Women of History: Florence E. Boynton

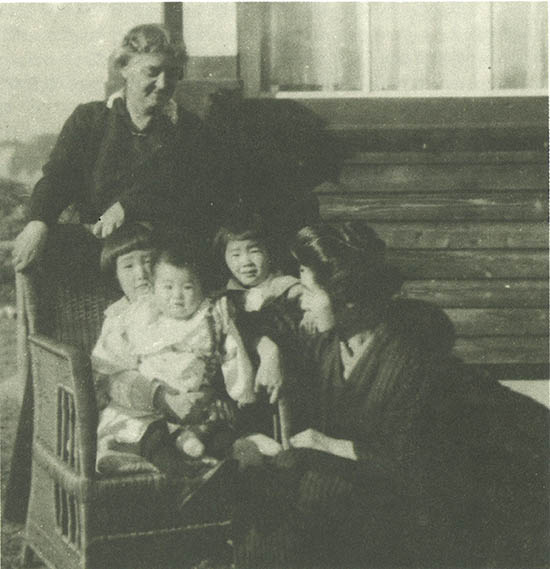

Florence Boynton with Miyo Matsukata and her children, circa mid–1920s.

Photo courtesy of Nishimachi International School.

Listen to this article

Florence Eleanor Boynton (1876–1942) was an accomplished educator and self-described “born teacher” from the San Francisco Bay Area. Students described her neat appearance, beautiful head of “marcel waved” hair, hazel eyes, good sense of humor, and musical voice.1 A strict and unwavering disciplinarian, she was also motherly and warm. She expected her pupils always to excel. “What is worth doing must be done well,” she would tell them.2

Boynton had a spirit of adventure. She lived in France between 1901 and 1902 and agreed to travel to Tokyo around 1911, as a private tutor for the four children of an American businessman.3 When the assignment ended, she went back to the United States for a few years, before returning to Japan in 1915 to teach at a middle school.

This time Boynton ended up spending nearly three decades in what became her adopted country. During that time she was connected to some of Japan’s first Christian Scientists. The part she played in educating their children—as well as the adults—left a lasting legacy on the history of Christian Science there.

Related Story: Anna Mallory and Christian Science in Yokohama

“Until reaching Honolulu we did not know that Christian Science had found a permanent foothold in Japan, and so we had a happy surprise when we arrived at Yokohama, and found the Lesson-Sermon was being read each week by a small gathering.” So wrote serviceman K.D. Grant in an October 1908 letter to Mary Baker Eddy, speaking of the group in Yokohama, Japan, that eventually was recognized as a Christian Science Society.1 The Christian Science Sentinel later gave a little history: “Yokohama Christian Scientists began to meet in the home of one of their group Easter Sunday, 1907. As the number of attendants increased, it became possible, in 1919, to organize Christian Science Society, Yokohama.”2

Anna Mallory (1857–1948) of Yokohama was an American woman and one of the earliest Christian Science practitioners in Japan.3 While her work there was likely confined mostly to Europeans and Americans interested in Christian Science, she clearly came to love her adopted country. She lived in Japan from about 1910 until 1943, when forced to leave in the middle of World War II.

Mallory’s testimony of divine protection during the massive Great Kanto earthquake of 1923 speaks of her trust in God and love for Japan. It was published in the January 19, 1924 issue of Christian Science Sentinel. You can read it here.

On her return to the United States, at the age of 86, Mallory was aboard the Swedish vessel Gripsholm. Chartered as a “repatriation ship,” it enabled exchanges of both military prisoners and civilians. Along with hundreds of Protestant and Catholic missionaries, she sailed through the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic, by way of the Cape of Good Hope. This much longer route was considered safer than crossing the Pacific.4

Shortly after their arrival in the US, The Christian Science Monitor interviewed Mallory and Lula Dewette, a Yokahama resident and founding member of the Christian Science Society there. The article describes their solidly loving response to the challenges facing them, even as it became more and more apparent that they would have to leave their longtime home. You can read the full article here. It includes interesting accounts of how the two women approached difficult wartime experiences. The interviewer concluded, “Both women have only kindly recollections of their long sojourn in Japan.”5

After returning to America, Anna Mallory lived the rest of her life at Pleasant View Home in Concord, New Hampshire, which at that time was a facility for retired workers in the Christian Science movement.

