The Concord story

By Tom Fuller

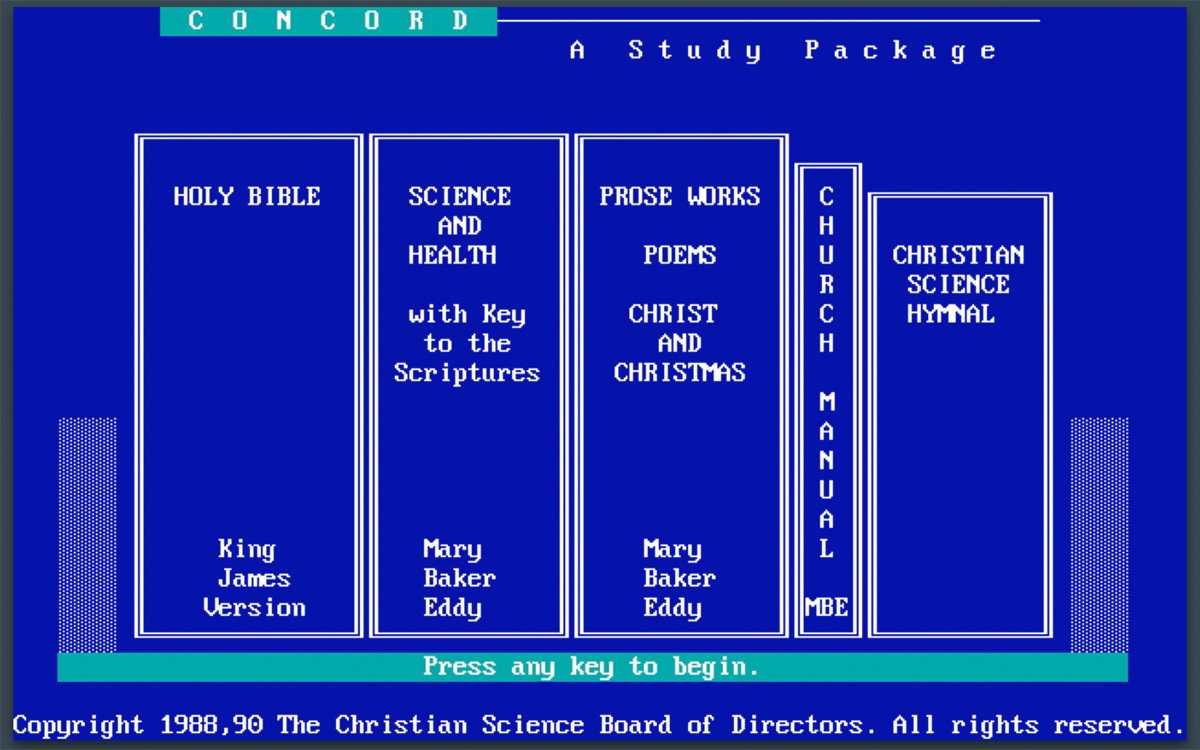

Welcome screen for the first version of the Concord software program. © The Christian Science Board of Directors.

“The use of words in the search for ideas is as ancient as language,” declared the first user manual for Concord, A Study Package in 1988. Paraphrasing Goethe, it went on, “When the mind is adrift in a sea of ideas, a word becomes a raft.”

Known today as Concord: A Christian Science Study Resource, this computer program is published by The First Church of Christ, Scientist (The Mother Church). It allows users to search the text of the Bible (King James Version), the writings of Mary Baker Eddy, and the Christian Science Hymnal. It also stores and prints textual excerpts, references, and notes. This article examines the 35-year history of five Concord versions. It also explores the software’s religious and historical context.

Words matter!

Among several things that made the ancient Hebrew religion remarkable among its Iron Age peers was monotheism. The one God was not to be worshiped through images. Instead, God was revealed to the people by divine actions (such as protection from enemy armies, plagues, and starvation) and by the written word: commands, laws, allegories, history, songs, wisdom, prophecies, and promises. Words outlasted the pagan idols, growing into the Bible and honored by its worshippers as the Word of God. Study of its roughly 783,000 evocative and 12,000 unique words—such as I AM, Spirit, Father, Christ, Jesus, salvation, science, error, dust—has rewarded readers with hope, insight, comfort, guidance, redemption, holiness, and healing.1

Words matter. The Scottish author Alexander Cruden (1699–1770) published a concordance to the King James Bible in 1737. According to the preface of one edition:

Hugo de S. Charo, a preaching Friar of the Dominican order…was the first who compiled a Concordance to the holy Scriptures: he died in the year 1262. He had studied the Bible very closely, and…employed five hundred Monks of his order to assist him. Many concordances followed the good Friar’s. Cruden concluded his own concordance’s preface with a prayer that God would render it “useful to those who seriously and carefully search the Scriptures.”2

Alexander Cruden, 1753. © Universal History Archive / Contributor / Universal Images Group / Getty Images.

In recent centuries, numerous concordances have facilitated Bible word search, including those by William Smith, Robert Young, and James Strong. They all help the searcher locate a word in its context, illuminating the message and providing further inspiration.

