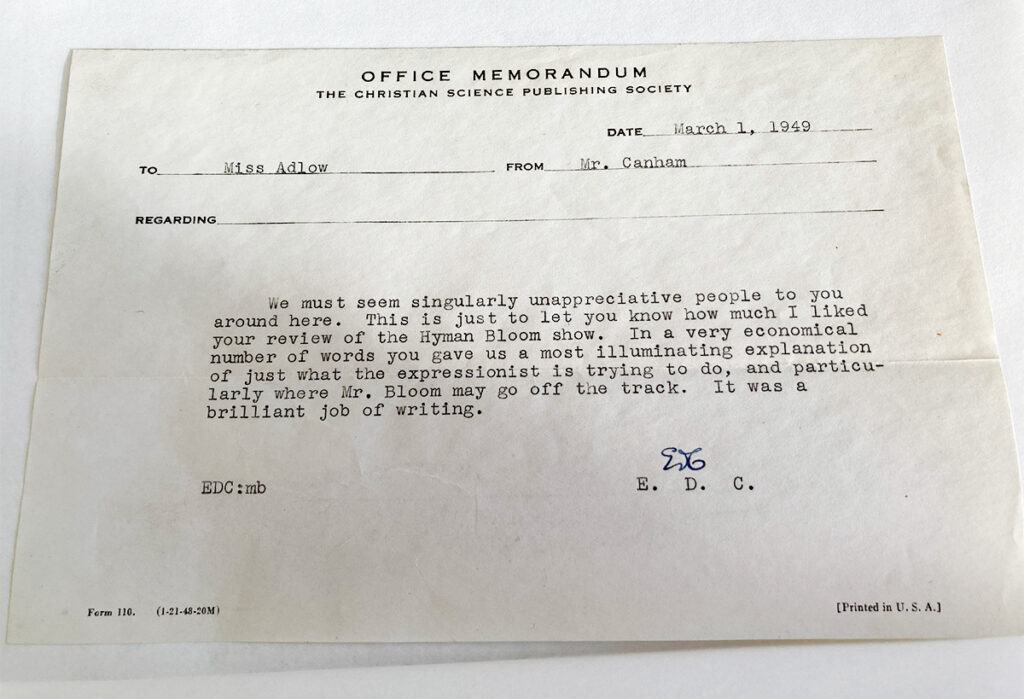

Adlow was on the cutting edge in recognizing the value of these artists’ output. Canham acknowledged that the Monitor’s Home Forum page was “slow to admit contemporary styles in art, but did so in the 1950s after they had become fully established and recognized as part of the canon by galleries, schools, and critics.”20 Still, in a March 1, 1949, memorandum to Adlow, he expressed admiration for a piece she had written on Bloom. “We must seem singularly unappreciative people to you around here,” he commented. “This is just to let you know how much I liked your review of the Hyman Bloom show.”21

Adlow was early in bringing attention to Bloom’s work. In a November 15, 1945, review, she observed:

Few Bostonians know Hyman Bloom, but those who do have evolved something of a legend about him. . . . Feeling is at the core of all his handiwork, and some of his compositions have paraphrased feeling in modulations of color and with a rhythmical interplay that is deeply stirring.”22

Her capacity to discern and embrace the deeper motivations that spurred these artists’ works was recognized and appreciated. In an article on the Boston Expressionists, Bernard Chaet remembered Adlow’s contributions:

She chronicled our development and gave constructive criticism. Her views were independent, her thoughts beautifully and precisely phrased. Every exhibition received careful scrutiny, and she could say a lot in four paragraphs. She is missed by those of us who grew up with her inventive prose.23

Objections

Adlow’s openness to new and challenging forms of artistic expression brought occasional complaints to the Monitor. One such case pertained to Time magazine’s featuring of her selection for a “Critics Choice” exhibition at the Cincinnati Museum of Art. Adlow recommended the work of Nathaniel Jacobson, a young Boston artist, in his portrayal of a gaunt and naked figure resurrected from the valley of dry bones, as depicted in the book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew and Christian Bible.24 One Monitor subscriber did not hold back in condemning the decision. In a letter to Canham, she explained:

I am a member of a Monitor circulation committee, but I feel that it will be a long time before I care to mention the C.S. Monitor to anyone. Many other people who read Time Magazine will be much surprised that such a picture could be associated with the Christian Science Monitor.25

Canham exercised some degree of legerdemain in his response. “Miss Dorothy Adlow, who was referred to in the Time magazine article, is not a member of the staff of The Christian Science Monitor,” he noted. “She is an independent art critic from whom we purchase articles on their merits,” adding that “although Miss Adlow was presented as our critic in the Time article, she did not actually represent The Christian Science Monitor in this judgment, and we had no part in the decision.”26 Given that Adlow’s articles had been appearing continuously in the paper, and that Canham would recognize her as an important contributor to Monitor journalism, his response suggests the threading of a tight needle between what was technically true and factual in practice and spirit.

