Women of History: Helen Paul

Helen Paul passport photo, issued July 30, 1930. Courtesy Alice Paul Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, folder 148.

Helen Paul (1889–1961) made significant contributions to the cause of women’s rights. Much of her work involved supporting the work of her older sister, the suffragist Alice Paul (1885–1977). While it has been said that Helen lived in the shadow of her famous sister, her many accomplishments are noteworthy in their own right. Above all, she based her life on a firm commitment to Christian Science.

She was born in Mount Laurel Township, New Jersey, on August 10, 1889. Her parents, William Paul and Tacie Parry, were Hicksite Quakers, who imbued their four children with the ideals of egalitarianism. This included education, in which the Paul sisters enjoyed the same opportunities as their two brothers.1 In 1869 their maternal grandfather had helped found Swarthmore College, “to offer equal opportunities to men and women in education.”2

After her freshman year, Helen transferred from Swarthmore to Wellesley College, where she was active in the school’s Philosophy Club, serving as president her senior year. She was also an enthusiastic member of the Agora Society, a political organization. In a letter to her mother, she announced:

Today I received an invitation to join Agora . . . . It is the one which has for its aim & work, the study of current events and the furthering of a Democratic spirit, the girls are perfectly splendid, I can scarcely believe that they have asked little me. Miss Calkins [Mary Whiton Calkins], the philosophy instructor, and both the heads of the Economics department are faculty members….3

Helen Paul in the driver’s seat of the Paul family’s Cadillac. Her mother, Tacie Paul, is seated in the back. c. 1912. Courtesy Alice Paul Institute.

After earning her bachelor’s degree from Wellesley in 1911, she obtained a scholarship from the University of Pennsylvania to pursue graduate study in Chinese. Her vision was to engage in missionary activities in China.4 However it was around this time that her life took an unplanned turn, when she became deeply interested in Christian Science.

1916 was a watershed year for the Paul sisters. In June Alice spearheaded the formation of the National Woman’s Party, to intensify political pressure to bring about an amendment to the United States Constitution to guarantee a woman’s right to the vote. And Helen departed from generations of her forebears by resigning from the Quaker religious community to become a Christian Scientist, prompted by a healing she experienced through Christian Science.5 She officially joined The First Church of Christ, Scientist, that November.6 This would lead to her helping to found a Christian Science church in the Quaker village of Moorestown, New Jersey, where she then lived.7 Alice remembered her sister as “sort of the soul of this little church, though she was very young.”8

Even before this, Helen had championed and supported her sister’s campaigns to advance women’s rights. She served at various times as her secretary, and in other roles in the National Woman’s Party and the World Woman’s Party, which Alice founded.9

While Alice placed herself on the front lines of protest, Helen worked hard behind the scenes, helping to organize suffrage campaigns. She “enthusiastically joined suffrage activities” after Alice became involved with the Pankhursts, a family of British suffragists, and later rose to leadership in the American suffrage community. Helen helped organize the New Jersey contingent for the March 1913 suffrage procession in Washington.10

Paul family photograph: Helen Paul standing in the front row next to her sister, Alice, whose hands are folded in front of her. 1910. Courtesy Alice Paul Institute.

Alice applied some of the more militant tactics she had experienced with the Pankhursts in England. This caused tensions within the US suffrage movement, as well as concern to Helen and other members of the Paul family. Still, Helen’s loyalties to Alice and the cause of women’s rights remained strong throughout her life, even after the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified in 1920, with its guarantee of universal suffrage. At the same time, Helen’s dedication to the study and application of Christian Science teachings deepened. Loyalty to family and to her sister’s political initiatives operated in parallel with her spiritual convictions. Her adoption of Christian Science stemmed from more than an intellectual interest; it satisfied a search for meaning and purpose, and brought freedom from mental anguish. She described that journey in a 1919 testimony of healing, published in the Christian Science Sentinel:

… For many years I longed to know what we were and what life meant. A search of college philosophy courses brought no solution. Mental and moral blindness finally resulted in a nervous breakdown, accompanied by severe headaches and a fear of losing my reason. My work at the university had to be abandoned and relief was sought in rest and osteopathic treatment. The physical conditions seemed to improve, but as the mental distress continued, a visit to a near-by relative was planned. This cousin was a Christian Scientist and told me of her healing of eye trouble. Her poised and happy life struck me as a contrast to mine, and I decided to see a practitioner. At first the explanations given seemed to my egotistical sense like a strange tongue, but I was impressed with the fact that the practitioner really seemed to believe that God heard her prayer and would answer her. In despair I decided to put aside the cynical feeling and cling to the hope held out. I shall never forget my reading of “The New Birth,” in “Miscellaneous Writings,” next morning.11