1. “Letters to Our Leader,” Christian Science Sentinel, 9 January 1909, 371-372.

2. “Japan,” in “Extracts from Reports of Christian Science Committees on Publication,” Christian Science Sentinel, 23 May 1936, 749. The Story of Christian Science Wartime Activities 1939-1946 (Boston: The Christian Science Publishing Society, 1947) notes that the society was forced to dissolve by governmental authorities in 1940 (298). It never reopened.

3. The first practitioner was Zenjiro Ikuta (1881–1944) of Tokyo, listed in The Christian Science Journal until 1938. Little is known of him; census records indicate he was a longtime US resident before returning to Japan in the 1920s.

4. For more information on the voyage, see “1,440 on Gripsholm Wildly Happy Here: Reticent on Trials,” The New York Times, 2 December 1943, 1, 18.

5. Barbara E. Scott Fisher, “Two Repatriated Americans Can Look Back With Pleasure at Long Sojourn in Japan,” The Christian Science Monitor, 7 December 1943, 13.

Christian Science takes root

A published account in the Christian Science Sentinel describes a healing that introduced Boynton to Christian Science in the Bay Area. It occurred sometime between 1911 and 1915, after she’d returned from her first teaching assignment in Japan. She wrote that she was “in wretched health, broken physically and mentally, and in great fear of becoming a rheumatic invalid.” Having found no help through medicine or her own religion, she read a Sentinel. This launched her inquiry into Christian Science healing. “As I gained the understanding of this new-old religion,” she recounted, “my healing came, enabling me to take my place as a useful member of society.”4

She brought this newfound love of Christian Science on her next trip across the ocean in 1915. By the early 1920s she was giving private English lessons to Shokuma Matsukata, the son of a prominent Japanese politician. His wife, Miyo Matsukata (1891–1984), was also a student of Christian Science. The two women formed a close friendship, sparked by their mutual love of the religion. Eventually they were instrumental in founding Tokyo’s first Christian Science Society in 1931.5 Boynton joined The First Church of Christ, Scientist (The Mother Church) in 1924, while still living and working in Tokyo.

Matsukata had always appreciated the American education that she received growing up in the United States, and she wanted the same for her own children. She decided to hire Boynton as their private English tutor and invited other families, who were also studying Christian Science, to join the classes.6 It’s worth noting that no Japanese translations of Christian Science literature, including Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, yet existed; it was essential to know English in order to study the religion.

An instructor with unique qualifications

In contrast with Japanese education, Boynton taught her young students English in a manner that included a freedom and expressiveness characteristic of American culture. Emi Abiko was one of those children. Her book A Precious Legacy: Christian Science Comes to Japan devotes an entire chapter to Boynton, describing how her lessons had the dual purpose of teaching a language and sharing the truths of Christian Science. In this way, the children were learning the history and foundation of a faith that had American roots. At recess, for example, they put together jigsaw puzzle pieces that Boynton had made of scenes from The Mother Church in Boston, as well as of Mary Baker Eddy’s homes in Massachusetts and her birthplace in New Hampshire. Christmas was celebrated at the Matsukata home, and even the dinner table included name cards with quotations from the Bible and Science and Health.7

According to Abiko, Boynton believed that “education means to bring out the good which God has already given each child.”8 When Miye Matsukata (1922–1981) brought home a beautifully designed cardboard model of a house, Boynton helped to arrange formal painting lessons for her young student with Gyokushi Atomi, one of the finest artists in Japan. Miye eventually became a recognized artist herself, working as a jewelry designer and metalsmith in the United States.9