A unique opportunity

What does this mean in the context of Christian Science? Mary Baker Eddy ordained two books as pastor to The Church of Christ, Scientist: the Bible and Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures. Christian Scientists study them, regarding Science and Health as the key that unlocks the spirituality of the scriptures and presents the words and works of Jesus Christ as a healing Science. The Bible Lessons that form the basis of individual study are also read as the Sunday sermon in every Christian Science church.

The first Concord user manual stated that “the publishing of Mrs. Eddy’s works in a computerized format is a logical and natural extension of the continuing process of making her works available in different forms.”3 The Bible itself has assumed many forms during its history: scroll, codex, manuscript, and printed book. In the early 1970s, it was first published on the internet through an idle Sigma computer at the University of Illinois. Science and Health has similarly changed forms in its 150-year publishing history.4 It went through numerous editions, with both major and minor changes that Eddy made up until her passing in 1910. It was translated and published in German in 1912, and later in other languages including Braille (1924), on LP-records (1946), on audiocassettes (1970), and on DOS Concord computer diskettes (1988). This first version of Concord ran on personal computers, using Microsoft’s Disk Operating System (DOS).

Books intended for scholarly study typically include an index—a roadmap to their ideas. Rev. James Henry Wiggin (1836–1900) prepared the first index for Science and Health in its 16th edition, published in 1886. It was discontinued as part of a major revision in the 226th edition, as Eddy prepared for the publishing of the first concordance to her book in 1903,5 a task she assigned to Albert Conant, then organist of The Mother Church. Conant bought 12 copies of Science and Health and cut them apart into single pages glued to cardboard backings. He and his team sliced these into thousands of context lines. Conant put 6,000 hours (and much prayer) over 18 months into creating this concordance.6

James Henry Wiggin, n.d. P01807.

A distinctive element of Conant’s concordance was his effort to organize it beyond a simple word lookup; instead, he structured the book around major ideas and concepts. This can be seen in carefully selected entries where some references are arranged under headings related to the meaning of the word (see “I,” “Eddy,” “dates,” and any of the synonyms for God),7 as well as the extensive use of contextual subheadings for frequently referenced words. Cruden’s Concordance and Young’s Analytical Concordance to the Bible probably influenced his approach. Eddy reviewed draft versions of Conant’s concordance, endorsed it with a note to readers in the preface, and copyrighted it.

That’s the historical context. Now let’s examine three threads that converged in the mid-1980s to bring about DOS Concord: publishing methodology, computer technology, and the Christian Science community.

Publishing methodology

The printing and proofreading methodology of the early 1950s prompted a deep and lengthy analysis of the editions of Science and Health extant after Eddy’s passing.8 This resulted in the book’s 1970 Standard Edition (so named because of its textual and graphic fidelity). The Century Edition, published in 1975, marked the 100-year anniversary of the book’s first printing and incorporated a few graphical corrections, coinciding with the emergence of computer typesetting. After 13 proofreadings (forward and backward), the resulting computer tape became the basis for subsequent settings of Science and Health, including DOS Concord. Eddy’s other writings were similarly taken from computer typesetting tapes prepared by The Mother Church, which also purchased a computer tape of the King James Bible from the National Publishing Company in Philadelphia.

The only books by Eddy that required manual entry in order to be included in Concord were Poems and Christ and Christmas (the latter without accompanying illustrations). Both the words and music of the Christian Science Hymnal were manually entered and carefully verified. In the DOS version, only the hymn melody played. Macintosh Concord, which first appeared in 1991, played the full four-part harmony of the Hymnal’s 1932 edition, on any one of 12 instruments (my favorite is guitar!).

Computer technology

While printing achievements laid the groundwork for Concord, computer technology (the second thread) catapulted ahead. In a prescient 1972 memo, Publisher’s Agent Clem Collins envisioned an index to Eddy’s writings on a large computer at The Mother Church. Researchers (such as Christian Science teachers, practitioners, lecturers, and the Readers in churches) would access it, using terminals connected through home telephone lines. They would type in a query, transmit it to the Boston computer, and then receive a listing that contained relevant “context lines.” Selecting a particular context line, they could then request the text around it. Today, we take for granted the affordable speed of personal computers, phones, and watches. But in 1972 a computer that could store Eddy’s writings would have cost as much as a new house, and an access terminal (needed by each researcher) as much as a new car. Collins’ vision was certainly far-sighted, but the computers of that day were not up to it. During the next dozen years, computers advanced a thousandfold in performance per dollar. What was impossible in 1972 became eminently possible. The $3000 personal computer (PC) of the mid-1980s was more than sufficient to store and search these books (and without pricey long-distance calls to Boston). By the turn of the twenty-first century, I read the Bible and Science and Health on an Abacus watch!