Canham did fare somewhat better by Adlow when responding to inquiries about her potential Communist sympathies, and those of her husband, during the “red scares” of the McCarthy era. In a memorandum dated July 20, 1950, Canham explained, “The best judgment of those of us who know Miss Adlow is that she is not a Communist, although she appears to be an intellectual liberal, and the same appears to be the case with her husband.”27

Erwin D. Canham to Dorothy Adlow, March 1, 1949. Staff photo.

Awards and distinctions

In addition to being a writer, Adlow was a public figure. She lectured throughout the United States, including on television. In 1930, early in her career, she was the first woman to lecture at the Carnegie International Exhibit Series in Pittsburgh, the longest running exhibition of international art in North America. At her twenty-fifth class reunion, Radcliffe College honored her with membership in the Iota Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa. In 1953 the American Federation of Arts bestowed on her its Arts Critic Award, and in 1957 she received the Art Citation of Merit from Boston University.28

She was the only woman to receive the honor that year. Shortly after her death in 1964, Richard “Diggory” Venn, head of education at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, commented on her significance. “The late Dorothy Adlow, nationally known and respected art critic of The Christian Science Monitor, was above all a friend, in a personal and institutional sense,” wrote Venn. “Much in demand as a lecturer, she refused far more lucrative offers in favor of her regular Sunday talks at the Museum. Her lectures were sturdy, vital, fair, informed, and immensely popular.” He added, “With typical open-handedness, she offered her services to the demanding and unfamiliar medium of television, during the interim year when we had no television lecturer.”29

Conclusion

In a piece titled “Let the Critic Be Humble,” published in the Monitor on November 9, 1954, Adlow gave a measure of insight into her philosophy of art criticism. There she argued against holding to a strict allegiance to what one likes, and to be open to new ways of seeing and experiencing art. Emphasizing the male pronoun to represent the critic—a practice that can sound off-putting to twenty-first-century ears and minds—she summarized the art critic’s task in the kind of clear and sound terms that Canham called out as a trademark of her writing:

We who try to serve as art critics are not concerned primarily with discussing what we like. Our task is broader; and for the most part it is impersonal. A critic strives to see a work of art from the point of view of the artist. He tries to figure out how efficiently, how effectively the artist has gained his objective. A critic studies and ponders a work. He may look for influences, or sources of inspiration. He searches for meaning and significances. He tries to discern the caliber of workmanship, the quality of skill. He explores a work for the interest of the subject, for the expressiveness of feeling. He is interested in discovering how this picture relates to human experience.30

Examples from Adlow’s massive body of work for the Monitor provide consistent and marked evidence of applying these principles in her reviews. In a commentary on illustrations by the English poet and artist William Blake, on display at the Pierpont Library in New York City, Adlow conveyed the singular qualities that distinguished the work of this spiritual visionary. “Blake was positive and dramatic, but never harsh; he was closer in spirit to the Gothic,” she wrote. “While he had a superb decorative sense, his drawing was purposeful and compact in statement of a literary or mystical idea.” On his engravings, she concluded, “There is nothing to compare with them for perfection in fulfillment of ideas, for magnificence in execution. They disclose him as a master craftsman ranking with the greatest.”31 While not everyone might have agreed with Adlow’s estimation of Blake’s work, she gave readers tangible qualities to look for when attending the exhibition.

For contemporaries, Adlow was a critic they took seriously. Correspondence she received repeatedly communicated gratitude and respect for her perception into, and articulation of, their work. “When I finished reading your review in THE CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR, I had the unusual feeling of having been interpreted wholly, and having my work perceived in a continuity,” wrote the social realist painter Mitchell Siporin. “What you wrote on Monday helped me to feel the continuity of my effort, and the patterns you discerned make sense not only to me but for the people who read you.”32

For the newspaper that featured her work for over four decades, Adlow helped serve its mission by offering sensitive and compassionate insight into the work and objectives of the visual artist, both historically and in the current moment. As Canham noted, “The Christian Science Monitor is very grateful for the warm cultural values Miss Adlow brought to its pages. They were a reader service all too rare in daily journalism. They were manifestly more than art criticism…. They were popular education of the most excellent sort.”33