From that time all has been different. I put off my glasses at once and have never had them on since. The rest that a knowledge of Truth brings after the strain and stress of the previous confusion is like the calm after a storm at sea….12

Even as Helen was increasing her devotion to studying Christian Science and participating in church activities, she supported her sister, whose campaign for women’s suffrage was growing more adamant—and dangerous. In November 1917 she went to Washington, DC, following Alice’s imprisonment for picketing outside the White House. One particular response among some incarcerated suffragists was to go on hunger strikes—a tactic met with force-feeding through the mouth and nose. On November 9, 1917, The New York Times noted that “Alice Paul, Chairman of the National Woman’s Party . . . was forcibly fed at the Asylum Hospital today.” The report also focused on Helen’s concern for her: “Miss Helen Paul came to Washington from Moorestown, N.J., yesterday to remain as close to her sister as the jail authorities permit.” The piece went on to quote Helen:

I told Mr. Zinkham [the prison warden] that he would kill my sister if he forcibly fed her. She has never been able to tell me about her experience in England, it was so horrible, and I know she cannot go through with it again. How can such a brutal thing be thought of when all she is asking is decent treatment for the others imprisoned with her?

“What has she done that she should be treated like a criminal and not even as well, for they are permitted exercise and visitors and can buy food at the jail canteen. She has given her life to working for suffrage for women….13

Soon after, Alice was released from the Asylum Hospital.

Following the enactment of the Nineteenth Amendment, Alice continued her activism on women’s issues.14 For Helen, those years involved pursuing a career in education, while also maintaining political involvement in women’s issues. She qualified as an elementary and secondary school instructor, licensed to teach a wide range of subjects in New Jersey’s public school system.15

Later in her career, after attending sessions of the League of Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, with Alice, she lectured on the work of the League “in the High Schools of South Jersey.”16 She also served for a time as “Legislative Chairman of the New Jersey League of Women Voters.”17 An indication that her interest in education was ongoing, she pursued studies in fine arts, ceramics, and education at Ohio State University.18 This led to her teaching pottery and other skills at schools and camps, including at the Little Red School House, a progressive school in New York City.19

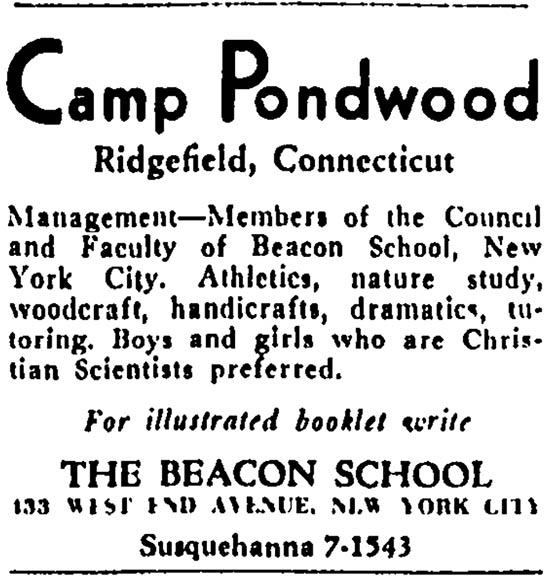

Around 1930 Helen took Christian Science Primary class instruction from Norman John, CSB.2021 That year she also purchased property from him in Ridgefield, Connecticut, and, at his suggestion, established a summer camp there for Christian Scientists. She called it Pondwood.22

Advertisement for Camp Pondwood, The Christian Science Monitor, April 23, 1931

Alice often lived with Helen at her home in Ridgefield. This gave her firsthand knowledge of Helen’s involvement with Christian Science, while at the same time allowing Helen to have a direct hand in her sister’s causes. As feminist historian Leila Rupp has noted, “Helen Paul, through her relationship with Alice, often played a major role in Woman’s Party work.”23

Helen’s understanding of “Woman’s Party Work” found expression in articles she contributed to The Christian Science Monitor. Along with Ernestine Hale Bellamy, an officer in the National Woman’s Party, she co-wrote a piece on the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in July of 1949. Alice was an inaugurator of the proposed amendment, so Helen had firsthand knowledge of its history, and the long road it was traveling in the effort for its adoption into the US Constitution. The article stated:

Following the winning of suffrage in 1920, the National Woman’s Party proposed a second constitutional amendment—to remove every handicap under the law. This amendment was first presented to Congress in 1923, and has been introduced into every Congress since that time. It is known as the Equal Rights Amendment, and reads as follows, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”24

A few months after its publication, the article was entered into the Record of Proceedings and Debates of the 81st Congress of the United States, as evidence in support of legislative efforts for the ERA.25

In correspondence to others in the Woman’s Party, Alice often recognized Helen’s contributions. She drew attention to an article that Helen had written for The Christian Science Monitor on December 15, 1950, titled “The UN Assembly Moves Toward Establishing Substantial Gains for Women,” which noted this:

On December 4, the General Assembly took action of great significance in the history of the worldwide movement to raise the status of women when it adopted a resolution reading: “The General Assembly decides to include economic, social, and cultural rights in the draft Covenant on Human Rights, and an explicit recognition of the equality of men and women, on related rights, as set forth in the Charter of the United Nations.”26

In a 1951 letter to Clara Snell Wolfe, a leader in the National Woman’s Party, Alice enclosed that Monitor account, explaining, “My sister wrote it in an effort to help us get a little publicity on the United Nations work.”27 Members of the National Woman’s Party and the Woman’s World Party recognized Helen’s value to their work and mission. In a letter to Alice, Mary Burt Messer captured this sentiment: “What a treasure is Helen Paul as a lieutenant, with that fine ability to write – that is positively one of your best write-ups. I wrote to the Monitor in appreciation of their handling of it.”28

Correspondence between the sisters makes it clear that Alice appreciated how Helen’s deepest convictions were allied to furthering the cause of Christian Science. In one letter to Alice (using traditional Quaker language) Helen described how she wanted the celebrated artist Violet Oakley—herself a Christian Scientist—to paint Alice’s portrait. Referencing a conversation in which Oakley had shown an enthusiastic willingness to make the painting, she urged, “Thee really must let her [Oakley] do it – beautiful sister. Thee is so lovely – and so beloved and we do want very much for the World Woman’s Party to have a lovely picture of thee.”29

She then went on to discuss her own life and work endeavors. “It is much wiser,” she wrote, “to work with [Christian] Scientists (sic).” Then she explained, referencing Mary Baker Eddy’s writings, “And will be far easier for me – because my work is the establishing of ‘the truth the gospel and the science necessary to the salvation of the world from error, sin, disease and death.’ It is essential to find fertile soil for the work.”30

An examination of Helen Paul’s life and work expands our knowledge and awareness of the influence Christian Science had in arenas involving advancing women’s and human rights. It adds to a growing picture of women for whom Christian Science was central—and who were also activists for feminist and humanitarian causes.

Listen to Women of History from the Mary Baker Eddy Library Archives, a Seekers and Scholars podcast episode featuring Library staffers Steve Graham and Dorothy Rivera.

- Jill D. Zahniser and Amelia R. Fry, Alice Paul: Claiming Power (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 11.

- Katherine J. Adams and Michael L. Keene, Alice Paul and the American Suffrage Campaign (Urbana, Illinois, and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 5.

- Helen Paul to Tacie Paul, 16 March 1909, in Helen Paul: correspondence, from family to Helen, 1903–1947, Alice Paul Papers (APP), Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, MC399, folder 161. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:428015035$92i

- Alice Paul Institute (API), Helen Paul records.

- API, Helen Paul records.

- The First Church of Christ, Scientist, Boston, member records.

- See Adams and Keene, Alice Paul and the American Suffrage Campaign, 3.

- “Conversations with Alice Paul: Woman Suffrage and the Equal Rights Amendment: an interview conducted by Amelia R. Fry” (Berkeley, California: Bancroft Library, Regional Oral History Office, University of California, Berkeley, 1976), 10. http://content.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt6f59n89c&doc.view=entire_text/ accessed 5.19.2021.

- Biographical Note, “Alice Paul,” APP. https://schlesinger.radcliffe.harvard.edu/onlinecollections/paul/learnmore/ accessed 5.21.2021.