The Christian Science community

The third thread in the development of Concord concerns the broadening vision of society in general, and Christian Scientists in particular. In 1971 an act of the US Congress extended the copyright of Science and Health in all editions for 75 years.9 However, in 1983 it was challenged and ultimately declared unconstitutional by a Federal Appellate Court in 1987.10 With that development, Science and Health returned to the public domain. Eddy had foreseen the time when her book would be out of copyright.11 At the same time, individuals were already experimenting with computerized versions of Science and Health. Some versions were scanned in, some were manually typed in by both laypeople and professional stenographers. Amid these multiplying efforts, the time was ripening for Concord to provide a uniform and professional means for accessing Eddy’s writings digitally.

The resulting stir was reminiscent of what had prompted the translation of Science and Health into German; while for some years there had been requests for a translation of the book, Eddy initially felt the time was not right. By March of 1910, German Christian Scientists were producing translations of the weekly Christian Science Bible Lessons in their own language. At that point, Eddy approved the creation of an authorized edition of the book in German (with facing pages in English), which took two years to produce.12 Similarly, faced with proliferating computer-based copies of Science and Health, The Mother Church needed to exercise (and safeguard) its role as the uniquely-authorized publisher of Eddy’s writings.

Concord conceived

The church had been wrestling with the idea of a computerized concordance since the early 1980s, as freelance versions cropped up among Christian Scientists. A couple of these early-version entrepreneurs were invited to The Christian Science Publishing Society and asked to “cease and desist” in distributing these versions. But they did not. Clearly a product from The Mother Church was urgently needed to provide an authorized, comprehensive digital reference tool.

But there were organizational complications to resolve. While Bibles and hymnals were published under the Publishing Society’s roof, Eddy’s writings (and most of the computer expertise) resided with the church. The project bumped between managers for a year or so. By 1986, a handful of computer pioneers (including me) came to work for the church in various technical and managerial positions. That June, three of us crafted a simple Concord demonstration (consisting of three simulated screenshots). I presented it to the Christian Science Board of Directors, who received it enthusiastically. However, not everyone was enthusiastic. In fact, a survey sent to Christian Science teachers and practitioners about a year earlier had found that 87 percent were opposed to the idea of Eddy’s works being published electronically. Further, the project would go nowhere until approved by the Trustees of the Publishing Society.

This was a yeasty time in the general publishing world, and particularly for the Publishing Society. During the years of DOS Concord’s development, the church published its first microfiche (a century of The Christian Science Journal and the Christian Science Sentinel); its first compact discs (compilations of hymns); its first video literature (presenting children’s Bible stories); and, at length, its first computer program (Concord). At the same time, the church was also moving into television and radio broadcasting.

A bold move

Concord was no snap decision. While it might seem harder to understand now, it was at the time a profound leap for those entrusted with publishing the books ordained as the church’s pastor—a leap that might shift how those seeking Christian Science related to it. One Publishing Society trustee questioned the manager of the General Publishing Group (GPG), who was presenting the Concord concept. “Does this mean that people will employ fewer bound books?” asked the trustee. “Yes,” the manager answered, “I expect it does mean that.” Each trustee took the proposal to his or her very heart. There were many days (and nights) of consecrated prayer devoted to making the decision—and later, in generous support of the project itself.

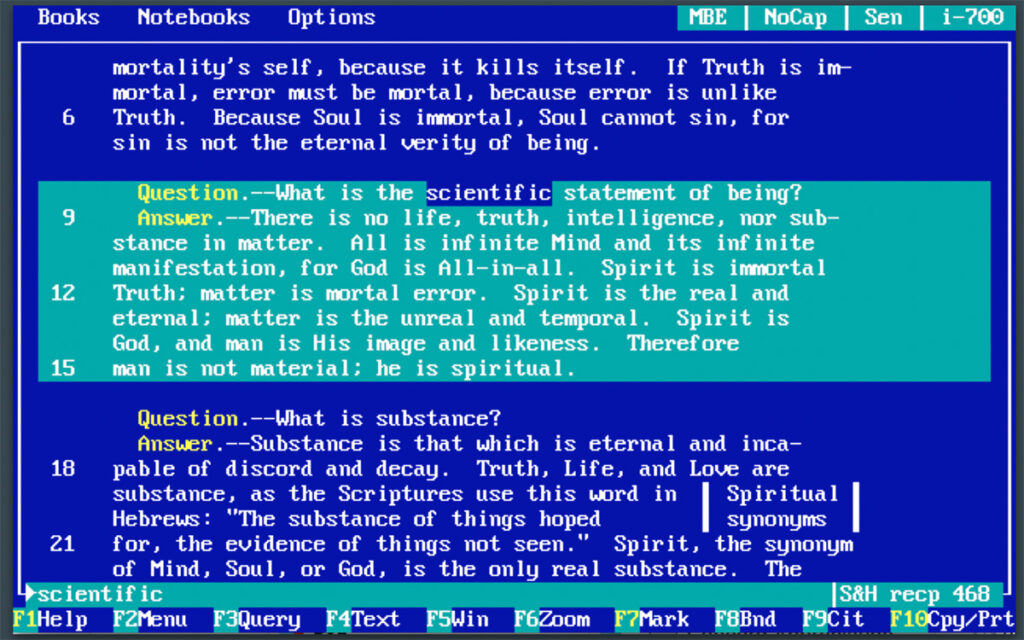

Page 468 of Mary Baker Eddy’s Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, visible in the first version of Concord. © The Christian Science Board of Directors.

