From the Collections: A rich portrait of Bicknell Young

Portrait of Bicknell Young, c. 1930. Courtesy of Longyear Museum.

The history of the Christian Science church includes a host of fascinating stories—some unexpected. Such is the case with Bicknell Young (1856–1938), a noted Christian Science practitioner, teacher, and lecturer. While his name might be familiar to many, his connection to Brigham Young (1801–1877), the nineteenth-century leader of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also known as the Mormon Church), might be surprising. Here’s what some of the research in our collections has revealed.

Family background and early life

Brigham Bicknell Young was a nephew of the Mormon leader Brigham Young. In fact, he was named after this uncle. His father, Joseph Young (1797–1881), was Brigham’s older brother. His mother, Jane Adeline Bicknell Young (1814–1913), was also a pioneer Mormon and eyewitness to her church’s early history. Bicknell was born into a prominent polygamous family; Joseph had four wives when Bicknell was born and later added a fifth, which accorded with Mormon teachings of that era. Jane was Joseph’s first and only legal wife and the mother of ten children, of whom Bicknell was the youngest; he was the seventeenth of 21 children whom Joseph fathered.1

Bicknell—called “Brigy” and “B.B.” by his family—grew up in Salt Lake City, Utah Territory.2 The United States Census of 1870 lists him as attending school at age 14 and living with his father, mother, and five sisters.3 Documents of April 18, 1868, from the Salt Lake City Thirteenth Ward Relief Society, noted this about the Thirteenth Ward, where the Youngs lived:

[It] occupied nine blocks in the heart of Salt Lake City adjacent to Brigham Young’s office and family residence. This congregation [wards functioned both as church and political divisions], the largest in Salt Lake City, included many prominent church and civic leaders ….”4

Historical sources note that Joseph was well-known for his “sweet singing of Wesleyan hymns” and was “passionately fond of music.”5 So it’s not surprising that Bicknell studied both voice and piano, developing into a gifted baritone singer. He became recognized for his talent and even received instruction from a teacher who had trained at London’s Royal College of Music. Perhaps this motivated a bold venture; in 1879, at age 22, Bicknell traveled alone to London, with a letter of recommendation that gained him admission to the National Training School for Music.6 After that he attended the Royal College of Music, receiving a scholarship in his second year that likely made his continued studies possible.7 While Bicknell was so far from home in England, his father worried about his moral welfare—and, in fact, his son did apparently distance himself from religion while there.8 A later biographical sketch by Christian Scientist William D. McCrackan confirms this:

…he had drawn away from the family faith in youth and had gone out into the world to struggle for an artistic career against great odds and amidst great hardships…. He spoke to me occasionally of his long contest with poverty … when he was trying to get a foothold in the musical world in London.9

A marriage, a musical career, and a healing

During his studies, Bicknell met Elisa Mazzucato (1846–1937), a talented musician and one of the teachers at the Royal College described as “a lady of great sweetness of disposition.” They were married in 1883. A native of Milan, she has her own significant story to tell, both as an accomplished musician and Christian Scientist (look for an article on Elisa next month in our “Women of History” series).

Family portrait of Bicknell Young and Elisa M. Young with their three sons, c. 1900. Courtesy of Longyear Museum.

In their first four years of marriage, Elisa and Bicknell had three sons: Arrigo, Hilgard, and Umberto. The family moved from England to Salt Lake City in 1885, where they performed and opened a music school. From 1888 to 1890 they lived in Omaha, Nebraska. By 1890 they had moved again, permanently relocating in the fast-growing city of Chicago, to pursue their musical careers.10 An 1891 recital program lists Bicknell on the faculty of the National School and College of Music, performing “Song of the Morn” accompanied by “Mme. Mazzucato-Young.”11

That performance marked an important turning point in Bicknell’s spiritual and religious life. Over the previous year he had been ill—and perhaps discouraged. One of his sons later wrote that his father had been an agnostic at that time.12 But, as a later account states, Bicknell was “healed in 1890 of serious physical diseases by Christian Science.”13 According to McCrackan, this healing held an additional benefit. He recalled that Bicknell “never mentioned his trials to me without referring at the same time to his gratitude to Christian Science for having rescued him from the pressure of want and the fear of poverty.”14

A change of direction

Bicknell and Elisa Young joined The Mother Church (The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston) in December 1894. During this time a great spiritual stir was occurring in Bicknell’s family. Its members were becoming Christian Scientists. While this may have been due to the influence of Bicknell and Elisa, it was also true that the religion was gaining a foothold in Utah.