- Dorothy Adlow Papers, 1923-1969 (DAP); Norman Rockwell to Dorothy Adlow, 19 March 1960, A-138, folder 13. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- DAP; Erwin D. Canham, “Foreword,” Roads to Understanding Modern Art by Dorothy Adlow, edited by Frances Sharf Fink, unpublished manuscript, A-138, folder 17. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- DAP; James Johnson Sweeney to Dorothy Adlow, 31 July 1957, A-138, folder 14. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- Adlow, “Frontier Explorations in Guggenheim Show: Unexplored Byways,” The Christian Science Monitor, 20 July 1957, 8.

- Erwin Canham, Commitment to Freedom: The Story of The Christian Science Monitor (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1958), 437.

- See Edgar Driscoll, “13 Women Artists Featured at Hilles Library Dedication,” The Boston Globe, 8 February 1967, 58. George Aarons was a well-established New England sculptor. He divided his time between Brookline and Gloucester, in Massachusetts. He created the bust of Adlow in 1931, which now resides at the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- DAP; F. J. Wilkins to The Editor, Monitor, 2 April 1945, A-138, folder 15. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- DAP; Miss Royce Moch to Edith Palmer, Monitor, 27 October 1949, A-138, folder 5. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- DAP; Bert Hartrey and Elizabeth Balcom, “ Biography,” c. 1986, A-138, folder “Inventory.” Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- DAP; Erwin D. Canham, “Foreword,” A-138, folder 17. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- Electra Slonimsky Yourke, “Dorothy Adlow” in Dear Dorothy: Letters from Nicolas Slonimsky to Dorothy Adlow, edited by Electra Slonimsky Yourke, Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 15.

- See “Adlow Collection of Legal History,” Boston Public Library.

- Koussevitzky was conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1924 to 1949.

- Yourke, “Dorothy Adlow” in Dear Dorothy: Letters from Nicolas Slonimsky to Dorothy Adlow, 18.

- David Miller, “Modernist Music for Children: Three Sketches of Anton Webern in the Midcentury United States,” The Journal of Musicology, 37, no. 4 (Fall 2020), 496.

- Roderick Nordell, “‘Lexicon of Musical Invective’ Author Leaves Bright Legacy,” Monitor, 1 January 1996, 13.

- Adlow, “Dorothy Adlow: General Reflections, 1927.

- “Boris Mirski Gallery Records, circa 1936–2000, bulk 1945–1970,” Smithsonian, “Archives of American Art,” “Historical Note,” accessed 05 24 2024, https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/boris-mirski-gallery-records-9939/historical-note

- Alpha Gallery, “Hyman Bloom,” accessed 05 22 2024, https://www.alphagallery.com/artists#/hyman-bloom

- Canham, Commitment to Freedom, 354.

- DAP; Canham to Adlow, 1 March 1949, A-138, folder 5. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- Adlow, “Hyman Bloom’s Solo Exhibition: ‘Young Artist’s Work on View at Stuart Gallery,’” Monitor, 15 November 1945, 4.

- Bernard Chaet, “The Boston Expressionist School: A Painter’s Recollection of the Forties,” Archives of American Art Journal, 20, no. 1 (1980), 29.

- See “Art, ‘Judgment Day for Judges,’” Time, 19 March 1949.

- Ethel Bell to Christian Science Publishing Society, 24 March 1945, Church Archives, Box B20170, Folder F119843.

- Canham to Bell, 4 April 1945, Folder F119843.

- Memorandum from Canham to Mr. Jandron, 20 July 1950, Church Archives, Box B20775, Folder F119913.

- DAP; Bert Hartrey and Elizabeth Balcom, “ Biography,” c. 1986, A-138, folder “Inventory.” Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- Diggory Venn, “Division of Education & Public Relations, MFA, Boston,” Annual Report, 1964, 93–-94.

- Adlow, Monitor, 9 November 1954, 8.

- Adlow, “Blake’s Biblical Pictures: Symbolism Explained,” Monitor, 2 February 1959, 10.

- DAP; Mitchell Siporin to Dorothy Adlow, 28 January 1952, A-138, folder 14. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

- DAP; Erwin D. Canham, “Foreword,” Roads to Understanding Modern Art by Dorothy Adlow, edited by Frances Sharf Fink, unpublished manuscript, A-138, folder 17. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.