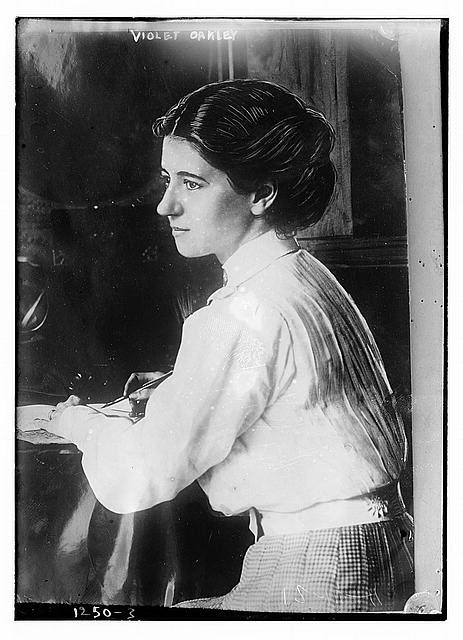

Women of History: Violet Oakley

Portrait of Violet Oakley, 1900. Photo by Bain News Service.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-B2-1250-3.

My own faith in an organized world governed by international law dates from my first study of the life of William Penn and his ‘Holy Experiment,’ as he called the unfortified Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1682.

—Violet Oakley

Violet Oakley (1874-1961) is now widely known for her talents as an illustrator, stained glass designer, manuscript illuminator, portrait painter, author, and speaker. This remarkable woman gained prominence as an artist at a time when women’s artwork was generally considered inferior to that of men. She worked for the recognition of women in male-dominated institutions in the arts and literature.

Oakley was a prolific illustrator. Her images, appearing in prominent magazines, helped promote women as confident and educated. But perhaps her most widely known accomplishments are as a muralist; she was the first American woman to receive a public mural commission and proved that a woman could not only succeed but create masterpieces in a medium dominated by men. Grand themes of the quest for peace and freedom, undergirded by vigilance and diligence—two qualities she greatly valued in humanity’s quest for peace—resonate through her works, which take on a number of different styles, including Pre-Raphaelite and Art Deco.

Born June 10, 1874 in Jersey City, New Jersey, Violet came from a family of artists, including both her grandfathers. When she was 21, the family traveled to France, where she was inspired by her exposure to works of the great Impressionists. She attended the Académie Montparnasse, studying with the painters Raphaël Collin and Edmond Aman-Jean. When her family returned to America, she studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, the city that would remain her home for the rest of her life. It was after her sister Hester began studying illustration at the Drexel Institute, and urged Violet to join her, that Oakley became a student of famed illustrator Howard Pyle, who recognized her talent. Under his instruction she blossomed.

In 1902 architect Joseph M. Huston chose Oakley to decorate the new Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg, “purely because of her immense talent.” Oakley invested a great deal of time researching for the assignment, traveling to Europe and delving extensively into the life of William Penn, who features prominently in her painting for the Governor’s Reception Room, The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual. In the years that followed, she was commissioned to paint murals for the Capitol Rotunda and for the Senate and Supreme Court chambers. In all, 43 of Oakley’s murals adorn the walls of state buildings in Harrisburg; they were painted over the course of 25 years.

Penn’s Vision by Violet Oakley (oil paint over printed base) adorns the Governor’s Reception Room at the Pennsylvania State Capitol.

The murals can be viewed as a testimony to Oakley’s moral and spiritual ideals. Raised an Episcopalian, Oakley embraced Quakerism and its advocacy of equality and pacifism—two major themes in her artwork. She particularly admired William Penn’s utopian vision for his Pennsylvania commonwealth. Then, about the time she received the State Capitol commission, she found a stronger validation of her own ideals in the teachings of Christian Science, which Mary Baker Eddy had brought to prominence during the time Oakley was growing into adulthood. It’s likely that these words of Eddy in Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures especially resonated with her: “Civil law establishes very unfair differences between the rights of the two sexes. Christian Science furnishes no precedent for such injustice, and civilization mitigates it in some measure. Still, it is a marvel why usage should accord woman less rights than does either Christian Science or civilization” (p. 63).

