Women of History: Rachel Crane Mather

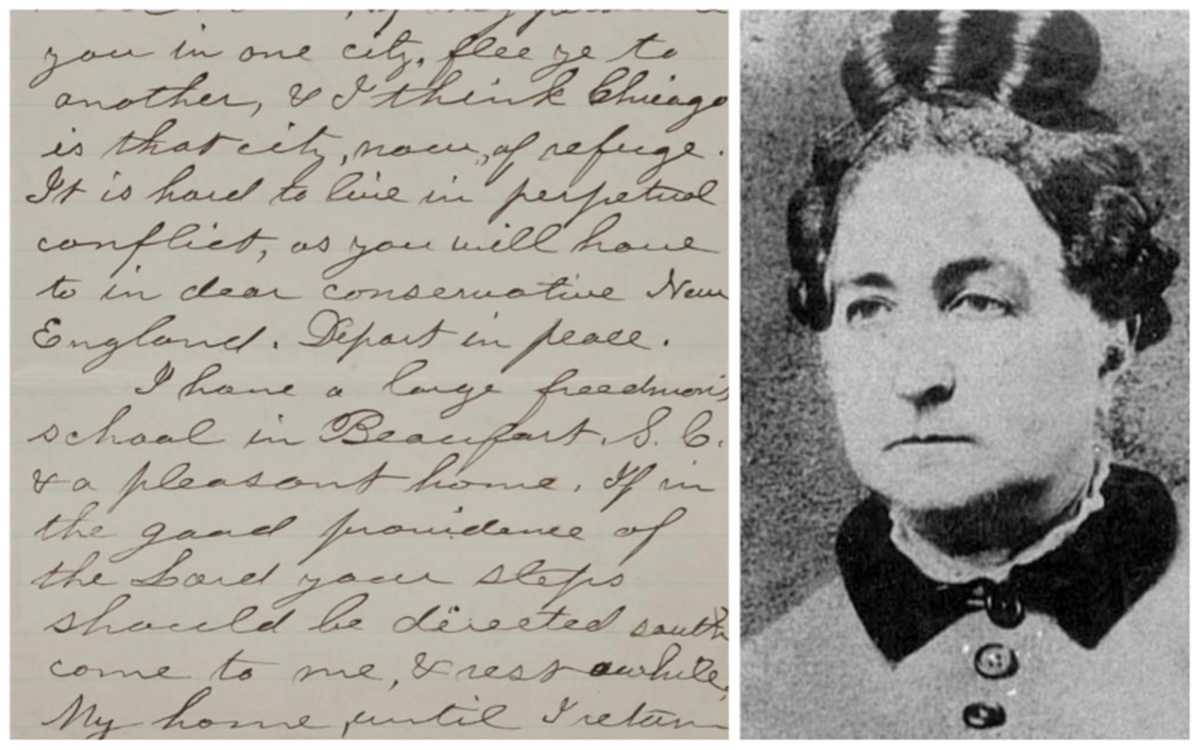

Rachel Crane Mather to Mary Baker Eddy, September 16, 1879, 593b.61.008. Photo of Mather courtesy of Beaufort County Library (South Carolina).

Listen to this article

While not well-known today, Rachel Crane Mather (1823–1903) was a pioneer in bringing education and opportunity to African Americans. Like Mary Baker Eddy, she found her life’s purpose in middle age and on her own. While the two women crossed paths only briefly, a letter in our collection indicates that their encounter was evidently quite meaningful to Mather.

She was born Rachel Rich in Troy, New Hampshire, where her father, Ezekiel Rich, was a Congregational minister. She became a teacher, although it is not known where she attended school. In 1846 she married Joseph Higgins Mather, Jr., a Baptist minister, in Providence, Rhode Island. He died of tuberculosis just five years later, and this was soon followed by the loss of their younger son, Samuel. At this point, Mather returned to teaching, at Bigelow School for Boys in Boston.

Soon after that, Mather moved to Beaufort, South Carolina, to train teachers at a “normal school” funded by the American Missionary Association (AMA), an organization established in 1846 and dedicated to providing African Americans and Native Americans with a liberal, Christian education. The AMA also supported charitable organizations and religious denominations that established schools for ex-slaves in the North. After the Civil War ended, these efforts spread to the South.1

Mather worked a year for the AMA. Then she left to establish her own boarding school, seeking to provide the food, clothes, and housing that she felt her pupils urgently needed in addition to education. And she was successful—within the year, she had purchased land and buildings for the Mather School, which opened in 1868. She taught “reading, grammar, and moral development” centered around Bible study, Sunday school, and prayer services, as well as domestic training (sewing, cooking, gardening, housecleaning, etc.).2

When Mather traveled north each summer to avoid South Carolina’s heat and mosquitoes, she used the time to promote her school and solicit donations in various forms, through her religious and philanthropic networks. This is how she met Mary Baker Eddy. (It is also possible that she had known of Eddy’s brief stay in the Carolinas in 1844, during her first marriage to George Washington Glover.) This excerpt from her letter to Eddy dated September 16, 1879, the day after their one visit, gives us some insight into their discussion:

My dear Mrs. Eddy,

Ever since my brief interview with you last P.M. I find that you linger in my heart. Indeed my mind seems in perpetual labor and travail to bring forth some good for you. But O how powerless to do, I am. Fain would I convey to you on paper this morning my warm sympathy and affection. Fain would I impart to you some support and benediction, while you walk through the furnace; but the Lord, I am sure, walks with you there, and no real evil can harm you. I hear a voice within saying to you, “Arise and shine, for thy light is come, and the glory of the Lord is risen upon thee.” As you kindly say to me, “Ignore pain and lameness,” so would I say to you, ignore opposition and persecution as much as possible. Every truth-bearer to this sick, sinning world must weep and pray at Gethsemane, shoulder the cross, and pass on to Calvary, immolate self, and there abide a living holocaust, till He who is the resurrection and the life bids thee, “Arise and shine.” …

I have a large freedman’s school in Beaufort, S.C. and a pleasant home. If in the good providence of the Lord your steps should be directed south come to me, and rest awhile….3

Around 1890 Mather transferred ownership of her school to the Woman’s American Baptist Home Mission Society. She continued her connection with the school and its mission until her death. The Mather School, well-known for its efforts to support the education of African Americans during an era of widespread racial segregation, operated until 1968, when as Mather Junior College it merged with Benedict College of Columbia, South Carolina.

Mather is also known for assisting in relief efforts after the Great Sea Island hurricane of 1893. In addition to distributing supplies, she wrote letters and published notices in newspapers that gained awareness of the devastation the storm had caused. Her efforts raised the equivalent of about $163,000 in today’s dollars to aid those left homeless.4

Listen to Women of History from the Mary Baker Eddy Library Archives, a Seekers and Scholars podcast episode featuring Library staffers Steve Graham and Dorothy Rivera.

- Hahn, Steven, A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South From Slavery to the Great Migration (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003), 276–277.

- Beasley, S.F. (2014). Pioneering Women of Southern Education: A Comparative Study of Northern and Southern School Founders. (Doctoral Dissertation), 82, 92, 95. Retrieved from http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2781

- Rachel Crane Mather to Mary Baker Eddy, 16 September 1879, 593b.61.008.

- For more on this, see Mather, Rachel Crane, The Storm Swept Coast of South Carolina (Woonsocket, Rhode Island: Charles E. Cook,1894), http://lcdl.library.cofc.edu/lcdl/catalog/lcdl:87347