Boynton paid meticulous attention to detail and expected the same of her students, from their neatly pressed clothes to their studies.10 Sometimes her strict adherence to rules and discipline came with consequences—such as when she insisted that young Haru Matsukata retrieve a diction notebook she’d left at a friend’s home. While she was on her way there, a strong earthquake struck. With collapsed cottages blocking Haru’s path, her father had to rescue her. “Miss Boynton was a real stickler for diction…,” she remarked. “I always brought my notebook to class after that!”11

Through the eyes of her students

When the 1923 earthquake struck Japan on September 1, Boynton’s house in Tokyo was seriously damaged. The Matsukata family invited her to temporarily stay with them. She ended up living there for the next two decades, taking complete charge of the children’s education.12 It was likely not always easy for Miyo Matsukata to share her role as mother and influencer, especially given Boynton’s strong character. Nevertheless, Miye remembered her mother quietly bearing any struggle she might have had, for the sake of her children’s education: “It was clearly my mother’s generosity of spirit that made it possible for two women to live together in one household and to let the children be taught, guided, and molded without jealousy or covetousness of the children’s affections.”13

Matsukata valued her children’s education far above preparing them for an early marriage. Confronting the longstanding traditions of her Japanese relatives, she made it clear to them that her daughters would attend college in the United States. Eventually all six (including one son) attended Principia College, a school for Christian Scientists in the American Midwest.14

In fact, 13 of Boynton’s students went to Principia.15 Although she had prepared them well for this step in their education, many still felt caught between two cultures. “At times I felt almost bitter that I had been raised to be so different from other Japanese,” recalled Haru Matsukata. “Why couldn’t I have been brought up the ordinary way, I would think, since being different didn’t seem to make me a real American either?”16 Not until she had graduated from college and returned home to Japan did she take up a thorough study of her own country’s history, involving details she couldn’t explain to her American friends at Principia.17

Haru’s reminiscence points to some gaps in the education that Boynton provided. She valued a global perspective and sought to instill it, though at times without enough regard for the significance of her students’ Japanese heritage.18 At the same time, by keeping them informed about world affairs and encouraging them to read The Christian Science Monitor, she helped set the stage for success in their pursuits. As an example, Takashi Oka, who lives in New York today, used a mastery of French, which he learned under Boynton’s tutelage, as a journalist for The Christian Science Monitor, covering the early days of the Vietnam War.19 His unpublished memoir recalls, “My interest in journalism and contemporary political affairs grew out of Miss Boynton’s teaching and her ability to make current events, whether political or cultural, fascinating and alive.”20 While he was still an undergraduate university student in Japan, his English was strong enough that he was chosen as one of six interpreters in the International War Crimes Trial.21

Boynton served as the Committee on Publication in Japan for The Mother Church from 1930 to 1940. This role kept her vigilant about the way Christian Science was portrayed publicly.

Sometime around 1940 the United States government advised Boynton to leave Japan, which had already been at war for two years.22 She complied, never to return. Not long after the country she had come to know so well attacked Pearl Harbor, she passed away on April 7, 1942. Her devotion to teaching and nurturing her students remains a vital piece in the historical record of the global Christian Science movement.

For more discussion about the history of Christian Science in Japan, listen to a related Seekers and Scholars podcast episode, “The Matsukata women—enlightening Japanese-American relations.”

This article is also available in Japanese as a PDF.

Related story: Anna Mallory and Christian Science in Yokohama

“Until reaching Honolulu we did not know that Christian Science had found a permanent foothold in Japan, and so we had a happy surprise when we arrived at Yokohama, and found the Lesson-Sermon was being read each week by a small gathering.” So wrote serviceman K. D. Grant in an October 1908 letter to Mary Baker Eddy, speaking of the group in Yokohama, Japan, that eventually was recognized as a Christian Science Society.1 The Christian Science Sentinel later gave a little history: “Yokohama Christian Scientists began to meet in the home of one of their group Easter Sunday, 1907. As the number of attendants increased, it became possible, in 1919, to organize Christian Science Society, Yokohama.”2

Anna Mallory (1857–1948) of Yokohama was an American woman and one of the earliest Christian Science practitioners in Japan.3 While her work there was likely confined mostly to Europeans and Americans interested in Christian Science, she clearly came to love her adopted country. She lived in Japan from about 1910 until 1943, when forced to leave in the middle of World War II.

