Suffrage activist Matilda Hindman, who corresponded with Mary Baker Eddy

in 1876. Courtesy of the University of Mount Union Library.

On October 26, 1876, Matilda Hindman (c.1828–1905) replied to a note from Mary Baker Eddy (then Mary Baker Glover), written three days earlier. Although Eddy’s letter is not extant, and Hindman’s letter seems rather slim at first glance, their exchange provides strong evidence of Eddy’s early support of women’s rights.

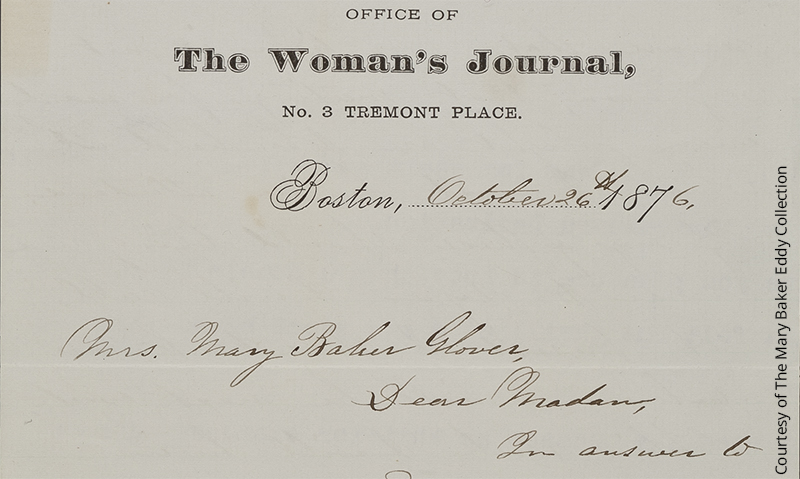

Writing on the office stationery of The Woman’s Journal (1870–1931)—a weekly women’s rights newspaper published every Saturday in Boston and Chicago—Hindman states:

In answer to your note of the 23rd permit me to say I was indeed very glad to hear that you not only approve of the principles you heard discussed in Lynn the 19th inst. but that you are willing to work for their advancement.1

Matilda Hindman wrote to Mary Baker Eddy (then Mary Baker Glover)

on the stationery of the office of The Woman’s Journal (593A.61.043).

Apparently Mary Baker Eddy had recently attended an informational meeting in Lynn, Massachusetts, about women’s suffrage activities. 2 A renowned public speaker, prominent suffragist, and writer, Hindman lectured on suffrage all over the United States and had spoken in Lynn a week earlier. Originally from Union Township in Washington County, Pennsylvania, Hindman was one of the first women to receive a Bachelor of Arts degree from a U.S. college, when she graduated in 1860 from Mount Union College in Alliance, Ohio. She would later return there for a time, to teach mathematics. Much about Hindman’s suffrage career can be learned from History of Woman Suffrage, edited by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage, as Hindman was active in both the National Woman Suffrage Association and the American Woman Suffrage Association. Here we read an account of her public speaking on suffrage and other women’s rights:

Matilda Hindman, representing Alleghany county, evinced both energy and enterprise in forwarding the movement through the agency of public meetings. She did good service from the beginning, relying almost solely upon her own determined purpose. Her deep interest in the work and its object, and the courage that animated her at the first impulse of duty, have continued without abatement to the present time. Her usefulness and activity have not confined themselves within the limits of Pennsylvania but have extended to other States both in the East and West.3

Hindman’s parents were activists in their own right, setting the model for their daughter. Both campaigned strongly in the late 1830s and early 1840s for equal pay for the women who taught in their local school. They felt that the women who taught in the summer should be paid the same as the men who taught in the winter. They secured equal pay for the women and restored it when it was later revoked.4

In her efforts to secure the right to vote for women, Hindman placed special emphasis on working with Christian churches, where she found willing audiences already active in social justice issues including poverty and temperance. Many suffragists considered such on-the-ground efforts missionary work and viewed equal rights for women as a deeply moral cause.

It is unclear whether Hindman had heard of Eddy and her work as the leader of the fledgling Christian Science movement prior to receiving her letter, but she could have read of Eddy’s concern for the rights of women in her textbook on Christian Science, Science and Health, first published the previous year in October 1875. Here Eddy acknowledged the legal peril women faced in basic rights, property ownership, and parental control of their children—issues Eddy herself dealt with after her first husband died, when her son was later taken from her, and when her second husband deserted her. She wrote:

The rights of woman are discussed on grounds that seem to us not the most important. Law establishes a very unnatural difference between the rights of the two sexes; but science furnishes no precedent for such injustice, and civilization brings, in some measure, its mitigation, therefore it is a marvel that society should accord her less than either. Our laws are not impartial, to say the least, relative to the person, property, and parental claims of the two sexes; and if the elective enfranchisement of woman would remedy this evil without incurring difficulties of greater magnitude, we hope it will be effected. A very tenable means at present, is to improve society in general, and achieve a nobler manhood to frame our laws. If a dissolute husband deserts his wife, it should not follow that the wronged and perchance impoverished woman cannot collect her own wages, or enter into agreements, hold real estate, deposit funds, or surely claim her own offspring free from his right of interference. A want of reciprocity in society is a great want that the selfishness of the world has occasioned.5

In her letter to Hindman, Eddy also apparently invited the suffrage activist to call on her at her home at 8 Broad Street in Lynn. Hindman responded that her time was not her own and she had speaking engagements arranged for most every night: “If any of these should bring me near to Lynn I will call. At present I do not know where I will be next week.”6

Although Eddy’s contact with Hindman was brief, it was not her first or only contact with leaders of the women’s rights movement. Prior to Hindman’s lecture, Eddy had attended a debate on women’s rights featuring suffrage leader Mary A. Livermore, in November 1871. Although originally not sure the topic interested her much, Eddy was evidently persuaded by Livermore’s arguments, for soon after the lecture she joined the Massachusetts branch of the American Woman Suffrage Association, paying her initial membership dues to Livermore herself. Over the years, Eddy and Livermore exchanged a few letters, and in 1899 Eddy sent her an inscribed copy of her book Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896.7

We have no further correspondence between Matilda Hindman and Mary Baker Eddy in our archive, but it is interesting to note that the above passage about equal rights published in the first edition of Science and Health remained almost verbatim through the final edition, published 35 years later.

To read Matilda Hindman’s letter to Mary Baker Eddy, go the Mary Baker Eddy Papers and select document 593A.61.043.

- Matilda Hindman to Mary Baker Eddy, 26 October 1876, 593A.61.043.

- Women’s suffrage was a movement that advocated for women’s right to vote and to run for elective office.

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan Brownell Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage, eds., History of Woman Suffrage (Rochester, NY: Susan B. Anthony, 1886), 3:458.

- Ibid., 458-459.

- Mary Baker Eddy, Science and Health (Boston: Christian Scientist Publishing Company, 1875), 322.

- Hindman to Eddy, 26 October 1876, 593A.61.043.

- Sherry Darling and Janell Fiarman, “Mary Baker Eddy, Mary A. Livermore, and Woman Suffrage,” The Magazine of The Mary Baker Eddy Library for the Betterment of Humanity, (Fall 2004), 10-17.