Women of History: Countess Dorothy von Moltke

This photograph of the Committee for the German translation of Science and Health was probably taken at the Hotel Beaconsfield, Brookline, Massachusetts. From left to right (horizontally): Helmut von Moltke, Ulla Shultz (later Oldenbourg), Adam H. Dickey, Renata Hermes (later King), Dorothy von Moltke, Theodore Stanger, c.1910. P07507. Unknown photographer.

Countess Dorothy von Moltke (1884–1935) helped spread word of Christian Science to German-speaking people around the world. She also served on the committee that first translated Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures into German. A South African native, she moved to Germany as a new bride, when the country was on the precipice of decades-long turmoil. Through many trials and challenges, she charged forward, holding her family and their estate together with a grace born of experience, personal character, family support, and reliance on Christian Science.

The only child of Sir James Rose Innes and Jessie Dods Pringle Innes, she was born in South Africa in 1884. Both her parents came from families that had settled early in the country. Her father, who served in South Africa as attorney general and later as chief justice, was an early advocate for Black rights in the country. Her mother was an early champion of women’s rights.1

Although the three formed a tight family unit, that connection was tested when Dorothy’s mother took her to Europe in 1902. While in Germany she met Count Helmuth von Moltke,2 and they married in 1905.3 They had five children: Helmuth James (1907–1945)4; Joachim (Jowo) Wolfgang (1909–2002); Wilhelm (Willo) Viggo (1911–1987); Carl Bernd (1913–1941); and Asta Maria (1915–1993). The couple taught Christian Science to the children, but did not force them to practice it, letting them choose their own path.5

Through marriage, Dorothy became not only a countess but also lady of “Kreisau,” the house on the von Moltke estate in German Silesia (now Poland). Filling this role was a large task, but she succeeded, even during the financial and political turmoil of World War I and Hitler’s rise to power.6 She entertained guests such as the socialist writer Olive Schreiner (1855–1920) and dined with Prussian royalty.7 Over the years, Germany’s instability hit the von Moltke estate hard, and Dorothy employed her own budget-balancing skills, as well as financial help from her parents, to keep the estate from ruin, as indicated in this letter to her father:

Thank you so much for the Draft, dear Daddy; I have managed rather better this half year and have in consequence saved about £10. Then from 1st June Helmuth has of his own accord given me £10 a month for my daily expenses when I am not with him etc. As however I can get on quite well without it, I mean to put it all in the savings bank, so as to have a fund for emergencies.8

Yet her astute management was not confined to Kreisau; she also used some of her personal funds to expand the village kindergarten.9 She also taught English to German Christian Scientists who wanted to read Mary Baker Eddy’s book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures.10

Dorothy fully embraced her new religion, as well as her new country. Although her parents had raised her in the Anglican Church, she was introduced to Christian Science through her husband and became a faithful follower.11 12 This devotion was evident in letters to her parents. In 1909 she wrote this to her father:

Let me say dear Daddy how very greatly I appreciate your interest in a subject in which your little girl is so intensely interested, and I think it sweet of you to trouble about it at all, even if it is for her sake…. In C.S. [Christian Science] the healing of sickness is really a secondary consideration, and its chief value (apart from the help and comfort one is thereby able to give) is that it is a proof that we are gaining a small understanding of the truth…… in Christian Science I have found a rational answer to all my questionings and … I have found the most wonderful peace, the panacea for all fear, and the greatest incentive not only to pure and right living, but to pure and right thinking too…. let me only add that it is not a new sect or religion, but simply the teachings of Jesus Christ.13

The von Moltkes remained dedicated to Christian Science. In 1907, they traveled to the city of Hannover for Primary class instruction, taught by Bertha Günther-Peterson, CSB.14 Helmuth had known that Christian Science teacher from years earlier, when in 1899 she had healed him of a nerve disorder, prompting his interest in the religion. In 1923 both Helmuth and Dorothy joined The Mother Church. They also wrote articles for the Christian Science periodicals. In March 1910, Helmuth published “Disharmonie ist unwirklich” in the German magazine Der Herold der Christian Science. A reprint in English, “Discord Unreal,” appeared on September 14, 1912, in the Christian Science Sentinel. Dorothy wrote “The Works of God Made Manifest” for the Sentinel, as well as “Our Garden,” which appeared the following year and included this:

The serpent mentioned in the allegory which begins in the second chapter of Genesis, is defined by Mrs. Eddy as “a lie; the opposite of Truth, named error; … the belief in more than one God; … the first lie of limitation; … The first audible claim that God was not omnipotent and that there was another power, named evil, which was as real and eternal as God, good” (Science and Health, p. 594). How often do we listen to this lie, acknowledge its power, yield to its insinuations, eat of the fruit it offers us, and then suffer the direful consequences of our folly, in just the same way that Adam and Eve did!15

Along with many other German speakers, the von Moltkes felt they needed Mary Baker Eddy’s book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures in the German tongue. In 1897 Günther-Peterson offered to translate the key text into German. At that time Eddy was hesitant—she wanted a translation that would embody the essence of her original words.16 Yet she had also expressed interest in translation.17 Since it was first published in 1903, Der Herold der Christian Science had been paving the way for properly translating Christian Science terms into the language.

