From the Collections: The Monitor takes flight

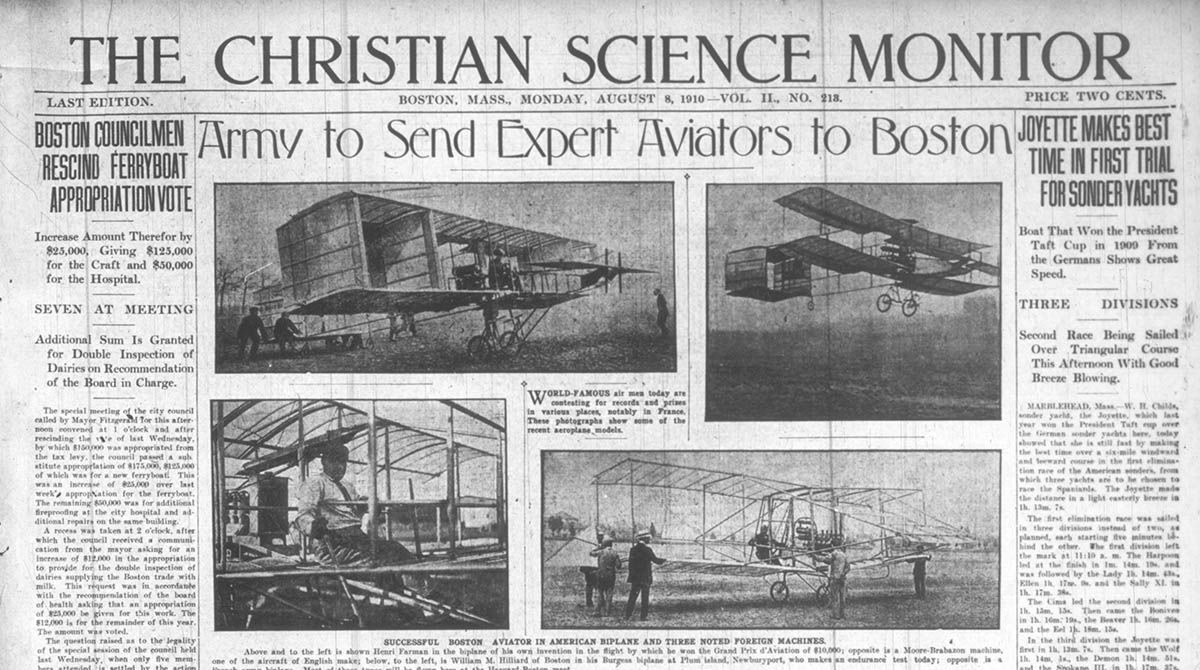

This front-page spread shows the Monitor’s coverage of the Harvard-Boston Aero Meet

—a historic event in the story of aviation. Courtesy of The Christian Science Monitor.

Our Library archives house issues of The Christian Science Monitor dating back to 1908, the year Mary Baker Eddy established it as an international newspaper. Looking through the headlines of the past can provide insight into people’s lives. What did they find important, interesting, challenging, or hopeful enough to put on the front page?

One subject that captivated reporters and readers alike was human-powered flight. The Monitor covered the growth and development of aviation extensively throughout the twentieth century. Early stories provide a glimpse into how that growth was beginning during the paper’s first days.

On December 19, 1908, the Monitor included a story titled “U.S. Aeroplanist Breaks Record.” It detailed the continuing accomplishments of pioneer aviator Wilbur Wright (1867–1912):

LE MANS, France – Wilbur Wright, the American aeroplanist, created a new world’s record for heavier than air machines while trying for the Michelin cup, remaining in the air 1h. 53m. 59s. The best previous record was 1h. 31m. 51s., which Mr. Wright made Sept. 21….

Mr. Wright closed a triumphant day by achieving another record, flying to a height of 360 feet in a strong wind, and winning the Sarthe Aero Club’s prize for height. At first it was thought that the violence of the breeze would compel him to postpone his effort, but, undaunted, he launched his machine and circled around and around the field. When soaring at 90 feet a sudden gust of wind caught the aeroplane sidewise, causing it to plunge violently backward. The spectators were terrified, but Mr. Wright remained unperturbed and soon righted his craft….

The Aero Club gave a dinner for Mr. Wright in celebration of his double victory. The Michelin cup is to be awarded to the aviator who makes the longest aeroplane flight before Dec. 31, 1908….1

It had been five years since Wilbur Wright and his brother Orville first successfully tested flight in December 1903—and less than a month since the Monitor’s November 25, 1908, launch. In the following years, the headlines would frequently and prominently feature exciting stories of this nature, detailing the advancements and competitions rapidly developing in the fledgling world of aviation.

