Women of History: Miyo Matsukata

Shokuma and Miyo Matsukata. Courtesy of Kaneichiro Imai and Michiko Im

Miyo Matsukata (1891–1984) was one of the first Japanese Christian Scientists. Dedicated to shepherding a newfound religion in an adopted country, she drew on her faith and unique cross-cultural background, challenging opposition to Western religion and the difficulties of World War II.

Born in New York City to Japanese parents, she and her older brother were among the first nisei (second-generation Japanese) on the United States East Coast. Her American childhood was punctuated by summers spent with her grandparents in Japan. At the age of 21, she moved there and married Shokuma Matsukata, the son of a prominent Japanese politician.1 Acclimating to a new culture was difficult for her, and she struggled with the traditions and customs of Japanese life, to the point that her health was affected.2

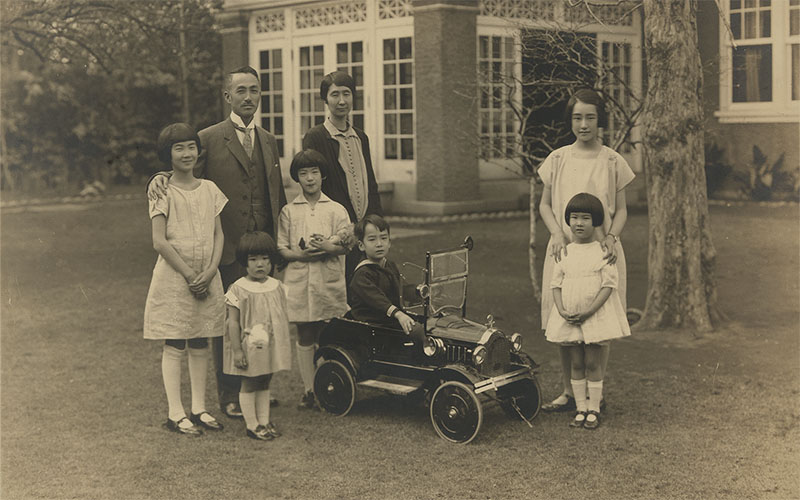

The Matsukata family, circa 1927. Courtesy of Miye Matsukata Estate via Mimi Oka.

In 1917, when the practice of Christian Science was mostly limited to westerners, Matsukata accompanied a friend to a Christian Science lecture, given by Clarence Chadwick in Yokohama.3 4 5 “What hope and joy awakened in me,” she wrote, “when I realized that Christian Science had a divine Principle.”6 As a result she began her own study of Christian Science. At that same time two other Japanese women—Sute Mitsui and Tatsuo Takaki—also learned about Christian Science individually. All three became committed to the faith, despite the fact that it “challenged many rigid customs” and that its practice in this period “required courage as well as tact, patience, wisdom, and love.”7 They turned to Florence E. Boynton, a Christian Scientist schoolteacher from America, to help them and their children in their study.8 According to Matsukata, Boynton “did much to prepare the soil, to sow good seed, and then to care for the growth of that seed.”9

About 1924, Matsukata and her husband hosted Frances Thurber Seal, a visitor to Japan who had earlier helped introduce Christian Science in Germany. Through Seal, she learned about schools for Christian Scientists in the United States (The Principia, in Missouri, and Principia College, in Illinois). Eventually all of Boynton’s young students, including Matsukata’s children, went to study at these institutions.10

Christian Science was spreading slowly in Japan, gaining strength through the efforts of various interconnected Japanese families. The first informal group of Christian Scientists began meeting in 1924. The Mother Church in Boston (The First Church of Christ, Scientist) recognized them in 1931 as Christian Science Society, Tokyo.11 Cultural and linguistic factors made the translation of many terms into Japanese difficult, and at that time people could only study Christian Science in English. That limited its growth, since the general population did not speak English and was unfamiliar with Christianity.12 Matsukata credited her New England education and exposure to Puritan ideas with an ability to understand Mary Baker Eddy’s discovery and accomplishments.13

However, the greatest challenge to this emerging Japanese group came during World War II. Before the United States entered the war, Japan began limiting Western influences and activities. The Society in Tokyo disbanded in 1941, anticipating a law requiring all Christian denominations to unite under the “Christian Church of Japan.” While westerners like Florence Boynton returned to their home countries, Christian Science services continued secretly at Matsukata’s home until the April 1942 bombing of Tokyo.14