We can’t know for sure how the rest of the Young family responded to the change of faith that was taking place. But we have letters that give some indication. “There has been for several years growing up in our midst,” noted Seymour B. Young, one of Bicknell’s older brothers, “a silly system of faith designated Christian Science …. Mrs. Kilt [sic] Haywood Kimball became one of [Mary Baker Eddy’s] leading disciples and she also converted my mother and all my sisters and B.B. Young our youngest brother….”15 Neither do we know Bicknell’s feelings about his Mormon background. The fact is, he never publicly or privately commented on his childhood religion. His son Hilgard knew this from experience:

In his early boyhood and for reasons of his own, Bicknell Young separated himself from the Mormon Church. This was an emphatic and unequivocal stand on his part. Thereafter, when he was married and the father of growing sons, we learned, without asking, that the Mormon Church was not a topic for conversation, and in all the years, that rule was followed.16

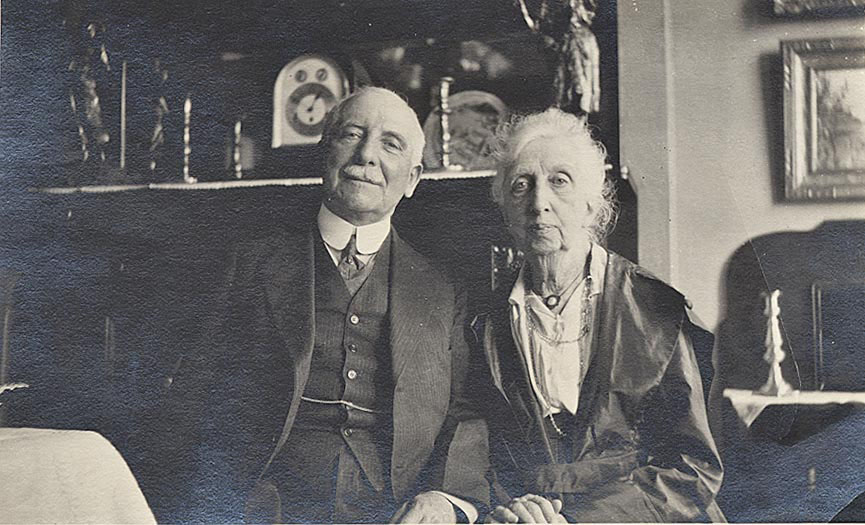

Portrait of Bicknell Young and Elisa M. Young, c. 1930. Courtesy of Longyear Museum.

A life of service to Christian Science

Edward A. Kimball, CSD, instructed both Bicknell and Elisa Young in practicing and teaching Christian Science, first in his 1895 Primary class and then in his 1901 Normal class. Bicknell’s sister Vilate also studied with him. Kimball wrote to Eddy that Bicknell was “one of the best students of the second generation [of Christian Scientists] that I know of.” In turn, Bicknell greatly admired Kimball, whom he had first met in late 1891.17

Bicknell entered the public practice of Christian Science healing around the turn of the century, his name first appearing in the directory of The Christian Science Journal in April 1900. This was a decade after his initial healing. Elisa was listed as a practitioner from 1904 to 1910. For a time they shared an office at 243 Wabash Avenue in the Chicago Loop. They were early members of First Church of Christ, Scientist, Chicago, where Bicknell was soloist. From 1898 to 1902, Bicknell was First Reader at Second Church of Christ, Scientist, Chicago, which he and Elisa helped to found.18 He also served for a year as the Christian Science Committee on Publication for the state of Illinois.19

A masterful lecturer

In 1903 he was appointed to the Christian Science Board of Lectureship—the role for which he became best known. He wrote to Eddy of his appointment:

I desire in this work and in all ways to be useful to our Cause, the Cause of God on earth, which you have so grandly and so nobly established through untold labor and self-sacrifice and which your inspired teachings show must be maintained through loving humility and righteousness on the part of those who have named the name of Christian Science.20