In turn, the Board of Directors wrestled faithfully over their decision. When that GPG Manager presented the action memo for approval, one Director asked, “Do you foresee the day when Readers in churches will read from computers?” The manager responded, “Well, we don’t read from scrolls anymore.” That got a laugh. 13 After approving the project, the Directors were constantly solicitous, engaged, and earnestly supportive. Some served as alpha or beta testers. A year before Concord was ready for release, one director used a very primitive (and buggy) version of it to prepare an address. He thus became one of our alpha testers!

Once the project team had the go-ahead, it consulted six focus group panels across the United States that engaged expected users in wide-ranging conversations (including Christian Science practitioners, lecturers, teachers, branch church readers, Reading Room librarians, and contributors to the church’s periodicals). They identified probable uses, hopes and expectations, price points, areas of interest, and potential concerns. This informed Concord’s design, user manual, pricing, and advertising. Many of these users experimented with pre-release versions and contributed valuable feedback. I recall that one of the earliest alpha users was visually impaired and used a Versa-Braille console with her PC. She read the screen as Braille pins rose and fell on the console. She was radiantly grateful, as she now explored these loved books on her own, suddenly independent of outside aid.

Early on, the developing software was called the “Study Package.” In November 1987 a focus group was conducted in Elsah, Illinois, where Principia College is located. That evening, several members of the focus group and the project team sat around a table in the college pub. As darkness fell on the patio outside the floor-to-ceiling window, names were bandied about, debated, amended. During a pause, a retired English professor gently said, “Concord.” The pause lengthened. The debate was over. It was simply perfect—not just because of its consonance with the word concordance but also because a number of books and their indices were in fact blended concordantly into a unified software package.

Concord born

The development of Concord (using Turbo Pascal 4.0) constantly broke new ground. It faced many challenges common to any complex software program, but some were unique to its special office, purpose, and users. As the designers and programmers crafted the user experience (the text presentation, book panels, help screens, search aids, and other features that make using the program effective and enjoyable), they often returned to the theme that this software was a Christmas present to people around the world who studied Christian Science. Concord should sparkle in fidelity and friendliness—yes, a keen tool, but also a delight to use.

DOS Concord was The Mother Church’s first foray into publishing computer software. The team relied on the skills of dozens of employees, and a couple of contractors, to create the instruction manual, reference manual, reference card, packaging (originally containing 5.25-inch floppy disks), marketing materials, copyright notices, and announcements designed for Christian Science Reading Rooms. Each of these items had to be written, designed, and then produced in volume. It was a team effort in every sense of the word. We all grew. Years later, I join many who still recall this as the most inspiring and satisfying project of a career.

The team weighed the idea of augmenting Concord with other study resources: dictionary, thesaurus, other Bible translations, etc. These are certainly valuable to the student of Christian Science and to the general reader. But the Concord team stayed focused by constantly asking, “What is the work that The Mother Church is uniquely capable of doing and that we are uniquely commissioned to publish? Let other institutions publish other useful tools.”

Among the specialized programming challenges, it was proving particularly difficult for users to unambiguously specify citations—the passages they were researching in the books. One of the central uses of the Concord program is to search and capture these passages, be it for individual study, writing articles, or creating readings for use in church services. At one point during final testing, a citation bug popped up that just couldn’t be fixed. Many attempts only created bigger problems. The product obviously couldn’t be released until this was solved. The developer working on the marking issue later told me that at about one o’clock in the morning he was prayerfully led to take a radical step, very rare when a product is so close to shipping—he rewrote the entire code for marking citations. The code was finished that morning, and the bug was vanquished. Remarkably, another programmer had an almost identical experience with the notebook on the eve of its shipping. He, too, worked all night, completely refactoring (reorganizing) the relevant code, and had it perfect by morning.

The introduction

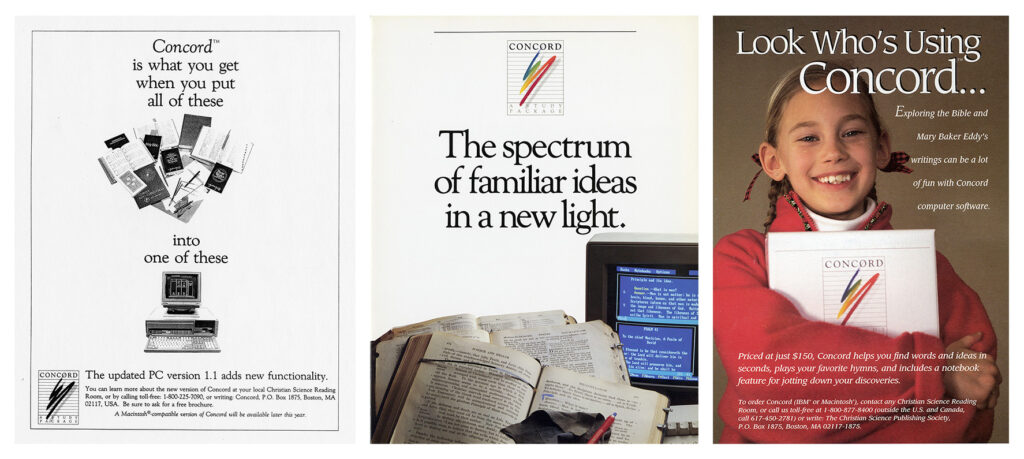

DOS Concord was released on August 31, 1988. It hit the market for $550, a price comparable to word processing and accounting software of the time. The revenue was mostly profit, enabling it to soon pay for its development cost.