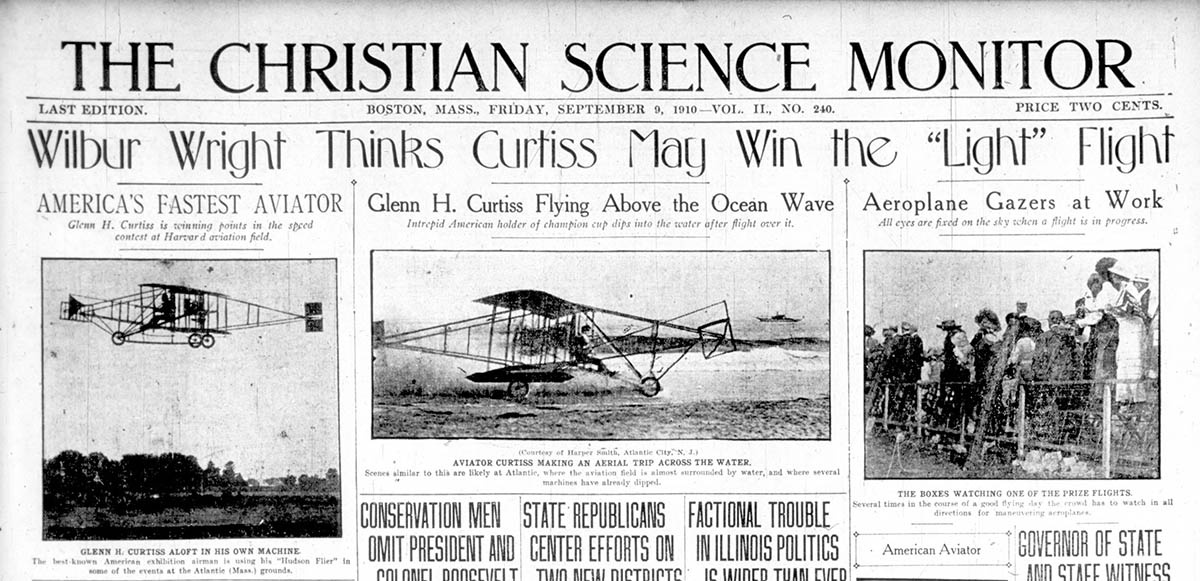

Headlines like this were common in the first decade of the Monitor’s life, and many

different names were highlighted. Courtesy The Christian Science Monitor.

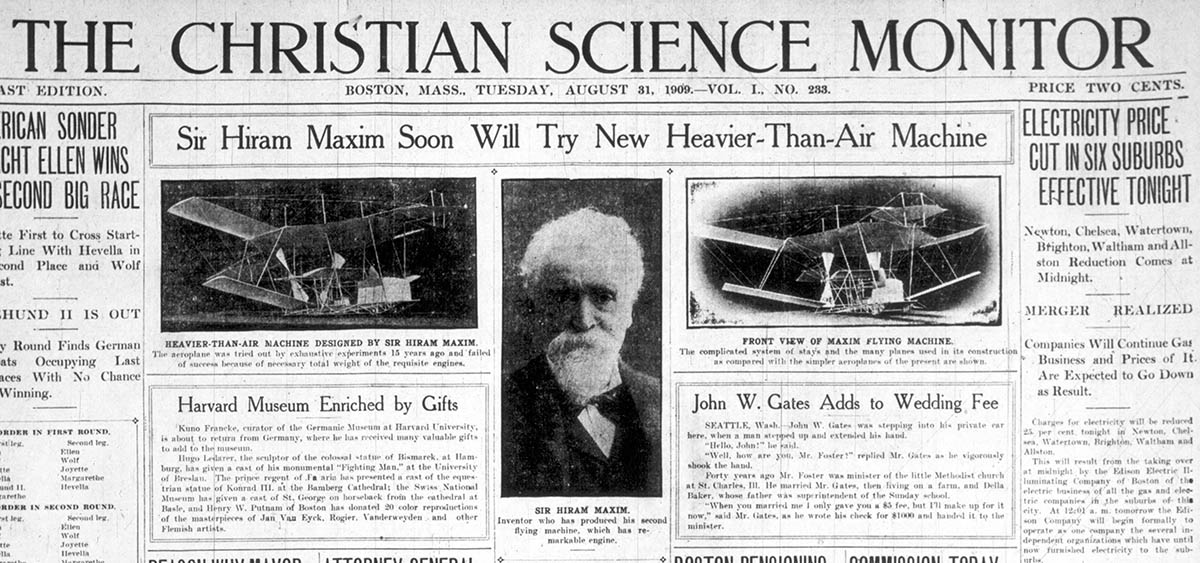

Another front page that prominently displays then-cutting edge machines, exemplifying the

sort of photographs that were attracting attention. Courtesy of The Christian Science Monitor.