Mallory’s testimony of divine protection during the massive Great Kanto earthquake of 1923 speaks of her trust in God and love for Japan. It was published in the January 19, 1924, issue of Christian Science Sentinel. You can read it here.

On her return to the United States, at the age of 86, Mallory was aboard the Swedish vessel Gripsholm. Chartered as a “repatriation ship,” it enabled exchanges of both military prisoners and civilians. Along with hundreds of Protestant and Catholic missionaries, she sailed through the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic, by way of the Cape of Good Hope. This much longer route was considered safer than crossing the Pacific.4

Shortly after their arrival in the US, The Christian Science Monitor interviewed Mallory and Lula Dewette, a Yokahama resident and founding member of the Christian Science Society there. The article describes their solidly loving response to the challenges facing them, even as it became more and more apparent that they would have to leave their longtime home. You can read the full article here. It includes interesting accounts of how the two women approached difficult wartime experiences. The interviewer concluded, “Both women have only kindly recollections of their long sojourn in Japan.”5

After returning to America, Anna Mallory lived the rest of her life at Pleasant View Home in Concord, New Hampshire, which at that time was a facility for retired workers in the Christian Science movement.

1. “Letters to Our Leader,” Christian Science Sentinel, 9 January 1909, 371-372.

2. “Japan,” in “Extracts from Reports of Christian Science Committees on Publication,” Christian Science Sentinel, 23 May 1936, 749. The Story of Christian Science Wartime Activities 1939-1946 (Boston: The Christian Science Publishing Society, 1947) notes that the society was forced to dissolve by governmental authorities in 1940 (298). It never reopened.

3. The first practitioner was Zenjiro Ikuta (1881–1944) of Tokyo, listed in The Christian Science Journal until 1938. Little is known of him; census records indicate he was a longtime US resident before returning to Japan in the 1920s.

4. For more information on the voyage, see “1,440 on Gripsholm Wildly Happy Here: Reticent on Trials,” The New York Times, 2 December 1943, 1, 18.

5. Barbara E. Scott Fisher, “Two Repatriated Americans Can Look Back With Pleasure at Long Sojourn in Japan,” The Christian Science Monitor, 7 December 1943, 13.

- ; Emi Abiko, A Precious Legacy: Christian Science Comes to Japan (Boston: E.D. Abbott Co., 1978), 49.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 49-50.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 38-39.

- ”The Lectures,” Christian Science Sentinel, 12 June 1926, 812, https://sentinel.christianscience.com/shared/view/2g0ajv5gly6?s=t.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 22–23, 41.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 41.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 26–27, 50–51.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 42.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 47.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 49.

- Virginia S. Anami, Nishimachi: Crossroads of Culture: A Historical Sketch of Nishimachi International School (Tokyo: Nishimachi International School, 1982).

- Haru Matsukata Reischauer, Samurai and Silk: A Japanese and American Heritage (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 1986), 3.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 51.

- Reischauer, Samurai and Silk, 4.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 57.

- Reischauer, Samurai and Silk, 4.

- Reischauer, Samurai and Silk, 7.

- Reischauer, Samurai and Silk, 7.

- Takashi Oka, “Her lessons shape me still,” The Christian Science Monitor, 10 January 2001, 22.

- Takashi Oka, ”The Memoirs of Takashi Oka,” Unpublished manuscript, 52.

- “Six Interpreters Chosen News Article,” The International Military Tribunal for the Far East, U.Va., 14 November 2015, http://imtfe.law.virginia.edu/collections/phelps-collection/1/1/six-interpreters-chosen-news-article.

- Oka, “Her lessons shape me still,” 22.