The question arose as to how this completely new product would be introduced to Christian Scientists worldwide. The alpha and beta testers constituted a small but important beachhead of informed communicants, but much more research was needed.

One of the paths forward opened up at Principia College, which at that time conducted two programs each summer, attended by hundreds of people participating in courses and other activities. The college had a basement computer lab with 12 PCs available for giving instruction. In 1988 I was able to teach about six dozen attendees the basics of DOS Concord over the course of the summer. In three one-hour sessions, each learner performed various searches, built notebooks of their research into the Bible and Eddy’s writings, and printed selections of that material. Other instructors joined me in continuing to teach Concord at Principia each summer for many years. And those enthusiastic learners taught others. Simultaneously, marketing materials were made available to Christian Science churches and Reading Rooms around the world. There were also ads in the Publishing Society’s periodicals.

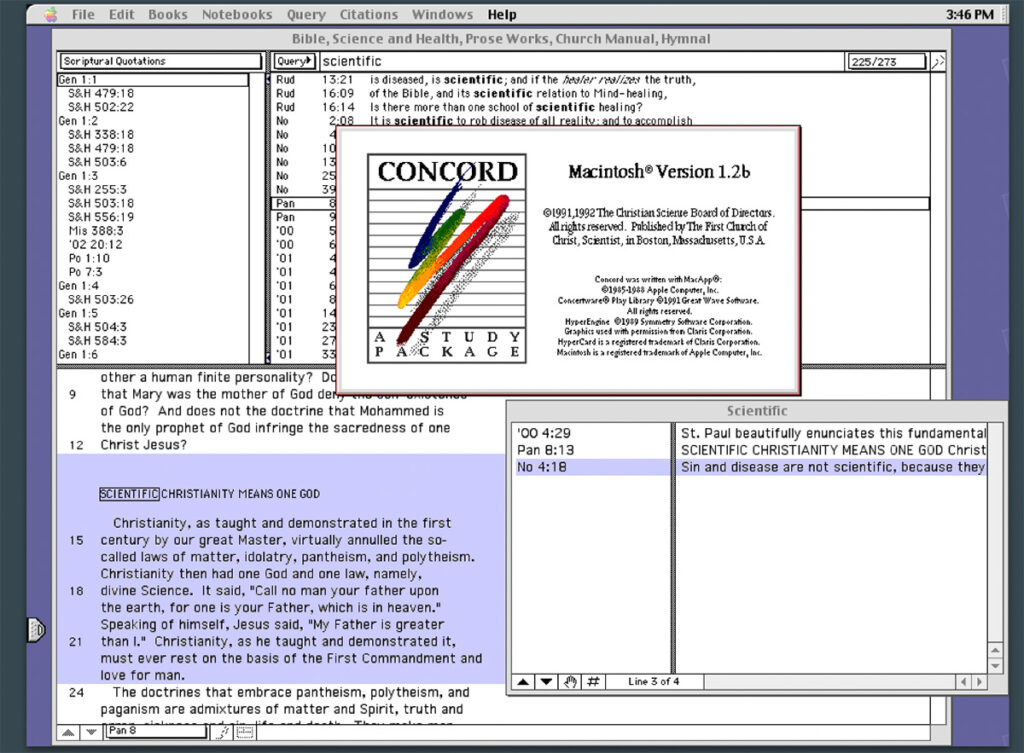

Concord, A Study Package for Macintosh, 1991. © The Christian Science Board of Directors.

Two years later, a parallel product was introduced—the Apple Macintosh version of Concord. Using MacApp Pascal, an early object-oriented language, it gracefully incorporated the Mac’s graphical and musical strengths. This Mac version enabled the user to view and print from the books in a wide variety of fonts and sizes—something especially helpful to those desiring large print. With its excellent audio features, complete with four-part harmony, the Mac was wonderful for hymns. Today it remains the only Concord version that plays hymns with a variety of instruments, including piano, organ, and guitar. Macintosh Concord 2.0 was released in 1991. Some minor revisions to both the DOS and Mac versions were released over the next decade.

Concord matures: the path forward

The advent of Microsoft Windows 95 demanded a major Concord update—its third version. Released in 1999, it brought to PC users the fully featured graphical user interface (multiple windows, icons, mouse moves, etc.) and a wide variety of fonts (similar to the Mac version). It was written in C++ and incorporated the Verity search engine. Now PC users could also read and print out texts in virtually any size font.