In an unpublished retrospective on the history of the Monitor’s aviation coverage, staff writer and aviation editor Albert Hughes claimed that “aviation constitutes an essential means of communication, and, in the newspaper field where communication is important to the conduct of business, The Christian Science Monitor has ever been responsive to every phase of aviation.”2 Hughes asserted that the rise of the airplane contributed to more expedient news coverage “both through the speedy forwarding of dispatches by air mail and the transport of its correspondents by air to the far corners of the earth.” The impact of these developments on journalism in general—and the Monitor specifically—are profound. And the Monitor in turn has reported on aviation news throughout its existence. Hence the need for a dedicated aviation editor like Hughes and, for a time, a page devoted just to aviation news. Though the page itself only ran for a few years in the late 1920s, Hughes could boast a long and fruitful career covering aeronautical news.

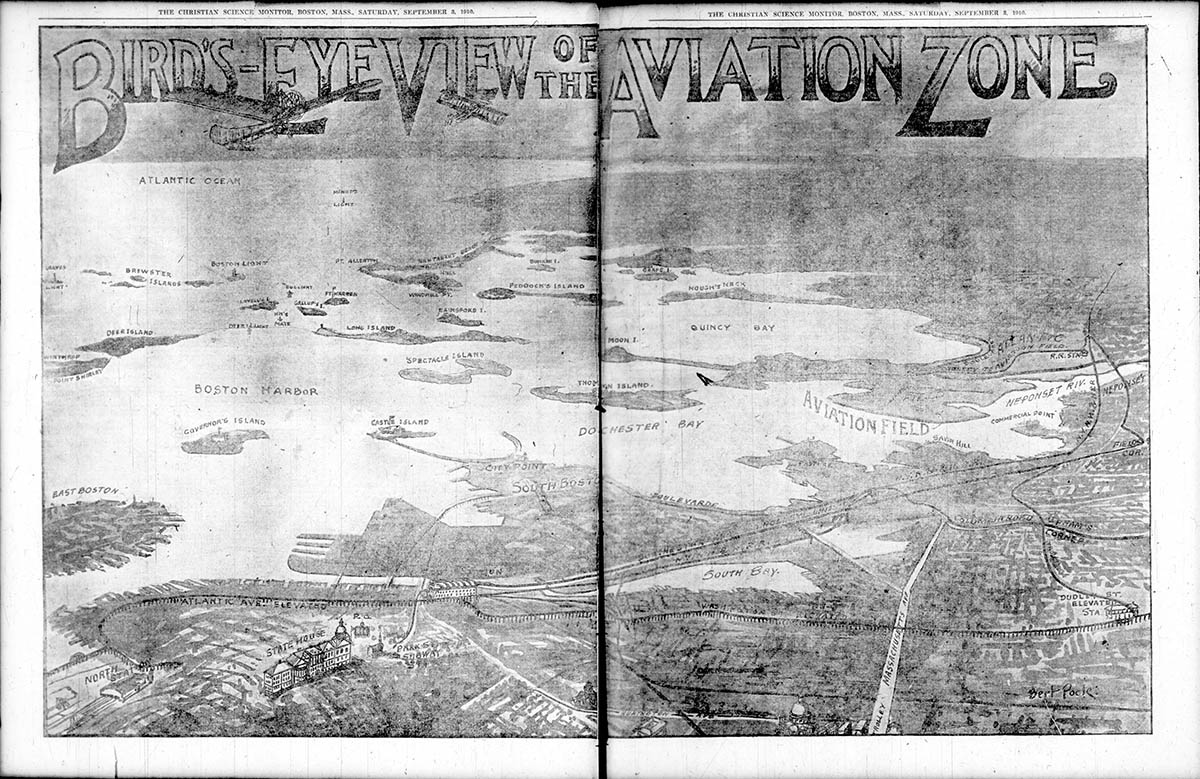

One early and significant event that the Monitor covered was the first Harvard-Boston Aero Meet. It took place early in September 1910, in Squantum, Massachusetts, south of Boston. Hughes called the event “the first and most important aeronautical meeting ever held in the northeastern section of the United States.”3 The meet spanned nearly two weeks and garnered extensive Monitor coverage, including daily front page stories, a two-page “bird’s eye view” map of the Boston area, and reports on notable American and international pilots who participated in the meet. During this time period, France and England were strong contenders in the race toward the sky. The British pilot Claude Grahame-White, a well-known flight pioneer in his home country, made a strong showing at the meet.