As well, Helmuth von Moltke’s distant cousin Countess Fanny von Moltke wrote to Eddy about a translation in 1907. Only later did he realize that they both had been inquiring at the same time. In a May 24, 1907, letter (original in German), he included this plea:

Just when I had finished writing my letter I found the letter by Countess Fanny von Moltke in Der Herold der Christian Science Vol. 4, No. 2 that had been written in response to your refusal in regard to a translation of Science and Health. Yet, since I am convinced that the time has come that a translation into German is necessary, I shall send my letter. My conception of the love of God is too great to think He would give His revelation to one nation and not wish that any other nation should take part in it….18

Despite the urgent calls from her German followers—as well as her own desires to see a German edition—Eddy remained reluctant to translate the English text. Chief among her concerns was that the meaning of her carefully chosen words would be lost in translation, obscuring Science and Health’s precise and complete articulation of Christian Science. In 1904 she had written this in a letter to Fanny von Moltke:

A retranslation of my book would be filled with errors. In a true translation for you of Science And Health I would joy to be a German to the Germans in language as I now am in spirit. When first I wrote “Science And Health” I deeply desired to have that book translated properly and sent to Germany. The idealism of the Germans seemed to me quite in accord with the realism of Christian Science in other words it seemed to be more spiritual than that of most languages. But I have learned at length that neither the German nor French language is capable of expressing the absolute Science of Christian Science.19

But by 1907 the tides had begun to turn in Eddy’s thought, and she was more receptive. On his own accord, Helmuth attempted (probably without great success) a translation of the chapter “Recapitulation” in Science and Health. While Eddy was wary of such a project, she did not oppose it.20 At length she gave the green light to a German translation in 1910.21

While Eddy passed away not long after giving that approval, translation work began the following year. Dorothy and her husband, along with three other translators, joined the committee appointed to begin the work and set sail for Boston. The task was arduous and took seven months of dedicated labor.22 Dorothy was an integral member of the committee, because she was the only native English speaker who also spoke German. As such, she was responsible for translating the completed German text back into English, so that Adam H. Dickey could ensure correct translation from a metaphysical standpoint.23 24

While in Boston the von Moltkes’s sole focus was on the translation work. But they did find time to see something of what the city and the New England region had to offer the traveling elite. This included the Harvard Library and the Boston Public Library, where they explored various books in order to properly translate philosophical, technical, and physiological terms into German.25 Finally, in 1912, the group saw the fruits of its labors, in the publication of the German edition of Science and Health.26

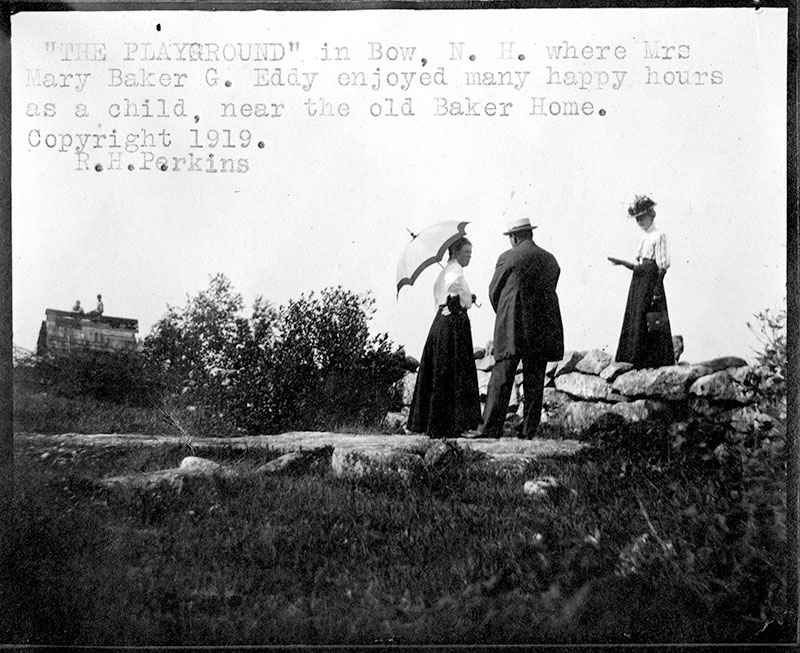

In this photograph, Dorothy von Moltke (far left) is seen exploring the grounds of the “old Baker home” in Bow, New Hampshire. Circa 1919. P06153. R.H. Perkins.