These were the years when the internet was exploding onto the scene. The first widely available browser (Mosaic) appeared in 1993. Amazon was launched in 1994, and eBay in 1995. Internet users expected more sophisticated user experiences and searches. Some of this sophistication was available in the 1999 Concord edition. For example, a search for the word *mortal* also retrieved citations using such words as mortals, immortal, and immortality. Conceptual searches (using a built-in thesaurus) enabled a search for the word frustrate (which does not appear in Science and Health) to impressively return this relevant citation on page 283 of the book: “Mind is the source of all movement, and there is no inertia to retard or check its perpetual and harmonious action.”14 However, this third version only ran on PCs.

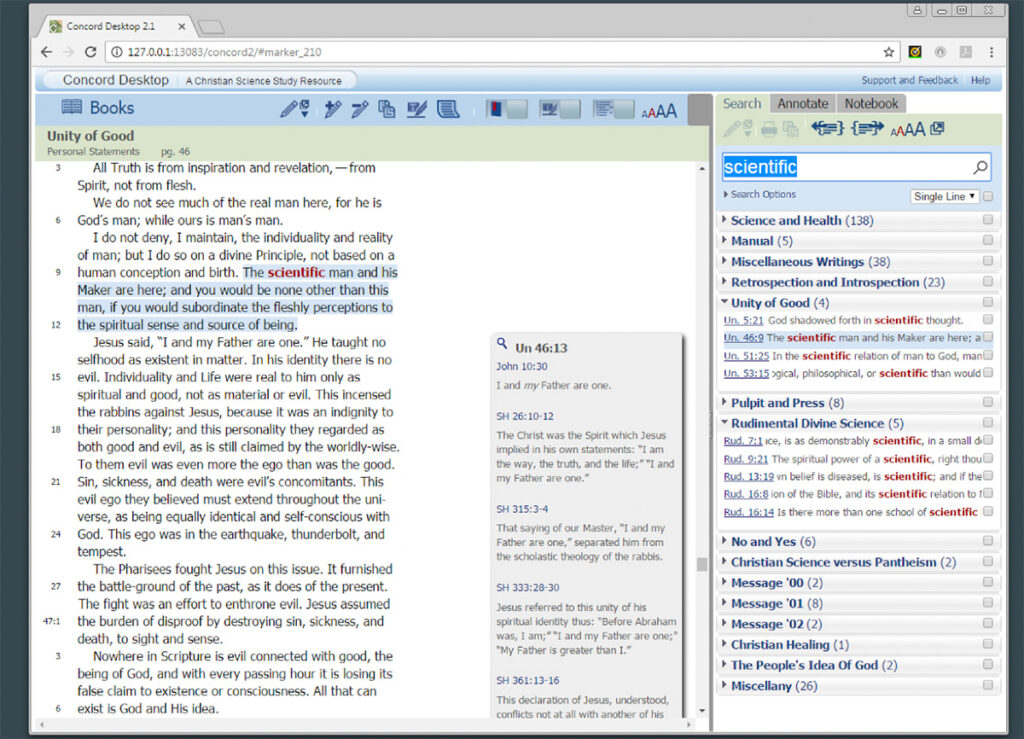

By 2009 Mac owners were feeling abandoned. The Mac Concord (last updated in 1991) would only run on decade-old machines. Moreover, the internet itself could no longer be ignored. Software had been moving to the internet for a generation, but not everyone had access. The church therefore developed Concord Desktop, a hybrid model. The team separated the application into three major components:

- The server—a Java application that could store, retrieve, parse, and search the books, store notebooks, and host multiple Concord accounts for a public Concord Online service.

- The user interface—a mostly JavaScript and HTML application that ran in the user’s browser, displaying the text from the books.

- The desktop—a customized version of Firefox Mozilla that could launch both the server and the user interface on any desktop computer.

During the development, new versions were constantly tested, to ensure that all citations retrieved from the Bible Lessons in the Christian Science Quarterly over the past 60 years were accurate. This fourth version of Concord had significant advantages. It gave users an experience of being online, even if they were not connected to the internet. It also ran on both Microsoft Windows PCs and current Apple Macintosh computers.

However, this also meant that every Concord user was now running a web server and a Firefox browser, and that this combination had to run in widely varying hardware and software environments. Much could go wrong with this complex brew. Furthermore, every Concord revision required the user to load it—but not all users did so, which made it very difficult for the support team to troubleshoot problems. Indeed, Concord Desktop required a huge support effort by the church’s technical team. After several updates (through 2012), it became clear that this model was not financially sustainable; this was the time to move the web server off each user’s computer and place it on a central system, where Concord could be maintained, improved, and updated at a single location. This would make all improvements immediately available to every user, worldwide.

The interface for Concord Desktop and Concord Online, released in 2009 and 2011, respectively. © The Christian Science Board of Directors.

The fourth Concord team had already begun to move the server off the desktop in 2011. They released Concord Online, with a monthly subscription plan that could be accessed wherever an internet connection was available. This even permitted a limited mobile-phone experience for users.