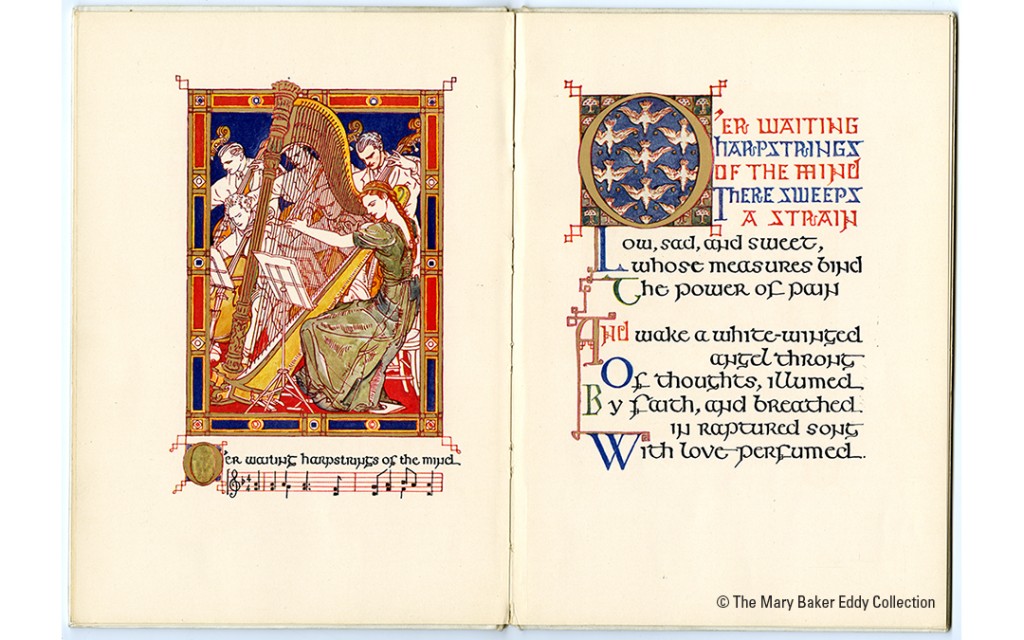

Certainly the prospect of a cure for her lifelong bouts of asthma attracted Oakley to study Christian Science, and she credited it with her healing of that disease. After a childhood and youth marked by illness and excessive sheltering by her parents, she now enjoyed freedom and strength. She remained a Christian Scientist for the rest of her life, taking Christian Science class instruction and attending Second Church of Christ, Scientist, in Philadelphia from the time it opened in 1912. Her illustrations for Mary Baker Eddy’s poem “Christ My Refuge,” published in 1939, vividly depict its message of uplift and illumination.

Oakley was a prolific artist, and it is said that she worked up to the last day of her life. At age 81 she led a large group from Philadelphia on a tour of her work in Harrisburg. She was politically active, supporting the League of Nations, the United Nations, and Cold War nuclear disarmament. She is also known as one of the “Red Rose Girls,” who along with fellow artists Elizabeth Shippen Green and Jessie Willcox Smith transformed the Red Rose Inn on Philadelphia’s Main Line into a communal art gallery, where the women lived and worked together—something quite revolutionary that pushed against the strict gender roles of the time. She was instrumental in establishing The Plastic Club in Philadelphia (to promote “art for art’s sake”), as well as the Philadelphia Art Alliance.

Violet Oakley died in Philadelphia on February 25, 1961. During much of her lifetime, she was considered the most distinguished woman painter in the United States. But her name fell into relative obscurity after World War II. By the early 1970s, however, there was an increased interest in the artistic styles she championed, and that has led to a deeper interest in her works and those of her colleagues. In 1977 Oakley’s studio in Philadelphia was listed in the National Register of Historic Places, as recognition for her multifaceted genius.

Listen to “Religious tolerance and the art of Violet Oakley”— a Seekers and Scholars podcast episode featuring Dr. Patricia Likos Ricci, a leading Oakley scholar.