After completing their work in Boston, the von Moltkes set sail, gathered Helmuth James, Jowo, and Willo in Germany, and went on to South Africa. There Dorothy gave birth to Carl Bernd in 1913, and to Asta Maria in 1915.27

On June 11, 1935, Countess Dorothy von Moltke passed away unexpectedly. Her family was understandably grieved, with Helmuth remarking, “Kreisau ohne Mami ist zu triste! [Kreisau without Mami is so sad!]” and her father noting in his autobiography that with her death “the bottom dropped out of our little world.”28 But she had left a lasting gift to the world through her translation work, which opened the door to the publication of Science and Health in many other languages that followed the German edition.29

This blog is available on our French, German, Portuguese, and Spanish websites.

Listen to Women of History from the Mary Baker Eddy Library Archives, a Seekers and Scholars podcast episode featuring Library staffers Steve Graham and Dorothy Rivera.

- Catherine R. Hammond, Island of Peace in an Ocean of Unrest: The Letters of Dorothy von Moltke (N.P.: Nebadoon Press, 2013), 5.

- Dorothy von Moltke’s husband, Helmuth von Moltke (1876–1939), had paternal ancestors with the same name—which could be a source of confusion. Dorothy’s husband was the grandnephew of Helmuth Karl Bernhard von Moltke (1800–1891), also known as “Helmuth von Moltke the Elder.” A field marshal, he helped lead Germany to victory in the Franco-Prussian War. The next in line was his nephew, Helmuth Johannes Ludwig von Moltke (1848–1916), nicknamed “Helmuth Johannes Ludwig von Moltke the Younger.” He also served in the German military as Chief of the German General Staff. While these men are usually referred to as “Elder” and “Younger,” Dorothy’s husband was only referred to as “Helmuth” or “Count Helmuth.” Following the tradition, Dorothy and Helmuth named their firstborn son Helmuth James von Moltke (1907–1945). The Nazis executed him in 1945, for his participation in the Kreisau Circle, a German resistance group, after he tried to warn another resistance group, the Solf Circle, about infiltration. Despite having never officially adopted the Christian Science faith, Helmuth James had absorbed his childhood lessons in prayer and spirituality. This came to the surface during his time in prison and solidified his identity as a Christian. See Catherine R. Hammond, Island of Peace in an Ocean of Unrest: The Letters of Dorothy von Moltke (N.P.: Nebadoon Press, 2013), 282, 318–319 and Anton Gill, An Honorable Defeat (New York: H. Holt, 1994),160–162.

- “Dorothy Rose Innes,” The Olive Schreiner Letters Online https://www.oliveschreiner.org/vre?view=personae&entry=49

- On January 23, 1945, Helmuth James von Moltke was executed by the Nazis for his involvement in the German Resistance.

- Hammond, Island of Peace, 283.

- Michael Balfour and Julian Frisby, Helmuth von Moltke: A Leader Against Hitler Balfour (London: Macmillan, 1972),15.

- Olive Schreiner to William Philip (‘Will’) Schreiner, 24 July 1914, UCT Manuscripts & Archives, Olive Schreiner Letters Project transcription.

- Catherine R. Hammond and Dorothy von Moltke, Island of Peace in an Ocean of Unrest, 39.

- Michael Balfour and Julian Frisby, Helmuth von Moltke: A Leader Against Hitler (London: Macmillan, 1972), 16.

- Hammond, Island of Peace, 50.

- Hammond, Island of Peace, 242.

- While Dorothy and Helmuth von Moltke no doubt saw themselves as Christian Scientists, it seems likely that before the First World War it would have been extremely difficult—perhaps impossible—for them to withdraw from the Lutheran church and remain members of the German nobility. At that time this was the state church, and the count’s responsibilities may even have included serving as “sponsor” for the Lutheran church in Silesia. The couple raised their children as Lutherans. The von Moltkes did not join The Mother Church until following the war, after the monarchy (and state churches) had come to an end in Germany and the Weimar Republic was established. Long before the rise of Nazism in Germany, Christian Scientists faced restriction.

- Hammond, Island of Peace, 243.

- Hammond, Island of Peace, 28.

- Countess Dorothy von Moltke, “Our Garden,” Christian Science Sentinel, 5 April 1913, 604.

- Calvin Frye to Bertha Günther-Peterson, 24 May 1897, V01525.

- Mary Baker Eddy to Julia Field-King, 8 June 1896, F00125.

- Helmuth von Moltke to Eddy, 24 May 1907, IC084.18.002.

- Eddy to Fanny von Moltke, 1904, L09568.

- Mary Baker Eddy to Helmuth von Moltke, 11 June 1907, L14083.

- Eddy to Allison V. Stewart, 31 March 1910, L03271; Stewart was Eddy’s publisher.

- See Hammond, Island of Peace, 271–278.

- Hammond, Island of Peace, 271.

- Eddy had asked Dickey, who served as her secretary from 1908–1910 and was now a member of the Christian Science Board of Directors, to supervise the project and ensure the metaphysical correctness of the translation.

- Hammond, Island of Peace, 276–277.

- “Science and Health Translated,” Sentinel, 30 March 1912, 611.

- Hammond, Island of Peace, 279–280.

- Hammond, Island of Peace, 216.

- Currently Science and Health is available in a total of 17 languages, including Braille.