He was a Christian Science lecturer for most of the period from 1903 until 1938, and made the first round-the-world lecture tour by a member of the lecture board.21 He broke once to fill a three-year term as First Reader of The Mother Church, from 1917 to 1920, and another time to take a sabbatical for prayerful study and practice, from 1927 to 1931. From 1911 to 1917, he was also that board’s chairman.22 In 1904 Eddy’s secretary George Kinter wrote to him on her behalf: “She also directs me to say to you that she has had much pleasure in reading your lectures, and finds them very satisfying.”23 This may have been why Eddy had selected him to read her message at the dedication of the Christian Science church in Concord, New Hampshire, that summer.24 In the fall of that year, she wrote to him herself, after reading the text of his lecture, calling it “wise, eloquent, convincing, inspiring.”25

Our collections include a handful of additional letters he wrote to Eddy. One, written aboard a transatlantic liner, refers to his experiences lecturing in Europe:

In Great Britain and Ireland and also in Berlin, Germany, the most noticeable feature at the lectures was the deep interest which the public manifested in hearing of you. You have taught us how to understand and practise the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the Gospel of Love, but the whole world is feeling the regenerative and healing influence of your teaching. The attitude of loving interest displayed by the public at the lectures proves that the gratitude and love which Christian Scientists feel towards you is extending over the whole world.

We are just nearing New York ….26

Eddy replied a few weeks later:

Your dear letter of the 22nd ult. came duly. This is my first chance to reply. Your comments on the receptivity of Great Britain, Ireland, and Berlin, Germany, were deeply interesting. You thought of me on the sea; I think of you as attempting to walk over the waves that I have walked — and not fearing but rising on every billow. God bless you, and reward your eloquent and deep felt appeals in behalf of Christian Science, as He is doing.

Lovingly yours,

Mary Baker Eddy27

Why was Bicknell Young regarded as such an effective lecturer? “Young had not the native humor and wit of [Edward] Kimball,” McCrackan wrote candidly, “nor his faculty for springing a joke on the audience at a tense moment when its receptivity to the deep things of metaphysics was stretched to the breaking point, but Young brought to his work much polished culture, a generous vocabulary, and a pleasing presence.”28 But McCrackan went on to explain that there was more to it than just that:

I can…speak about his lecturing from having listened to him many a time and marvelled at the superlative handling of his subject. Young, more than any other lecturer, continued Kimball’s method and manner of unfolding his subject, step by step and stage by stage, so as to cover the whole ground, to establish the whole truth and sweep the stage clear of every obstruction or error…. [H]e continued to give the impression of spontaneity in his lectures which was so attractive and powerful a feature of Kimball’s lectures…. This was true healing work. Kimball and Young both understood that a Christian Science lecture ought not to be a lecture about Christian Science, but ought to be Christian Science itself, uttered and demonstrated.29

As a teacher of Christian Science, he held most of his Primary classes in Chicago. Notably, his mother was in his 1903 class.30 From 1909 to 1913 he and Elisa again lived in England, at the request of the Christian Science Board of Directors. He practiced and taught Christian Science there, and also lectured in Europe.31 He instructed new teachers of Christian Science twice, presiding over Normal classes for the Church’s Board of Education in 1910 and 1937.32

He contributed one article to the Christian Science periodicals, titled “Prophecy.” It appeared in The Christian Science Journal in 1919.33 Several of his early lectures were reprinted in the Christian Science magazines, or as pamphlets. He could write fluently, as seen in his reprinted letters to Eddy and to the press.34 The Mary Baker Eddy Library’s Published Lecture Collection includes some of these lectures, which are available on request. A number of unauthenticated works attributed to Young have been in circulation over many decades.

Bicknell Young passed away in Carmel, California, on March 5, 1938.35 He and his wife, Elisa Mazzucato Young, are noteworthy figures in the history of Christian Science, especially because of their devotion to its practice. He pointed succinctly to the naturalness of such commitment in a 1922 lecture: “Living the Christ-life involves us in the acceptance and practice of the Christ-healing.”36

For more related content, read the article Women of History: Elisa Mazzucato Young and listen to the Seekers and Scholars podcast episode Bicknell Young—a Mormon and Christian Science story.

- “Brigham Bicknell Young,” Ancestry.com, accessed 10/7/2021.

- Utah was a United States territory from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when it was admitted to the Union as the 45th state.

- Polygamous husbands sometimes resided primarily with one wife and visited their other wives and children.

- “Salt Lake City Thirteenth Ward Relief Society, Minutes, April 18, 1868,” in The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women’s History (Salt Lake City: The Church Historian’s Press, 2016) 3.7, accessed 10/29/2021,https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/church-historians-press/the-first-fifty-years-of-relief-society/part-3/3-7?lang=eng

- Kenneth L. Cannon II, “Brigham Bicknell Young: Musical Christian Scientist,” Utah Historical Quarterly, Spring 1982, 125.