According to Albert Hughes, publishing a map such as this in a newspaper

was quite unorthodox for its day. Courtesy of The Christian Science Monitor.

A noted fan of Grahame-White herself, Eddy may have been among the enthusiasts for the Harvard Aero Meet, although she did not attend it. In his 1958 book Commitment to Freedom, Erwin D. Canham wrote that “she had a number of the members of her household go to the beach at Squantum, near Boston, where [Grahame-White’s] flight took place, in order to report to her in detail just what occurred.” Calvin Frye, Eddy’s personal assistant and a noted admirer of machinery, was one of them. In his 1932 reminiscence, Irving C. Tomlinson wrote that one day during the meet, Frye “hastily went into the house, changed his coat, jumped into the automobile and at two o’ clock was off for Squantum…. Mr. Frye returned home at five that afternoon. This was the longest vacation Mr. Frye had in all his years of service—certainly a mark of devotion.”4 While research indicates that Frye did, in fact, have other short periods of time off, there is no question that his work was tireless—and that he gave every indication of performing it in the spirit of willing commitment.

Eddy was enthusiastic enough about the event that her staff reportedly contacted Grahame-White and asked if he could attempt a flight over her Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, home. (He declined and kept to a relatively safe over-water flight.)5

This keen interest in aviation lines up with what we know about Eddy’s views on the immense technological progress she saw in her lifetime. New inventions, she said, “light the way to the Church of Christ. We use them, we make them our figures of speech. They are preparing the way for us.”6 From her perspective, technological advancement could make new things possible, and in that way broaden the reach of her message. However she did not extend this idea freely to every new convenience. For example, while it does appear that the world of flight caught her attention, she preferred her horses to any automobile.7

Amid the excitement of humanity’s achieving the dream of flight, and along with all the other forms of progress at the time, loomed the shadow of World War I. That 1908 Monitor story about Wright’s record-breaking flight concluded by mentioning the progression of airship development in Berlin: “The designer [of a balloon model said to rival field leader Count Zeppelin] expects to be able to carry two tons of explosives in his craft besides other supplies—a statement [that] clearly indicates the military intent of the invention.”8 The military potential of aviation was no secret to inventors and pilots. The story pictured above also discussed the US Army’s presence at Boston’s air meets. Nonetheless, Wright, Grahame-White, and their rivals pushed their machines to new heights with a sense of sportsmanship and adventure. For all of the destructive potential that the “aeroplane” possessed, perhaps there remained a belief that its potential for a positive impact on the world was greater—even as a deterrent to conflict. An element of this perspective can be seen in the headline of the Monitor’s September 8, 1910, issue, published in the middle of the Boston flight meet:

Great Air Discovery by Grahame-White May End All War

… Chairman Charles J Glidden of the aviation contest committee, announced at noon today that Mr. Grahame-White had made a remarkable discovery in his altitude flight late yesterday afternoon, which may put an end to war for all time. Mr. Glidden is not at liberty to give any further information as to this, but says that toward the end of the meet all the professionals will ascend together to develop this discovery….9

In retrospect we know that optimism was unfounded; at that point in time, humanity was approaching two unimaginable wars within a generation. The airplane did not serve as a deterrent to conflict—although it did give hope to people and has served many useful purposes in the decades since. The Monitor, for its part, lived up to its motto “to injure no man but to bless all mankind,” giving this mysterious and optimistic statement the front page treatment. When Eddy passed away only a few months after that historic air meet in Squantum, the newspaper that she founded was offering her followers hope that humankind’s ingenuity could make the future brighter.

Listen to “The Christian Science Monitor”—genesis and today, an episode in our Seekers and Scholars podcast series featuring a conversation with Editor Mark Sappenfield.

This article is also available on our French, German, and Spanish websites.

- “U.S. Aeroplanist Breaks Record,” The Christian Science Monitor, 19 December 1908, 5.

- Albert Hughes, “The Christian Science Monitor in Aviation,” circa 1953, 1. Church Archives, Box 20221, Folder 124564.

- Hughes, “The Christian Science Monitor in Aviation,” 4.

- Irving Tomlinson, “Mary Baker Eddy: The Woman and the Revelator,” 12 May 1932, Reminiscence, 650.

- Erwin D. Canham, Commitment to Freedom (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1958), 12.

- Mary Baker Eddy, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 345. Eddy stated this in a 1901 interview with the New York Herald.

- Irving C. Tomlinson, Twelve Years with Mary Baker Eddy, Amplified Edition (Boston: The Christian Science Publishing Society, 1994), 221.

- “U.S. Aeroplanist Breaks Record,” Monitor, 5.

- “Great Air Discovery by Grahame-White May End All Wars,” Monitor, 8 September 1910, 1.