In 2013, The Mother Church launched JSH-Online, making its religious publications fully accessible to subscribers, which included Concord Express—a basic version that allowed limited, search-only capability. Concord Express was replaced by Concord Guest Access in November 2018, with the release of the fifth version of Concord.15

The current Concord

A new team was formed in 2015, tasked with building the fifth major version of the product. It was challenged to overcome the support and financial burden posed by the previous Concord versions. As Jason Hunsberger, the team’s leader, recounts:

In the years since the fourth version of Concord was released, a computer revolution had taken place in society: the smartphone. This transformation started in 2006, with the release of the iPhone, but had become fully realized by the mid-2010s. By 2015, we now lived in a society with ubiquitous mobile internet access in our pockets. An entire generation had grown up with the expectation that anything worth doing was going to be available on their smartphone or tablet….

…Concord needed to be updated to provide a first-class, touch-based interaction model in a smartphone and tablet form factor. This would require a complete reconsideration of the Concord user experience.

Additionally, Hunsberger remembers, the Publishing Society was at that time in the last stages of a new version of the Christian Science Hymnal. It was an extension of the 1932 edition. Released in 2017, this would replace the spiral-bound Christian Science Hymnal Supplement: Hymnal 430–462, which was issued in 2008. There was a desire for these two books to be considered one hymnal—and to be available on Concord in a way that would make them feel seamlessly integrated.

Moreover, there was an additional demand for a new version of Concord from a group that was largely invisible: the committee that prepares weekly Christian Science Bible Lessons. In doing its work, the Bible Lesson Committee had been using a combination of DOS Concord and Macintosh Concord for a quarter century. The process was tedious and distracting, and depended on keeping ancient computers in working order. Any new Concord edition would have to address this.

Questions and challenges

Other issues were raised: Was the church best served by a new fully-featured version of Concord? Or could a simpler solution meet users’ needs (such as publishing the books in web format and letting browsers do searches)? After extensively studying the 1903 edition of the print concordances to the Bible and Eddy’s writings, and subsequent editions, as well as the available documentation, the team reached some conclusions. Hunsberger remembers that Eddy endorsed the printed concordance to her works, as facilitating the study of Science and Health, and that “for over 80 years it was the exclusive, authorized means to perform systematic study of her writings.” In that sense, he says, “Concord is a humble manifestation of decades of progress in human thought,” allowing for “a new, more convenient, faster, and flexible study tool,” that offered “almost instantaneous reference lookup for inspiration, healing, digital sharing, or printing; a fully digital, in-context Bible Lesson experience: tools for citation gathering, curation, and editing for deep-dive analysis; simple church service reading development; and expansive textual annotation.”

Next in the challenges that the team for the fifth version of Concord sought to address was the maintenance, support, and financial burden of the previous version. Concord needed to be supported by a sustainable business model. By 2015, web-based Software as a Service (SaaS) had become a broadly accepted, successful model. Customers to the service pay a monthly or annual subscription fee to support (at enough scale) ongoing maintenance and development. This revenue would allow the church to maintain a small team of developers to ensure that Concord could quickly respond to changes in technologies, new operating system innovations, and web browser updates.

As the team began digging into the work, they discovered that the texts themselves had evolved a long way from the 10.5-inch computer tapes of 1986. Over the decades, through the evolution of multiple Concord versions, the texts had become populated with indexing markers, editorial comments, and so forth. Because it was inconsistent, this “metadata” was in some cases actually creating “blind spots”—zones of book text that could not be found by a search. Hunsberger remembers:

This team performed a full, top-to-bottom proofread of the Concord digital texts, aligning it to the fully proofed, authorized, standard editions of Mrs. Eddy’s works. This included a full review and alignment of all Bible cross-references to the concordance Bible cross-reference indexes.

One of the key innovations of this version of Concord was revamping the interface to be suitable for mobile use. [Many] users think of Concord as a memory aid to find a citation they did not fully remember. In this digital medium, we were conscious of the long-term challenge this posed [to] the student of Christian Science—Concord was intermediating the student’s experience with the books. The books were becoming abstracted and atomized into out-of-context partial quotations. To counteract this trend, the team felt it was essential that Concord be a place where the user might just be coming in for a quick quote, but could feel so welcomed that they would stay for a while. The team poured significant effort into improving the readability of the text, using the latest digital typesetting and font rendering technologies to encourage long-term reading. The team felt a need to be faithful to the books and respect how they are printed, to the extent that technology allowed. In this regard, the team often [pushed] at the limits of text rendering in web browsers, trying to get the text to render as faithfully as possible.

According to Hunsberger, the team was successful at addressing each of the challenges set before it. The Bible Lesson Committee was able to begin using this new edition of Concord in 2018. A popular public beta site launched early 2018 that year, celebrating Concord’s 30-year anniversary with the general availability of its subscription offering on October 31.

As of 2023, Concord had several thousand subscribers supporting its ongoing development. Students of Christian Science were sending in stories of how much their practice of Christian Science was benefited by having the same Concord experience on their phone as at their desktop. They said the search and study tools had led them to new discoveries and shared how much they enjoyed reading the texts.