- Cannon, “Brigham Bicknell Young,” 125.

- Edward Williams Tullidge, “The History of Salt Lake City and Its Founders,” in Tullidge’s Histories, vol. II (Altenmunster, Germany: Jazzybee Verlag, 2019), Ch. LXXXVI.

- Cannon, “Brigham Bicknell Young,” 130.

- William D. McCrackan, “Bicknell Young,” n.d., 2, Subject File, Young, Bicknell.

- See Cannon, “Brigham Bicknell Young,” 127-129. (Coincidentally, this was the year the Mormon Church renounced polygamy, under intense pressure from the United States government.)

- “National School and College of Music, Fourth Recital,” c. March 1891, Subject File, Kimball, Edna (Wait).

- Hilgard B. Young to Leonard J. Arrington, 26 July 1967, cited in Cannon, “Brigham Bicknell Young,” 130.

- “International Board of Lectureship of The Mother Church of Christian Science,” 1905, Subject File, Young, Bicknell.

- McCrackan, “Bicknell Young,” 2.

- Seymour B. Young, Journal, 21 June 1896, LDS Archives, quoted in Jeffery O. Johnson, “The Kimballs and the Youngs in Utah’s Early Christian Science Movement,” unpublished paper, n.d., Subject File, Johnson, Jeffery O., 7. Seymour Young and LeGrande Young, Bicknell’s full brothers, were important figures in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

- Hilgard Young to Anne Holliday Webb, 13 May 1971, Longyear Museum Collection.

- Edward A. Kimball to Mary Baker Eddy, 1 July 1901, IC155dP2.25.009. For Young’s estimate of Kimball, see Young, “Personal Recollections,” in Lectures and Articles on Christian Science by Edward A. Kimball, ed. Edna Kimball Wait (Chesterton, IN: H. H. Wait, 1921), 11–13, and letter from Young to “Beloved friends [members of Eddy household at Chestnut Hill],” 18 August 1909, Subject File, Young, Bicknell.

- “Record of B.Y. activities in the Church,” n.d., Longyear Museum Collection.

- “International Board of Lectureship of The Mother Church of Christian Science.” He first came into contact with McCrackan, who served as Committee on Publication for New York, at this time.

- Bicknell Young to Mary Baker Eddy, 16 July 1903, 341.46.002.

- Anne Holliday Webb, “Bicknell Young, C.S.B.,” Longyear Quarterly News, Summer 1971, 120 https://www.longyear.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/LY_1971_Vol_8_No_2_Summer_QN.pdf

- Bicknell Young’s term as Reader concluded during litigation between the Christian Science Board of Directors and the Trustees of The Christian Science Publishing Society. He responded to rumors that he was critical of the Directors in a forceful letter to “Fellow Students and Co-workers in Christian Science,” 19 February 1921, LSC017; “Chairmen and Secretaries of the Board of Lectureship,” n.d., Subject File, The First Church of Christ, Scientist – Lectures and Board of Lectureship – Historical Record.

- George H. Kinter to Bicknell Young, 8 July 1904, L14099.

- The address, “Message on the Occasion of the Dedication of Mrs. Eddy’s Gift, July 17, 1904,” is found in Eddy’s The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 159–163.

- Eddy to Young, 15 October 1904, L10147.

- Young to Eddy, 22 December 1905, IC341.46.012.

- Eddy to Young, 12 January 1906, L10148.

- “Young was distinctively dapper in appearance…. Though a man of small stature he bore himself with great dignity…” McCrackan, “Bicknell Young,” 2.

- McCrackan, “Bicknell Young,” 1–2.

- Webb, “Bicknell Young, C.S.B.,” 120.

- John V. Dittemore/The Christian Science Board of Directors to Mary Baker Eddy, 9 September 1909, L00623.

- These classes continue to be held triennially and qualify experienced practitioners to be teachers of Christian Science. Teachers may annually instruct one class and organize their pupils into groups known as associations.

- Bicknell Young, “Prophecy,” The Christian Science Journal, June 1919, 111–115.

- On jshonline.com, search as keywords “Bicknell Young.”

- The New York Times, 9 March 1938, 23.

- Bicknell Young, “Christian Science: The Science of Life,” Published Lecture Collection, Church Archives, Box 530776, Folder 523334.