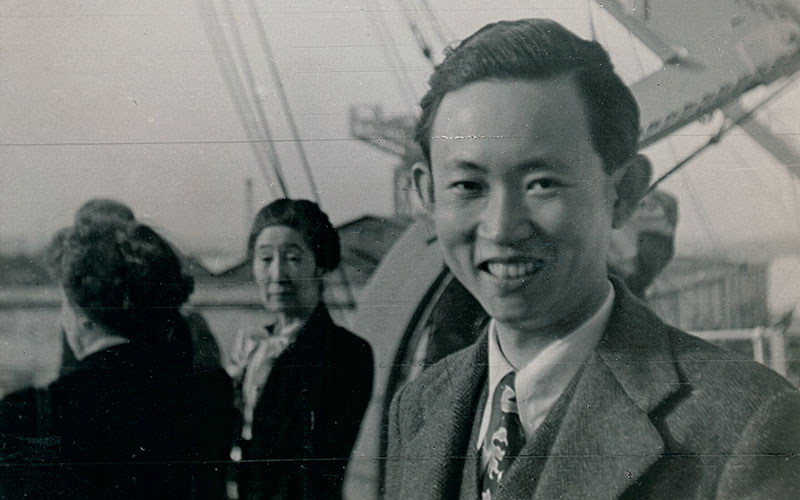

Takashi Oka, circa 1940s. Courtesy of Mimi Oka and Takashi Oka.

A period of isolation followed, in which many Japanese Christian Scientists felt cut off from the world and in particular from The Mother Church. Matsukata initially felt that estrangement. But she later wrote that, when reading “Being is Unfoldment”—an article by Mary Sands Lee in the January 1941 Christian Science Journal—she was struck by the statement that “divine progress is universal as well as individual.” Matsukata later noted this reminded her that “nothing could separate me from divine Love”15 and that it helped her renew a feeling of connection throughout the war. Takashi Oka, who became a correspondent for The Christian Science Monitor, was a Sunday School student in Tokyo when the war began. He later remembered Matsukata as having a strong sense of unity with The Mother Church. She was able to help bridge feelings of separation for other Japanese Christian Scientists by secretly collecting Christian Science literature, mailed under diplomatic protection from Swedish friends to Widar Bagge, the Swedish Minister, who lived next door to the Matsukatas.16

The war’s end in 1945 brought Japanese Christian Scientists renewed contact with the outside world. Mothers like Matsukata, whose children had remained in the United States at Principia College, were able to communicate with them for the first time in four years. Western Christian Scientists arrived as members of the occupation forces, military chaplains, Monitor correspondents, and volunteer workers. Once again people in Japan could openly practice Christian Science alongside new friends, with a variety of experiences to share.17 Matsukata’s family hosted a 1945 Christmas party that author Emi Abiko called “the first bright spot in the otherwise dismal environment.”18

Japanese and American Christian Scientists, Christmas Day 1945. Courtesy of Mimi Oka and Takashi Oka.

Matsukata published a testimony in the June 1969 Journal, noting the benefits of Christian Science to her children. Referring specifically to times of sickness, she wrote that “each case was effectively healed and always gave us a better understanding of the Christ-healing.”19 She was one of the first Japanese Christian Scientists to list her healing practice in the Journal, which she carried from 1947 until her death in 1984.20 During those years she saw her religion grow in Japan beyond its insular beginnings. That included publication of the first Japanese edition of The Herald of Christian Science magazine in 1962, as well as the 1976 Japanese translation of Mary Baker Eddy’s Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures—particularly significant in enabling Japanese-speaking students of Christian Science to study its textbook in their native language for the first time.

Matsukata and her fellow workers laid the groundwork for those and other milestones. In the words of Emi Abiko, they left a “precious legacy to the future generations.”21

For more discussion about the Matsukata family and the history of Christian Science in Japan, listen to a related Seekers and Scholars podcast episode, “The Matsukata women—enlightening Japanese-American relations.”

This article is also available in Japanese as a PDF.

- Haru Matsukata Reischauer, Samurai and Silk: A Japanese and American Heritage (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 1986), 245, 250–251.

- Miyo Matsukata, “History of the Church Universal as Unfolded in Tokyo, Japan,” 7, Church Archives, Box 42561 Folder 285752.

- Emi Abiko, A Precious Legacy: Christian Science Comes to Japan (Boston: E.D. Abbott Company, 1978), 14-15.

- Matsukata, “History of the Church Universal,” 7

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 14, 23.

- Matsukata, ”History of the Church Universal,” 7

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 10-11, 16.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 17, 40.

- Matsukata, “History of the Church Universal,” 4–6.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 29.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 22–23.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 24, 102-104.

- Miyo Matsukata, “In the Christian Science textbook…”, The Christian Science Journal, June 1969, 321.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 69–71.

- Matsukata, “History of the Church Universal,” 14–15.

- Takashi Oka, “The power of love for church in wartime,” The Christian Science Journal, May 2003, 10.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 85–87.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 89.

- Matsukata, “In the Christian Science textbook…”, 321.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 14.

- Abiko, A Precious Legacy, 117.