Not long after this release, the wisdom of moving away from Concord Desktop, with its built-in web server, was dramatically vindicated. In 2020 Mozilla’s Firefox web browser had evolved to the point that Concord Desktop would no longer run it on my PC. The extensive and thorough effort of the project team now proved quite timely. Moreover, by 2023 the Concord team had incorporated more than 50 updates, revisions, and enhancements. Because it only runs on the central server, every one of its thousands of subscribers now uses this fully updated version.

Ripples in the publishing pond

There’s more to the Concord story. Not long after DOS Concord’s 1988 release, people had begun printing and distributing the Christian Science Bible Lessons, using the program to print the full text of each citation. Up to that point, people usually read these Lessons directly from the Bible and Science and Health. These printouts were derivatives of the Christian Science Quarterly, a copyrighted publication of the Publishing Society. Thus, distributing them constituted violation of copyright. The church again needed to assert copyright in order to preserve it.

Thus it was determined that the Publishing Society needed to print a full-text edition of the Quarterly. But this raised concerns of reduced sales of the Bible and Science and Health. It was suggested (hoped) that Bible Lesson printouts might be used lightly (when traveling, commuting, etc.), and that people would continue to use the books from which the citations originated. While it was natural to expect that Concord would result in the sale of fewer print concordances, it was not clear the degree to which the software program, together with the full-text edition of the Quarterly, would affect sales of the Bible and Eddy’s writings in book form.

The question raised years earlier remains: has this software drawn people closer to the Christian Science pastor, or has it nudged them away from it? Concord itself enables its users to read the weekly Bible Lesson in the context of those two books. Each citation is presented in situ—a particular page, in a particular chapter, in a particular part of a book.16

Sample of print advertisements for the Concord program from its first decade. © The Mary Baker Eddy Library.

The future

Eddy foresaw continuing, vital relevance for the Bible and the Christian Science textbook. “Centuries will intervene,” she wrote, “before the statement of the inexhaustible topics of Science and Health is sufficiently understood to be fully demonstrated.”17

Concord’s story now spans over a third of a century. And I know a few students of Christian Science who have retained primitive PCs (running DOS) and medieval Macs (running MacOS 9), just so they can continue using its two inaugural versions. Concord versions notwithstanding, people continue to remark how each new version opens new vistas in their study of Christian Science.

With technologies such as virtual and augmented reality, these books could one day appear suspended before our eyes with three-dimensional vividness. In another generation, a mere thought might bring them instantly to view. The Bible and Science and Health will continue to appear in new, fresh forms. But the Christian Science pastor will always remain to support the purpose of The Mother Church, “healing and saving the world from sin and death.”18

Tom Fuller holds a doctorate (focused on artificial intelligence) from Washington University in St. Louis. He taught math and computer science for three decades at Principia College, serving for a year as its acting president. He worked at The Mother Church from 1986 to 1989.

For more discussion on this topic, listen to our Seekers and Scholars podcast episode “Concord—spiritual quest and ‘the word’ in the computer age.”

- See for example https://kingjamesbibledictionary.com/BibleFacts

- Alexander Cruden, A complete concordance to the Holy Scriptures, or, A dictionary and alphabetical index to the Bible, 1768. https://archive.org/details/completeconcord00cruduoft/page/n9/mode/2up

- The First Church of Christ, Scientist, in Boston, Concord A Study Package: User Manual, 1991, xvi.

- Isabel Ferguson and Heather Vogel Frederick, A World More Bright: The Life of Mary Baker Eddy (Boston: The Christian Science Publishing Society, 2013), 85; Yvonne Caché von Fettweis and Robert Townsend Warneck, Mary Baker Eddy: Christian Healer Amplified Edition (Boston: The Christian Science Publishing Society, 2009), 104.

- Fettweis and Warneck, Christian Healer, 206, 532–534.

- Reminiscences – Laura C. Conant, pp. 15–16.

- In her writings. Eddy identified seven primary synonyms for God: Principle, Mind, Soul, Spirit, Life, Truth, and Love.

- Eddy passed away on December 3, 1910. Shortly after this, the last edition of Science and Health was printed in 1911.

- Act of Congress: House Rule 1866, Private Law 92-60-December 15, 1971.

- Christian Science Text’s Copyright Is Ruled Illegal by Appeals Court,” The New York Times, 23 September 1987, A24.

- Mary Baker Eddy, “Mind-healing History,” The Christian Science Journal, June 1887, 117.

- See the Library’s article Women of History: Countess Dorothy von Moltke.

- I was not at this meeting, nor the one mentioned in the previous paragraph, but the manager was, and gave me these quotations.

- Eddy, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 283.

- https://concord.christianscience.com/previous-versions/

- See Jennifer McLaughlin and Jason Hunsberger interviewed by Susan Kerr, “Concord and its role in study,” Journal, July 2018, 9.

- Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 84.

- Eddy, Manual of The Mother Church (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 19.