- Jill D. Zahniser, Biographical Sketch of Helen Paul. Included in Part I: Militant Women Suffragists—National Woman’s Party, Database assembled and co-edited by Thomas Dublin and Kathryn Sklar (Alexandria, Virginia: Alexander Street Press, 2015). https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/d/1009054755/ accessed 5.24.2021.

- The “New Birth” is an essay by Mary Baker Eddy, first published in The Christian Science Journal in October 1883. It may also be found in Eddy’s Miscellaneous Writings 1883–1896 (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 15–20.

- Helen Paul, testimony, Christian Science Sentinel, 25 October 1919, 157.

- “Hunger Striker Is Forcibly Fed,” The New York Times, 9 November 1917, 13.

- For example, Alice authored the original proposal for the Equal Rights Amendment. She also worked for women’s rights internationally through the League of Nations, which led to her founding of the World Woman’s Party in 1938. After World War II, she continued these efforts through the United Nations.

- See Helen Paul: employment: certification, notes, 1916–1920, 1955, APP, MC399, folder 158. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:451066313$4i.

- Helen Paul entry, Wellesley College, Twentieth Reunion Record, Class of 1911, API, Helen Paul records.

- ibid.

- Helen Paul: education: transcripts and grades, 1934–1958, APP, Personal and Family, MC 399, folder 155. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:428010652$6i

- Helen Paul entry, Wellesley College, Twenty-fifth Reunion Record, Class of 1911, API, Helen Paul records.

- See correspondence to Helen Paul from Students’ Association, Pupils of Norman E. John, C.S.B., APP, Personal and Family, MC399, folder 168. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:428015447$1i

- Class instruction provides students with an opportunity to deepen their understanding and practice of Christian Science healing.

- A Handbook for Summer Camps: Annual Survey, 12th ed. (Boston: Porter Sargent, 1935), 370. https://books.google.com/books?id=55svAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA370&lpg=PA370&dq=Camp+Pondwood;+Helen+Paul&source=bl&ots=As-olmsuGQ&sig=ACfU3U3S_kRhtWHtdiPbvqBM8wGbgDGbkg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwidva7_govxAhXnc98KHZjCCmoQ6AEwEHoECBYQAw#v=onepage&q=Camp%20Pondwood%3B%20Helen%20Paul&f=false. In her oral history with Amelia Fry, Alice Paul gives background on the camp: see “Conversations with Alice Paul: Woman Suffrage and the Equal Rights Amendment: an interview conducted by Amelia R. Fry,” 10. https://oac.cdlib.org/view?docId=kt6f59n89c&doc.view=entire_text/ accessed 5.19.2021.

- Leila J. Rupp, “‘Imagine My Surprise’: Women’s Relationships in Historical Perspective,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Autumn 1980, 65. https://doi.org/10.2307/3346519.

- Helen Paul and Ernestine Hale Bellamy, “Equal Rights Amendment Backers See Influential Groups Lending Support,” The Christian Science Monitor, 7 July 1949, 12.

- See Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 81st Congress, First Session, Appendix, August 25, 1949–October 19, 1949 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1949), A6231-A6232. https://books.google.com/books?id=jL7Ae38ncCkC&pg=SL1-PA6231&lpg=SL1-PA6231&dq=ernestine+hale+bellamy&source=bl&ots=n7REyn3lUf&sig=ACfU3U0CjG3cFTL6TVll6szHtU8QbZCX6Q&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi-4fn2up7xAhURV80KHd4WCP0Q6AEwD3oECBIQAw#v=onepage&q=ernestine%20hale%20bellamy&f=false

- Helen Paul, “UN Assembly Moves Toward Establishing Substantial Gains for Women,” The Christian Science Monitor, 15 December 1950, 14.

- Alice Paul to Clara Snell Wolfe, 6 January 1951, National Woman’s Party Records, World Woman’s Party Papers, 1938–1958, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress .

- Mary Burt Messer to Alice Paul, 21 December 1950, National Woman’s Party Records, World Woman’s Party Papers, 1938-1958, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. .

- Helen Paul to Alice Paul, n.d., APP, Personal and Family, Correspondence: Helen to Alice, 1942-1954, MC399, folder 32. https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:426994353$19i

- Ibid. Helen Paul references Mary Baker Eddy, Miscellaneous Writings 1883–1896 (Boston: The Christian Science Board of Directors), 177, where Eddy asks of her followers, “Will you give yourselves wholly and irrevocably to the great work of establishing the truth, the gospel, and the Science which are necessary to the salvation of the world from error, sin, disease, and death?”